Ranking violent conflict levels across the world

Mid-Year Update: Data as of July 2023

1 in 6 people

are estimated to have been exposed to conflict so far in 2023

i

A population is classed as exposed if it is within 5km of a political violence event

50 countries

rank in the Index categories for extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict

i

All countries receive an Index score and 50 meet the top three categories

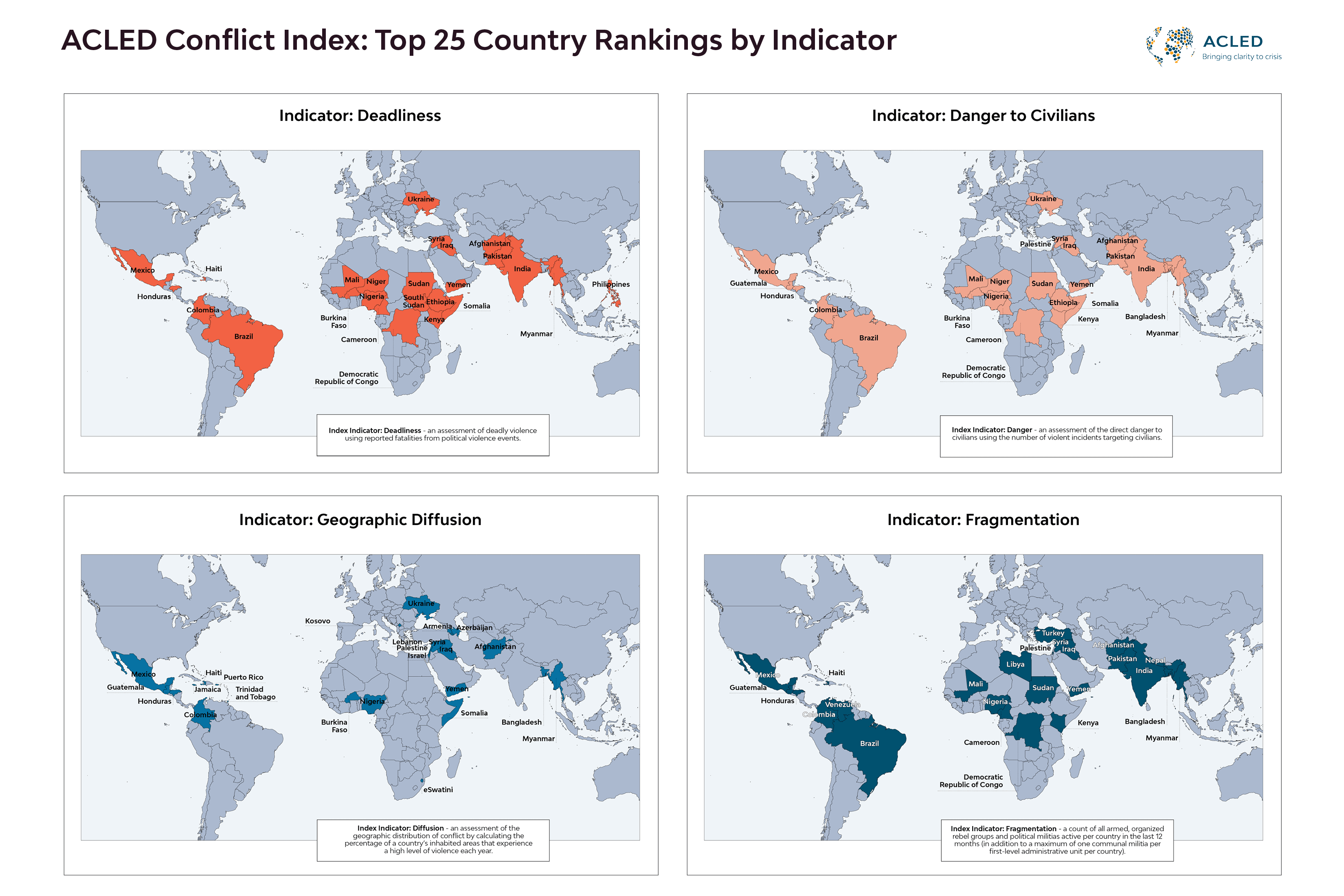

Ukraine, Myanmar, Mexico, and Palestine

top each of the Index’s four indicators

i

27% increase

in political violence incidents recorded in past 12 months

i

Total number of political violence events in July 2022-June 2023, compared to July 2021-June 2022.

