Widespread dissatisfaction over property rights continues to represent a significant amount of political activity in India. President Modi’s recent effort to reform India’s notoriously dysfunctional property laws has triggered hundreds of protests, galvanizing political parties across the spectrum. Although the bill has yet to pass India’s upper parliamentary house, political parties have used the momentum behind the movement to unite in opposition against the Modi-led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government. Their efforts have often fueled further agitation among farmers, leading to an increase in protests over the last two months throughout India. The vociferous protests are the strongest indicator that Modi’s political honey-moon has ended, thus jeopardizing his ability to implement pro-business reforms.

In March, the BJP passed an amendment to modify existing property laws, easing the rules for companies to acquire land for private development (Indian Express, March 2015). Known as the Land Bill, the amendment removes a previous requirement that projects carried out by private companies must have consent from at least 70 percent of residents in an area before their land could be bought for development. Additionally, the amendment removes the need for companies to assess the social impact of acquiring land for private development.

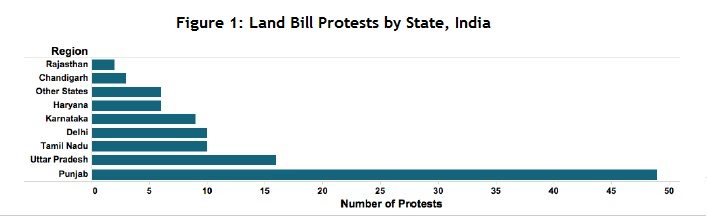

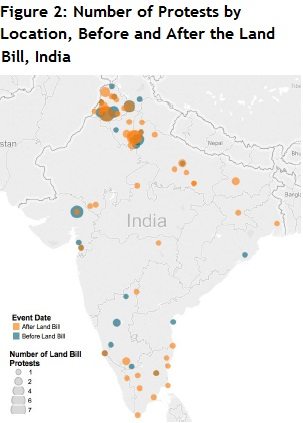

Legislative efforts to pass the bill sparked prolonged demonstrations across India beginning as early as January. Over the last two months, there have been 123 reported instances of riots and protests concerning land reform. Demonstrations are most frequent in Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, where farming constitutes a large fraction of the local economy. Protesters from rural communities have also undertaken lengthy marches to the nation’s capital to trumpet their message and draw attention to their con-cerns. Since February, 17% of land-reform protests have occurred in Delhi. In one notable event, 5,000 farmers from Haryana marched 60 miles to Delhi in February to express their opposition to the land bill amendment (Indian Express, May 2015). The event disquieted BJP members enough for them to consider modifying the original amendment (NDTV, February 2015).

Protests are frequently organized by opposition parties eager to absorb disaffected voters. The Indian National Congress, a long-standing BJP rival, and the Aam Aadmi Party, a recently created anti-corruption party, have been involved with over fifty percent of the demonstrations since February. In wake of the Land Bill, the INC and AAP’s efforts to label Modi’s BJP party as anti-farmer and anti-poor have struck a chord in a nation where nearly half the workforce depends on agriculture (CIA, 2012).

The INC and AAP have tapped into deep-seated unrest among farmers currently experiencing a dire farming cri-sis. Droughts, crop shortages, and price inflation of cash crops have imperiled their livelihoods (The Guardian, May 2015). As land-reform critics stoke fear among rural populations, farmers continue to appear at INC and AAP-led demonstrations.

The extent of the dissatisfaction is most evident in recent election results. Despite having widespread support the previous year, the BJP were resoundly defeated by the AAP in the Delhi local assembly election last month (Times of India, 2015). The AAP’s landslide victory (gaining 67 out of 70 seats) is significant, as the Delhi elections are consid-ered a bellwether of national sentiment. If the election is an indicator of larger trends, BJP’s losses throw into question the future of the BJP party and Modi’s efforts to push through pro-market policies.