Methodology

- About

- Indicators

- Definitions & Data Sources

- Rankings

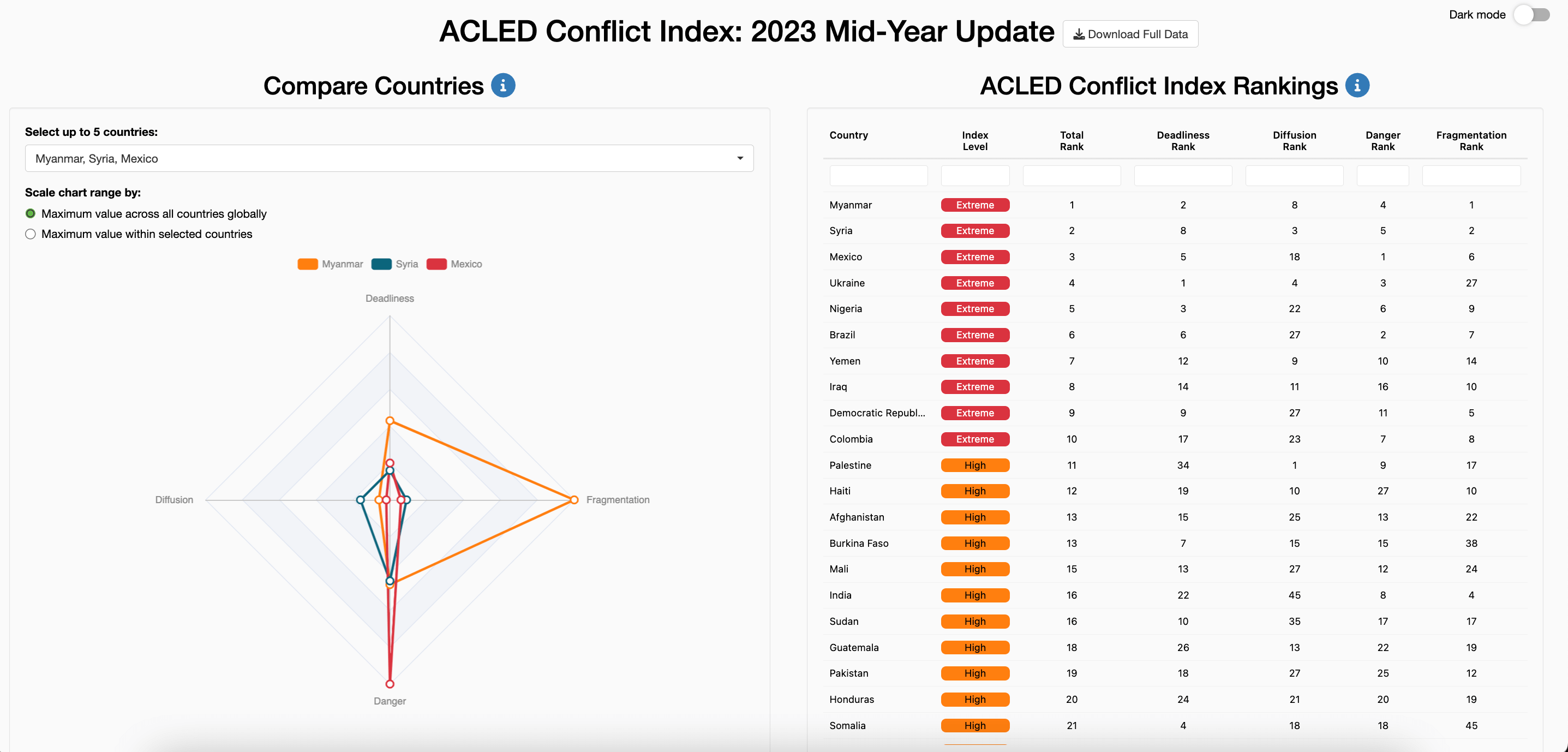

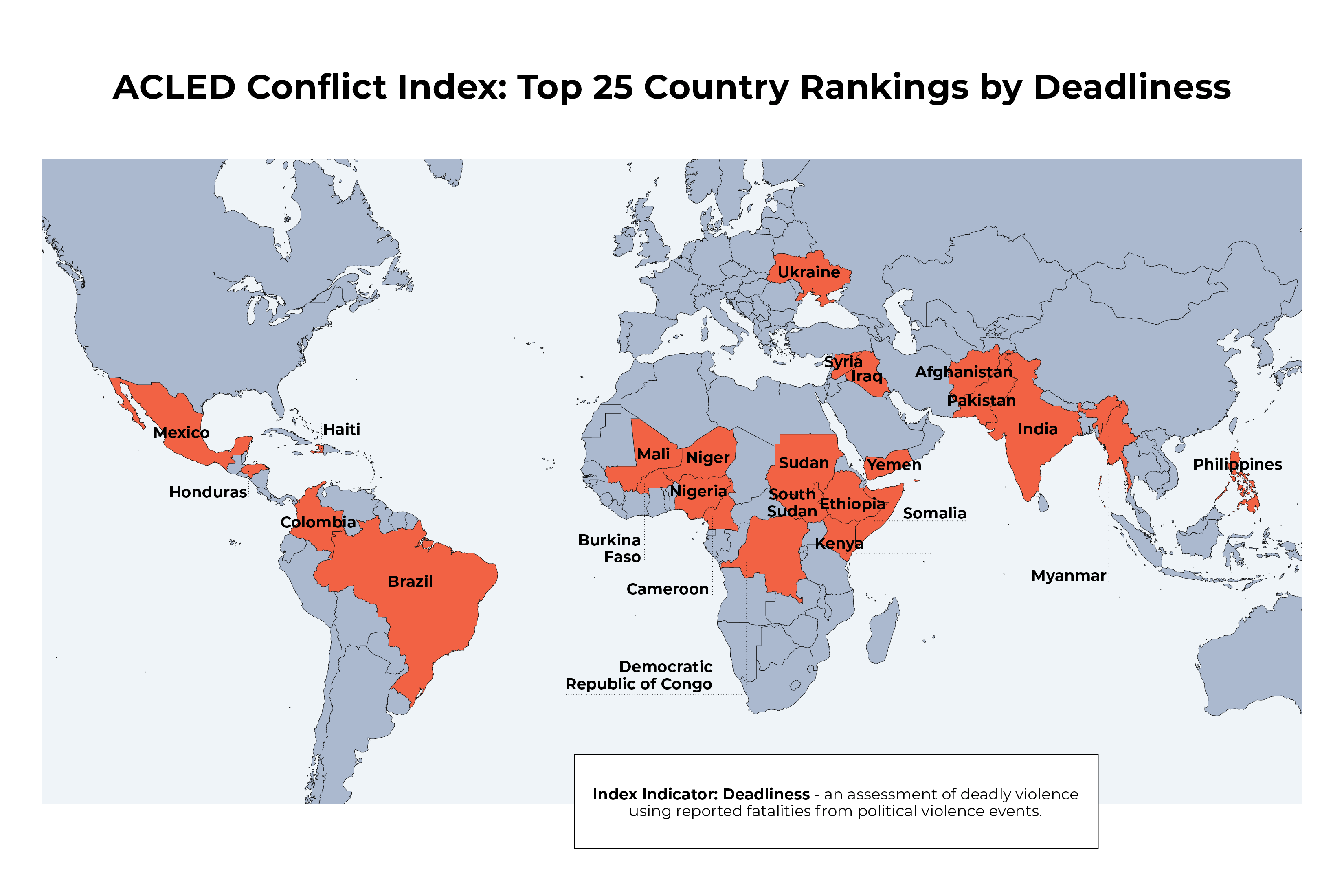

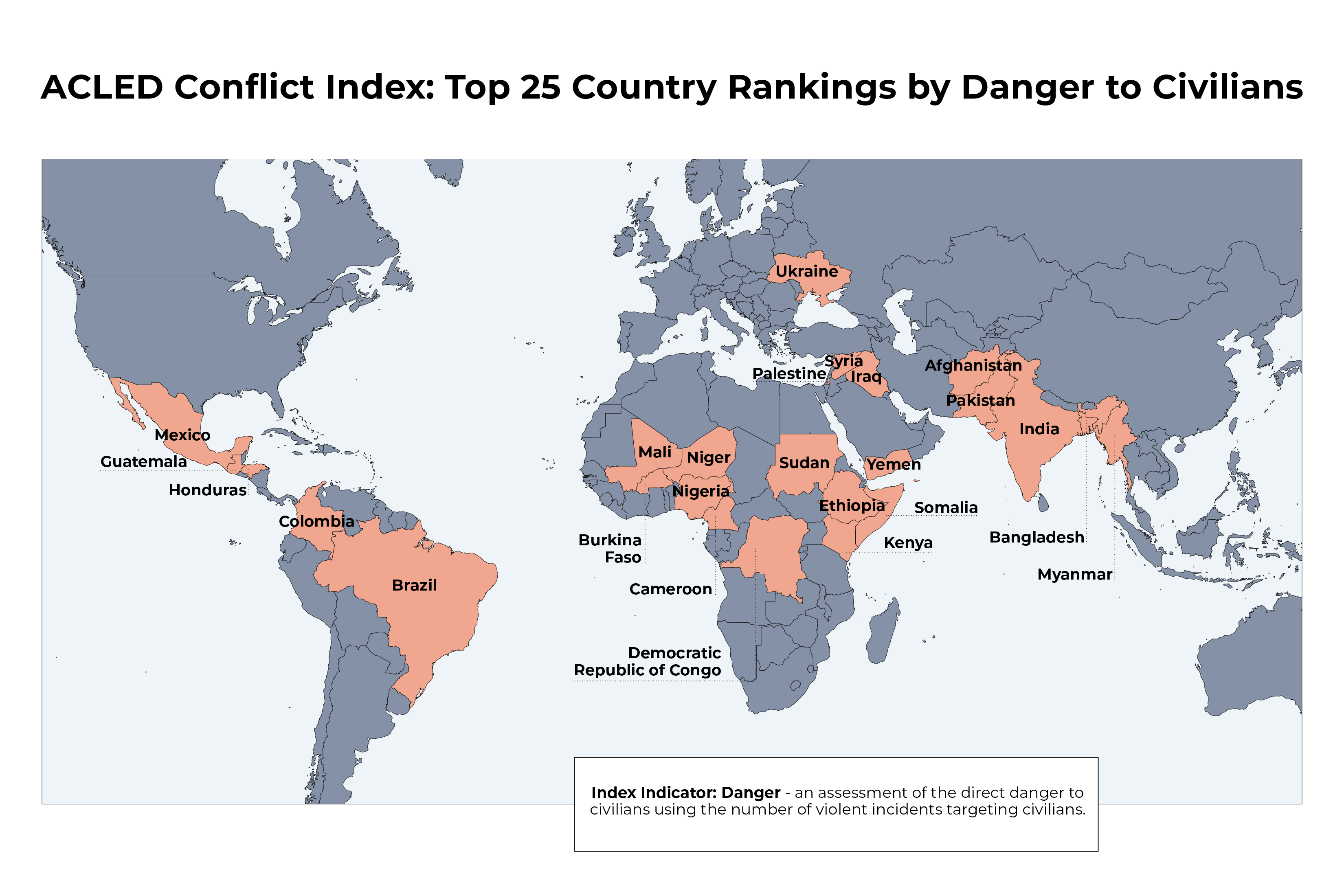

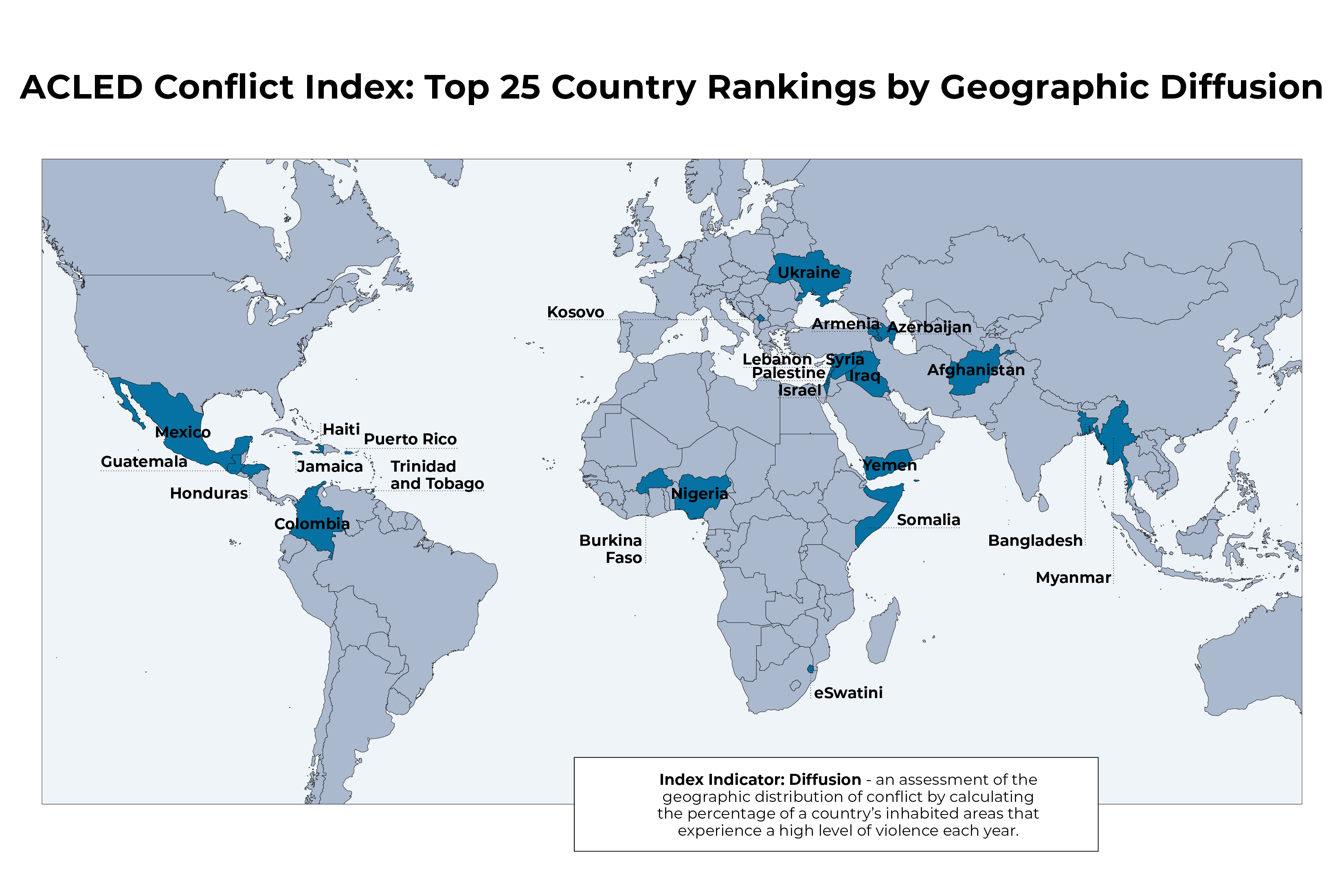

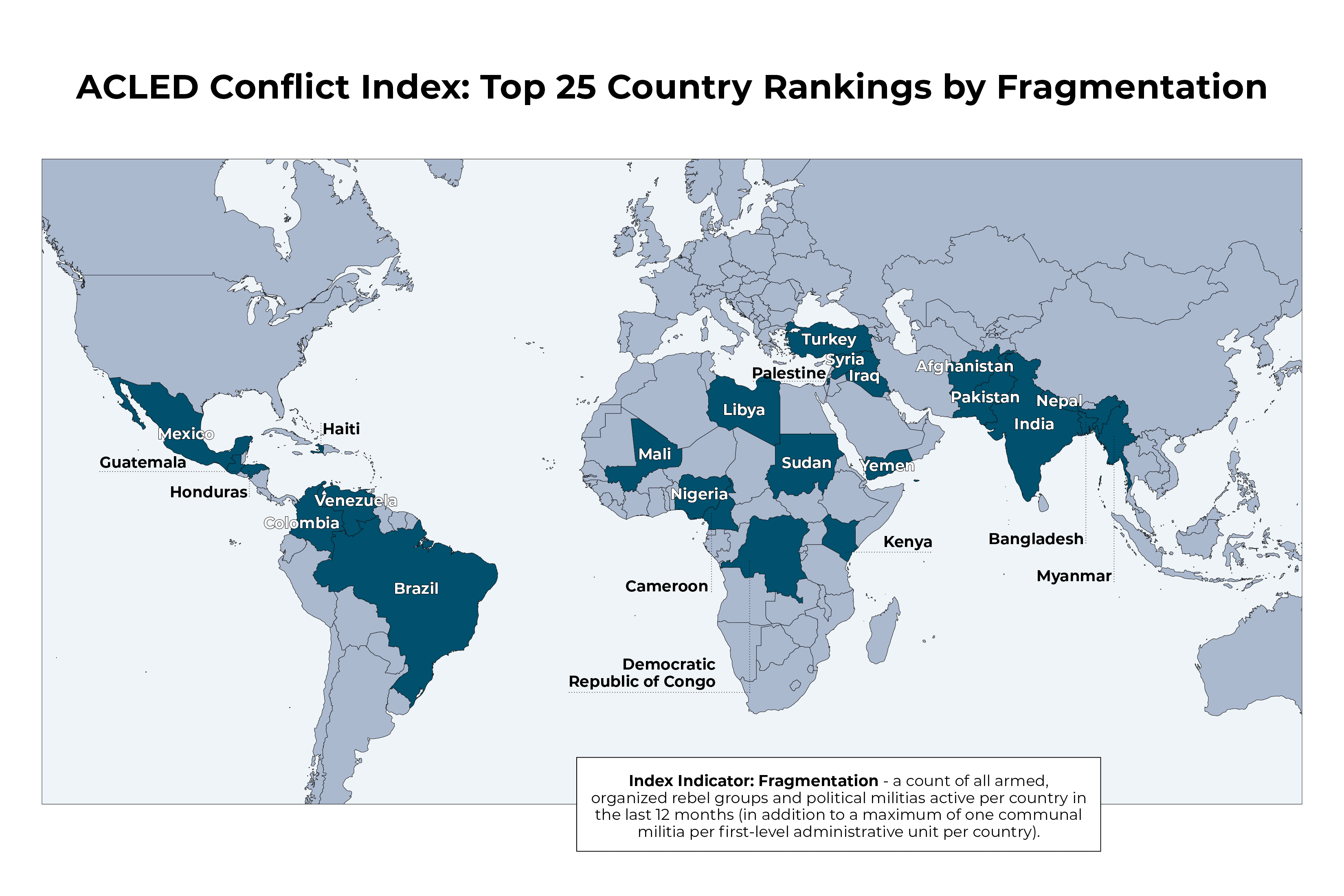

The ACLED Conflict Index uses four indicators to measure conflict levels: Deadliness, Danger, Diffusion, and Fragmentation. The values for each indicator are calculated for each country or territory, scaled, and ranked. The top ranked countries overall are experiencing the most severe, complex, and difficult-to-resolve conflicts.

Countries often host multiple discrete conflicts, which can be an accumulation of actions by several armed groups. These groups often have differing political aims, trajectories, and life spans. The Index accounts for all conflicts occurring within countries by examining their combined incidents of violence.

Countries with high incident totals or high conflict fatalities are highly violent and deadly. But incident and fatality counts when evaluated on their own – isolated from aggravating factors and local context – can often distort the size and impact of conflict for different communities and governments. Further, conflicts that have similar rates of intensity are rarely similar in other ways. In Haiti and the Philippines, for example, the conflict event rate is consistent (close to 700 political violence events per year), but the violence impacts their respective communities and governments in very different ways. Conflicts can also differ with respect to the risks faced by different communities. For example, a civilian in Mexico is currently twice as likely to be killed by political violence as a civilian in Syria.

The ACLED Conflict Index is designed to first distinguish conflict risk factors by deadliness, danger, diffusion, and fragmentation, and then to create a relative country ranking based on the combined intensity of risks.

The first version of the Index was launched in January 2023, and an expanded version based on an updated methodology was released in September 2023.

All countries and territories are assessed according to each indicator. Countries are then ranked by their scores for each indicator.

| Indicator | Measure | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Deadliness | How fatal are political violence events? |

The amount of political violence-related fatalities can indicate

how intense conflict is within a state. The Deadliness indicator represents the number of reported fatalities per country in the 12 months preceding the latest update of the Index (e.g. July 2022-July 2023 for the mid-year Index update). |

| Danger | How many political violence events are targeted towards civilians? |

Conflicts differ with respect to how much armed groups —

including state actors – prey on civilians. Conflicts that have

a higher rate of civilian violence are likely to continue and

proliferate, in part because armed groups are not facing more

active resistance from other armed entities. The Danger indicator represents the number of violent events targeting civilians per country in the 12 months preceding the latest Index update. |

| Diffusion | What proportion of the country experiences a high level of violence? |

Many conflicts can occur in a country simultaneously, adding to

the geographic spread of conflict across states. This measure is

an assessment of the geographic distribution of conflict. Each

country is divided into a 10km-by-10km spatial grid. Grid cells

that have a population of fewer than 100 people are excluded.

Next, ACLED determines how many of a country’s geographic grid

cells experience a high level of violence, defined as at least

10 events per year (representing the top 10% of cases).

The Diffusion indicator represents the proportion of high violence grid cells to total cells (i.e. the percentage of geographic area experiencing high levels of violence) |

| Fragmentation | How many non-state armed, organized groups are operating within the conflict? |

The fragmentation of a conflict environment indicates the number

of distinct threats and agendas that are accumulating in a given

context and posing harm to communities and state institutions.

It also indicates the number of distinct political motives and

opportunities to form an armed group. A singular consolidated

armed group can be a serious challenge to governments, but it

can also take part in effective negotiations and engagements. A

highly fragmented environment, in contrast, makes it more

difficult to engage the necessary actors in effective

negotiations and may indicate multiple overlapping conflicts

that are more challenging to simultaneously resolve. The Fragmentation indicator is a count of all armed, organized, active rebel and political militias per country in the last 12 months (excluding unidentified armed groups and including pro-government militias). In addition, a maximum of one communal militia is counted per first level administrative unit per country. |

Definitions

In alphabetical order:

Cartels: Organized armed groups that do not seek to topple the state, but rather seek to control territory for the purpose of extracting exclusive economic benefits via illicit activities.1Lessing, B. (2015). "Logics of Violence in Criminal War." Journal of Conflict Resolution 59.8: 1486-1516. Examples include the Sinaloa cartel in Mexico.

Event: The fundamental unit of observation in ACLED is referred to as the “event.” Each coded event involves at least one designated actor – e.g. a named rebel group (or, in some cases, an unidentified group), the type of action carried out, a specific named location, a specific date, and other key variables. ACLED currently codes for six event types and 25 sub-event types, both violent and non-violent, that enable analysis of patterns of political violence and demonstration activity.

Executions/Assassinations: The killing of ruling elites, prominent members of society, or important political figures and dissidents. Examples include the assassination of political elites in Yemen and the assassinations of social leaders in Colombia during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fatalities: In ACLED analysis, the use of the term fatalities always refers to reported fatalities recorded in the dataset, per ACLED fatality methodology.

Gangs: Organized criminal groups whose violent actions (e.g. battles and varied violence against civilians) can have clear political consequences despite a lack of an overt political agenda. They commonly cooperate with local elites and participate in income-seeking behavior, but vary in the degree to which they are organized and at what scale they operate. Examples include the Red Command in Brazil.

Gang Violence: Violence committed by criminal groups without an overt political agenda, also known as gangs (see above). Gang violence is only captured in the ACLED dataset in certain circumstances that have been determined to meet the parameters for inclusion based on the country-context, as outlined in the ACLED methodology brief, Gang Violence: Concepts, Benchmarks, and Coding Rules.

Insurgency: This term refers descriptively to violent activity carried out by an organized, armed, non-state group or groups internally against a governing authority, often to contest control over a territorial area. Use of the term is highly context-specific, and the aims, ideology, intensity, size, and geographic scope of insurgencies will vary.

Militias: The ACLED dataset categorizes two types of militia, political militias and identity militias, and acknowledges the actions of pro-government militias.

- Political Militias: Armed, organized groups with political goals that use violence to advance those goals. Unlike rebel groups, political militias generally do not actively seek to topple or replace the national government using violence, though some are organized in opposition to government authority (e.g. anti-government militias in the United States that at times shift orientation based on the dominant national party or president). These groups often cooperate or ally with various domestic elites as well as external forces, albeit typically without a formal link. Examples include Loyalist militias in Northern Ireland, far-right militias and militant social movements in the United States (such as the Three Percenters or the Proud Boys), and the Bakassi Boys in Nigeria.

- Identity Militias: Armed and violent groups organized around a collective, common feature including community, ethnicity, region, religion, or, in exceptional cases, livelihood. Therefore, identity militias captured in the ACLED dataset include those reported as tribal, clan, communal, ethnic, local, community, religious, and livelihood militias. Violent events involving identity militias are often referred to as communal violence, as these violent groups frequently act locally, in the pursuit of local goals, resources, power, security, and retribution. An armed group claiming to operate on behalf of a larger identity community may be associated with that community, but not represent it (e.g. Luo Ethnic Militia in Kenya or Fulani Ethnic Militia in Nigeria). Recruitment and participation are by association with the identity of the group. For more, see ACLED Codebook section on Actors.

Mob Violence/Vigilantism: Extrajudicial violence in response to crimes, real, perceived, or not yet committed.2Bateson, R. (2021). "The Politics of Vigilantism." Comparative Political Studies 54.6: 923-955. This can also include the use of violence to punish social infractions or deviations from social norms. Examples include lynchings in Port au Prince, Haiti, or South Africa, as well as pandemic-related attacks against healthcare workers in India.

Organized Criminal Violence: Organized crime is the use of violence by highly organized groups in order to control (often illegal) markets and extract economic benefits. Resources that can motivate such violence can include timber, drugs, diamonds, minerals, and more. The designation of violence of this form is not based on the size of the organization or their scope. Organized violence can be localized but networked over larger spaces - such as the Mafia violence of Southern Italy;or specifically relating to a locality or entire region, such as the various agents and groups engaged in the Mexican drug war.

Political Violence: The use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation. In analysis, this is a category used to refer collectively to ACLED’s violence against civilians, battles, and explosions/remote violence event types, as well as the mob violence sub-event type of the riot event type and the excessive force against protesters sub-event type of the protests event type. For more, see the ACLED Codebook.

Rebels: Armed, organized non-state actors that seek to challenge and topple or replace the government through the use of violence. These actors are also commonly referred to as insurgents or guerrilla fighters. They commonly coordinate with external forces and political militias/gangs. Examples include the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Allied Democratic Forces in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda, and Southern Transitional Council armed forces in Yemen.

Rioters: Individuals who engage in violence during demonstrations and mob violence events. Violence can be directed against people, property, or both. Examples include the 2020 Delhi riots in India and riots against COVID-19 restrictions.

Vigilantes/Mobs: A group of individuals engaging in extrajudicial violence meant to punish a crime, perceived crime, or social infraction.3Bateson, R. (2021). "The Politics of Vigilantism." Comparative Political Studies 54.6: 923-955. Examples include mobs engaging in the justicia comunitaria lynchings in Bolivia, especially within Indigenous communities, and lynching mobs in Bangladesh.

Violence Targeting Civilians: A category that encompasses all events of political violence that target civilians. This includes a broader scope than the violence against civilians event type (sexual violence, attack, and abduction/forced disappearance sub-event types). It is inclusive of the aforementioned sub-event types, the excessive force against protesters sub-event type, as well as explosions/remote violence and riots event types which involve civilians or protesters, but excludes the peaceful protest and protest with intervention sub-event types. Violence targeting civilians is typically used in ACLED analysis because it reflects the widest scope of violence faced by civilians recorded in the dataset.

Data Sources

ACLED data on political violence from the 12 months preceding the latest version of the Index are used to create the four indicators (e.g. July 2022 to July 2023 for the 2023 mid-year update). All ACLED events are collected using the same methodology, allowing a comparison of event numbers for political violence. Political violence events include the ‘Battles’, ‘Explosions/Remote violence’, and ‘Violence against civilians’ event types, as well as the ‘Mob violence’ and ‘Excessive force against protesters’ sub-event types.

Figures on exposed populations are derived using data from WorldPop.

To determine the overall ranking of countries in the Index, ACLED first ranks each country within each of the four indicators. An average ranking is calculated for each country based on those composite rankings, forming the final, overall ranking of the Index.

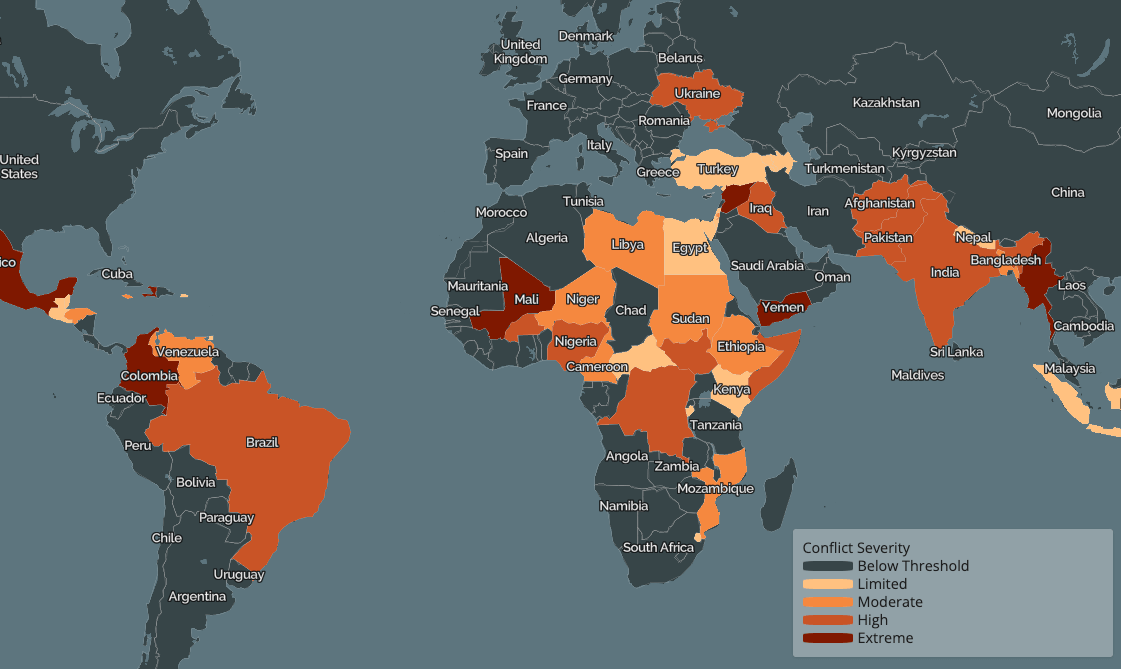

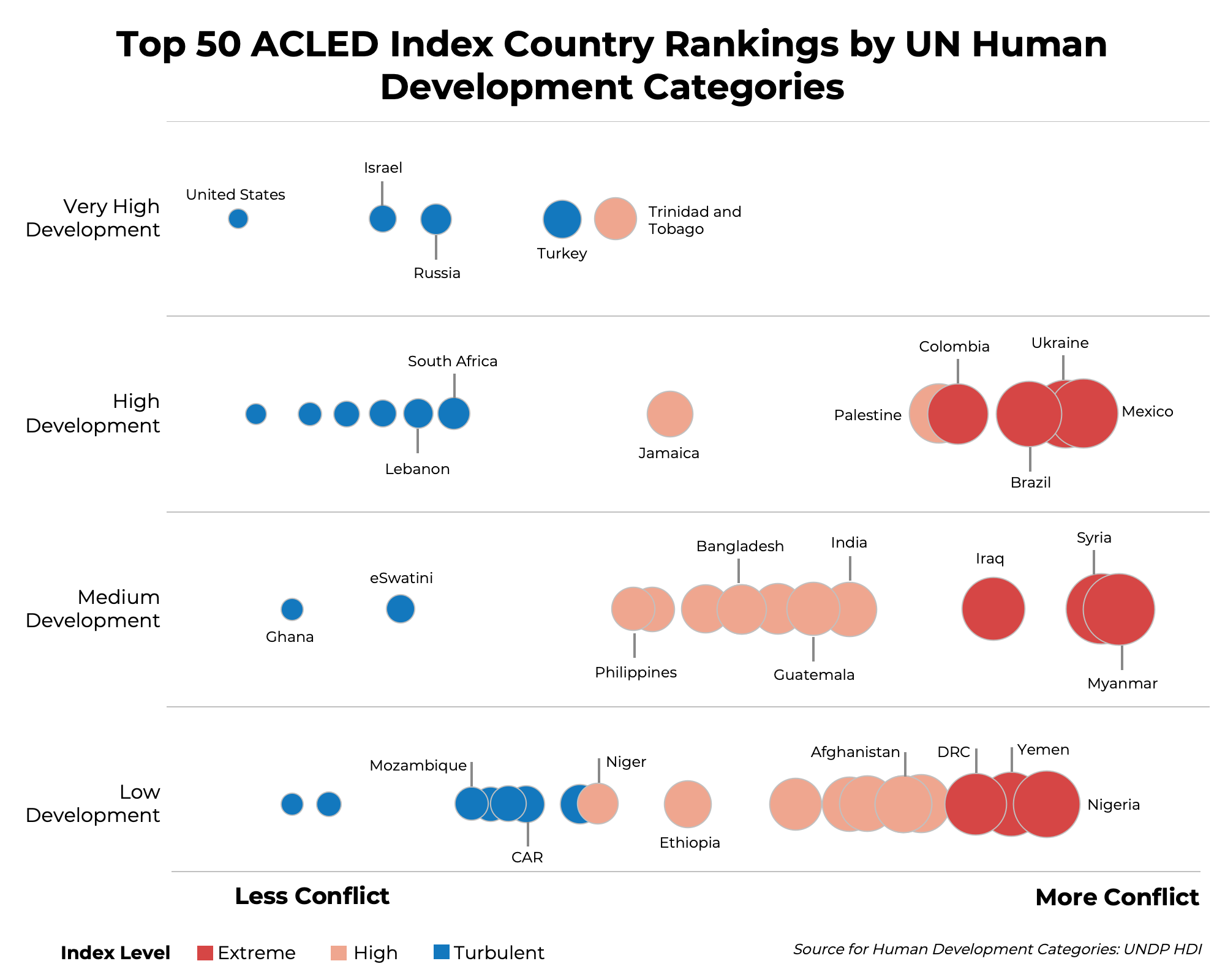

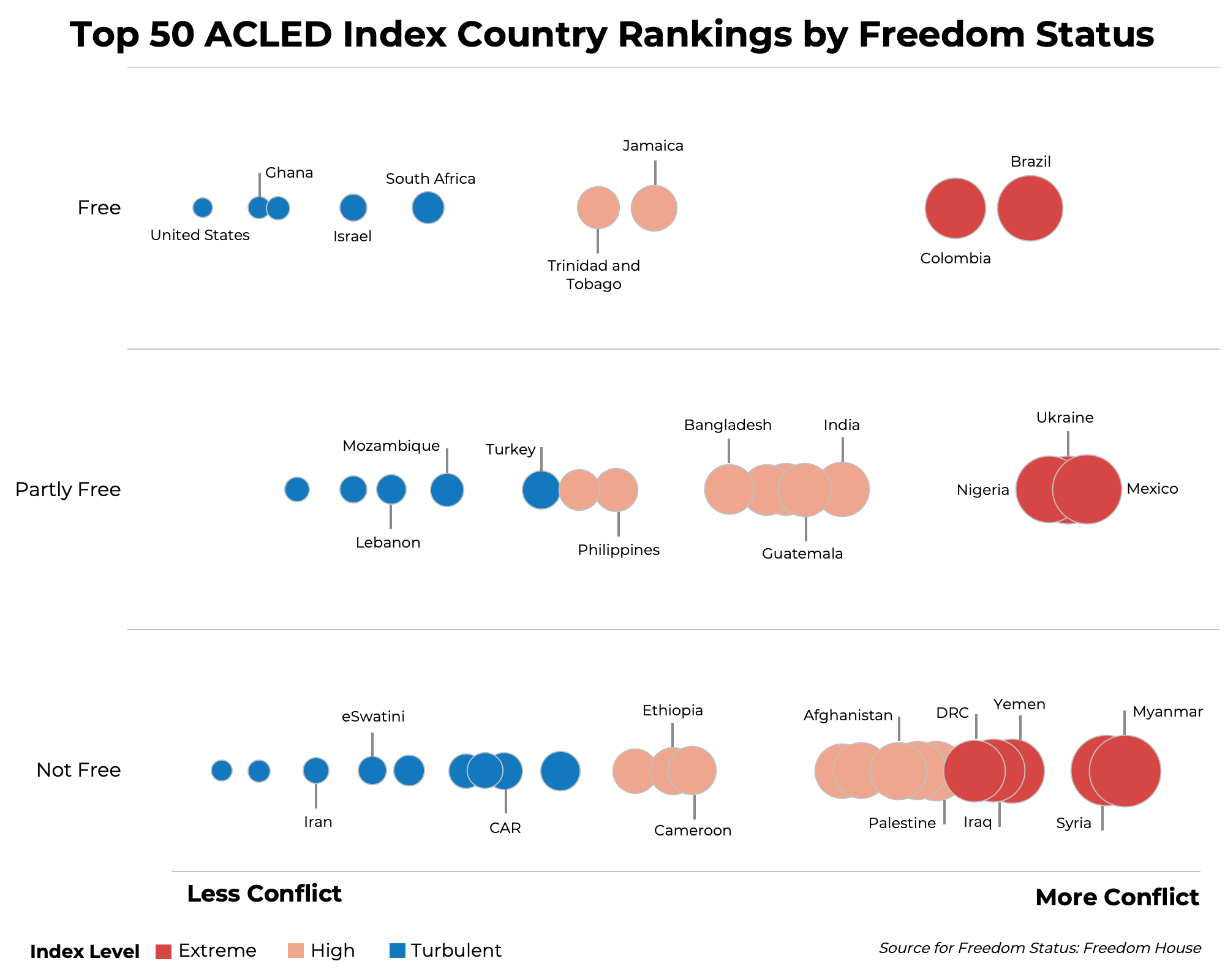

A country’s overall ranking on the Index determines their level of conflict. The top 10 countries in the Index are in the ‘Extreme’ category, followed by the next 20 countries in the ‘High’ category, and finally the next 20 countries are in the ‘Turbulent’ category. The remaining countries are in the ‘Low/Inactive’ category.

The 50 countries and territories in the ‘Extreme’ to ‘Turbulent’ categories account for 97% of all political violence events recorded by ACLED. The remaining 3% of political violence events are distributed across 117 other countries and territories.

As of the 2023 mid-year update, approximately 73% of all political violence took place in the countries with ‘Extreme’ conflict levels. Nineteen percent of political violence events occurred in countries with ‘High’ conflict levels, followed by 4% in countries or territories with ‘Turbulent’ conflict levels. The countries with ‘Low/Inactive’ conflicts made up 3% of political violence events recorded by ACLED.

The ACLED Conflict Index assesses every country and territory in the world according to four indicators – deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion, and armed group fragmentation – based on analysis of political violence event data collected for the past year. The top 50 ranked countries and territories are experiencing extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict.

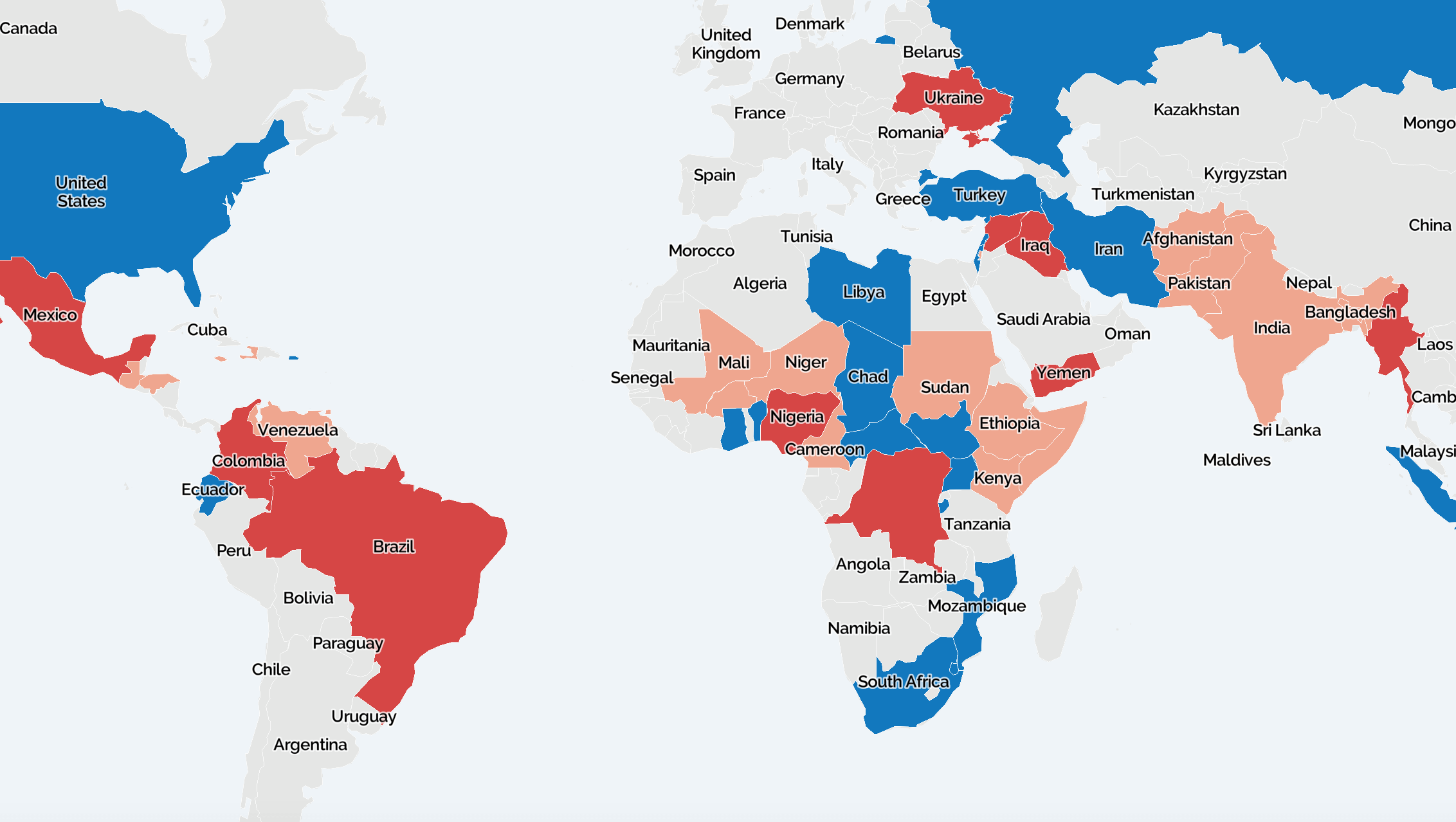

Explore the interactive map and overview below for more information about the Index’s findings and check the sidebar for a methodology explainer. Visit the Conflict Index Dashboard for access to further resources and data downloads.

Conflict Index Overview

ACLED’s Conflict Index answers three questions:

How much conflict is occurring in the world?

Conflict is widespread and pervasive. ACLED collects data for more than 240 countries and territories in near real time, and the majority – 167 – saw at least one incident of political violence in the past 12 months. Over 139,000 political violence events were recorded worldwide during this period, resulting in a conservative estimate of more than 147,000 fatalities.

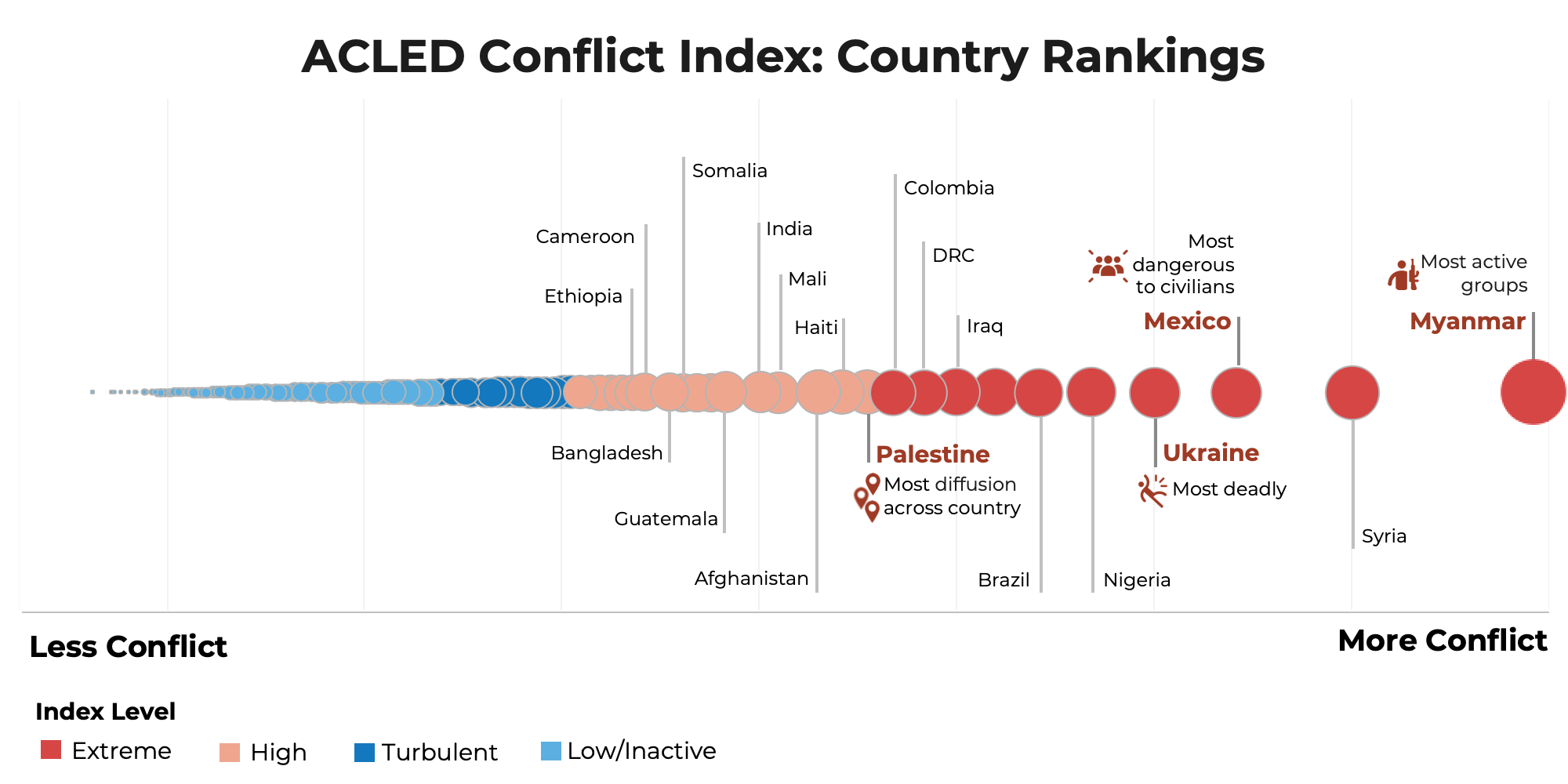

Analyzing the intensity, frequency, and form of violent events allows for further investigation into different levels of conflict. Drawing on the past year of data, the ACLED Conflict Index assesses levels of political violence according to four key indicators: deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion of conflict, and the number of active non-state groups (or fragmentation). Each country is ranked within each of these four indicators, which determines its overall ranking on the Index (see Methodology sidebar for more). A country’s place on the Index (see graphic below) represents its overall conflict level compared to other countries from July 2022 to June 2023.

Where is conflict happening?

Some level of conflict occurs in almost every country, but the highest levels are found in 50. These countries are ranked by the Index according to the four aggregated indicators, and categorized as ‘extreme,’ ‘high,’ or ‘turbulent.’ The top 50 ranked countries account for 97% of all political violence events recorded for the past 12 months.

| Index Rank | Country/Territory | Index Level |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myanmar | Extreme |

| 2 | Syria | Extreme |

| 3 | Mexico | Extreme |

| 4 | Ukraine | Extreme |

| 5 | Nigeria | Extreme |

| 6 | Brazil | Extreme |

| 7 | Yemen | Extreme |

| 8 | Iraq | Extreme |

| 9 | Democratic Republic of Congo | Extreme |

| 10 | Colombia | Extreme |

| 11 | Palestine | High |

| 12 | Haiti | High |

| 13 | Afghanistan | High |

| 13 | Burkina Faso | High |

| 15 | Mali | High |

| 16 | India | High |

| 16 | Sudan | High |

| 18 | Guatemala | High |

| 19 | Pakistan | High |

| 20 | Honduras | High |

| 21 | Somalia | High |

| 22 | Bangladesh | High |

| 22 | Kenya | High |

| 24 | Cameroon | High |

| 25 | Ethiopia | High |

| 26 | Jamaica | High |

| 27 | Venezuela | High |

| 28 | Philippines | High |

| 29 | Trinidad and Tobago | High |

| 30 | Niger | High |

| 31 | South Sudan | Turbulent |

| 32 | Turkey | Turbulent |

| 33 | Puerto Rico | Turbulent |

| 34 | Central African Republic | Turbulent |

| 35 | Burundi | Turbulent |

| 36 | Uganda | Turbulent |

| 37 | Mozambique | Turbulent |

| 38 | South Africa | Turbulent |

| 39 | Russia | Turbulent |

| 40 | Lebanon | Turbulent |

| 41 | eSwatini | Turbulent |

| 42 | Indonesia | Turbulent |

| 42 | Israel | Turbulent |

| 44 | Iran | Turbulent |

| 45 | Benin | Turbulent |

| 46 | Ecuador | Turbulent |

| 47 | Chad | Turbulent |

| 47 | Ghana | Turbulent |

| 49 | Libya | Turbulent |

| 50 | United States | Turbulent |

The Index shows that conflict is widespread, but not equally distributed or present in the same form across all countries.

There are multiple types of conflict, from civil wars and insurgencies to cartel competition and social violence. The countries that rank highly on the ACLED Index differ substantially in the types of conflict and violence they experience, even while many share levels of deadliness, danger, diffusion, and fragmentation. Violence in Yemen looks very different from violence in Brazil. Colombia’s conflicts are not the same as Syria’s, although both have entered into a ‘post-civil war’ phase.

In the past 12 months, the most violent country measured by event count is Ukraine, averaging over 950 political violence incidents per week, and accounting for 36% of all political violence events occurring in the past year. Ukraine is also the deadliest, with over 36,000 recorded fatalities in the past year.

Myanmar is home to the highest number of non-state armed groups, where local militias have frequently emerged to defend communities and engage in the ongoing conflict. More than 1,500 distinct actors have been recorded, at 47% of all non-state armed groups active globally in the past 12 months. Each group in Myanmar, on average, is involved in eight violent events per year, but groups drastically vary in the level of violence they engage in.

The most widespread conflict in terms of geographic diffusion is in Palestine, where high levels of violence affected over 60% of its territory throughout the past year. While smaller countries are more likely to rank highly on this indicator, violence also remains highly diffuse in places like Syria, which registered high levels of conflict across 10% of the country over the past year.

Mexico is the country that is most dangerous for civilians: ACLED records more than 5,000 incidents of violence directly targeting civilians across the country over the past 12 months. The threats to many civilian communities in Mexico are higher than those even in more violent conflict contexts.

Countries with ‘extreme’ and ‘high’ levels of conflict share some key characteristics. Many are home to conflicts that are not traditional insurgencies, but still have more violent events and fatalities than countries experiencing active civil wars. The forms of conflict that are currently most common around the world look more like the violence patterns in Mexico and Myanmar, and less like traditional insurgencies where one group wrestles with a government for control or territory. Mexico, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Brazil, and Iraq host violence levels that far exceed those associated with traditional wars. They also host multiple conflicts that differ in both targets and intended outcomes, and these conflicts do not often overlap. This means that governments frequently find themselves fighting multiple conflicts at once, and communities are exposed to varied types of violence.

Violence in countries experiencing ‘extreme’ and ‘high’ conflict levels typically also involves many active armed, organized groups. These groups fight each other as frequently as they clash with government security forces. Militias, rather than rebels, increasingly play a leading role in these conflicts.

Conflict is growing fastest in middle-income, democratizing countries. Middle-income countries are experiencing the greatest rise in conflict. Poverty is not a precursor to conflict, and wealth is not a guarantee of peace. In the graphic below, the top 50 countries in the ACLED Index are placed across the UN Human Development Index. As this comparison demonstrates, many countries with ‘extreme’ or ‘high’ levels of conflict are places with high and sustained levels of economic and social development.

Democracy does not protect countries from violent politics. In countries transitioning to democracy, or regressing from democracy, new forms of political competition can encourage conflict. Democratic shifts across the world have reduced the likelihood of traditional civil wars, and increased the likelihood of militia activity and political violence. Countries with “partly free” systems, according to Freedom House classifications, have elections, leader turnover and removal, inclusive representation, and other features of democracy, but often experience high levels of political violence, as shown in the graphic below.

Is conflict worsening or improving?

As of July, 19 countries have seen improvements to their ACLED Index rankings during the five-year period between mid-2018 and mid-2023, and 19 have seen worsening levels of conflict. Fourteen countries have remained in the ‘extreme’ or ‘high’ conflict level categories consistently, with no change between 2018 and 2023. Overall, of the 50 countries ranked at the top of the Index, over half (39) are experiencing sustained or escalating levels of conflict compared to 2018.

Change categories:

- ‘Worsening’ countries moved into a higher level of conflict between 2018 and 2023 (e.g. from ‘Turbulent’ to ‘High’)

- ‘Improving’ countries moved into a lower level of conflict between 2018 and 2023 (e.g. from ‘High’ to ‘Turbulent’)

- ‘Consistently Extreme/High’ countries remained in either the ‘Extreme’ or ‘High’ category between 2018 and 2023

- ‘Consistent’ countries remained in either the ‘Turbulent’ or ‘Low’ category between 2018 and 2023

Rank Change:

The rank change reflects the number of positions a country moved up or down in the rankings from 2018 to 2023. Positive numbers indicate the country climbed in the rankings (indicating a worse conflict situation), while negative numbers reflect a drop in the rankings (indicating an improved conflict situation).

Note: The United States is in the top 50 countries ranked by the Index, but ACLED’s historical data coverage for the country extends to 2020, not 2018. Therefore, the United States is not included in the comparison to 2018 displayed below.

| Country/Territory | Change Category* | Rank Change* |

|---|---|---|

| eSwatini |

Worsening

|

|

| Haiti |

Worsening

|

|

| Ecuador |

Worsening

|

|

| Burkina Faso |

Worsening

|

|

| Benin |

Worsening

|

|

| Puerto Rico |

Worsening

|

|

| Myanmar |

Worsening

|

|

| Ukraine |

Worsening

|

|

| Guatemala |

Worsening

|

|

| Niger |

Worsening

|

|

| Ghana |

Worsening

|

|

| Bangladesh |

Worsening

|

|

| Israel |

Worsening

|

|

| Chad |

Worsening

|

|

| Kenya |

Worsening

|

|

| Colombia |

Worsening

|

|

| Trinidad and Tobago |

Worsening

|

|

| Jamaica |

Worsening

|

|

| Democratic Republic of Congo |

Worsening

|

|

| Mali |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Palestine |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Sudan |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Honduras |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Pakistan |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Cameroon |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Ethiopia |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Nigeria |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Mexico |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

0 |

| Brazil |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

0 |

| Syria |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Iraq |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Yemen |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Venezuela |

Consistently Extreme/High

|

|

| Mozambique |

Consistent

|

|

| South Africa |

Consistent

|

|

| Iran |

Consistent

|

|

| Indonesia |

Consistent

|

|

| Uganda |

Consistent

|

|

| Russia |

Consistent

|

|

| Turkey |

Improving

|

|

| Afghanistan |

Improving

|

|

| India |

Improving

|

|

| Somalia |

Improving

|

|

| Lebanon |

Improving

|

|

| Central African Republic |

Improving

|

|

| South Sudan |

Improving

|

|

| Philippines |

Improving

|

|

| Burundi |

Improving

|

|

| Libya |

Improving

|

|

Downloads & Tools

Access a data file with ACLED Conflict Index results for all countries and territories, including Index level, overall Index ranking, and each individual Index indicator score. To access the underlying ACLED event data, use our data export tool or curated data files.

Interactive Conflict Index Dashboard

For more information about past and present Index results, use our interactive dashboard to access additional tools, resources, and data downloads. Use of the tool requires registration for a free account.

Additional Reports

Learn about the first version of the ACLED Conflict Index and its initial findings for 2022.