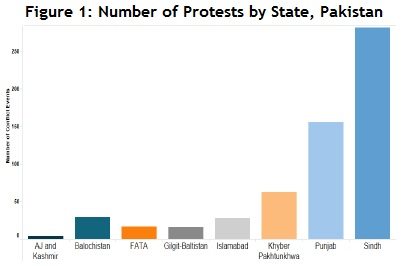

Since January 2015, there have been 269 protests in Sindh. In comparison, Punjab, which is the province with the second highest number of protests in Pakistan, has had 145.

Sindh province is characterized by a variable population density across regions, with Karachi being an urban, financial, and political hub. Rural villages surrounding Karachi are the agricultural backbone of the nation’s economy, as well as the force behind a strong, separatist, Sindhi identity that has its roots in leftist thought. This variation in demographic and social landscapes provides the appropriate contexts within which the different types of protests that take place throughout the province including unionised protests, political party protests, nationalist/separatist protests, religious protests, and civil society protests.

The All Pakistan WAPDA Hydro Electric Workers Union, the main union for the nationalised electricity provider (WAPDA), has been protesting against the proposed privatisation of the authority, at least twice weekly since January. These protests are coordinated province-wide -and at times nationwide- with workers across localities in rural Sindh going on strike and holding public demonstrations. Several hundred protestors attend the events. School and University teacher associations also feature prominently in protests in Sindh, however almost all other unionised protests are held to demand the release of salaries, particularly in government jobs, where salaries have gone unpaid at times for over 8 months.

Political parties use street pressure in Karachi to express discontent with, or support for, current affairs that have gained traction in the local media. The emphasis during such protests is on validating statements made by politicians in the media by showing democratic support. The rivalries between the MQM, PPP and PTI in Karachi often time spills over during protests, which result in riots taking place.

Nationalist/ Separatist protests are unique to Sindh province. Every week since January 1st 2015 there has been at least one demonstration attended by several thousand individuals that focuses on either the influx of non-Sindhi’s in the province, or the importance of maintaining a strong, detached province from the centre. Such nationalist groups have had violent pasts, linked with attacks on governance structures like railway tracks in the early 2000s and before, earning some of them proscribed statuses. However, today they are not seen as direct threats to the state after adopting a democratic approach. They often boycott elections on principle, holding that the state discriminates against them; however they have large followings that result in mass rallies and province-wide strikes.

Protests by banned religious outfits occur regularly in Sindh, and while the environment has been challenged by civil society groups, the government has often times sided with groups it has itself proscribed. The Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat is one such example. The group has been banned since 2001 but until the beginning of this year was regularly protesting against the discrimination of its members as well as promoting hate speech. When two groups of protestors were convening at the same spot, a civil society group chanting against the hate speech indorsed by the ASWJ, and the ASWJ, the police forced civil society members to disperse and clear the area for the ASWJ members. This highlights the precarious relationship between religious organizations and the state in Pakistan, particularly in Sindh and in Karachi, which is arguably the only metropolis where the Taliban have a stronghold.

Protests movements in Sindh stand out in Pakistan not just because of the numbers, but also because of the type of protests. Groups that are not active in the government, such as unions and separatist rights group, have regular street presence provincewide, more so than active political parties. Civil society groups protest regularly as well, with no political affiliations and can also question the power structures in place and gain public and media attention. For Pakistan, the case of protest movements in Sindh highlights the further democratization of a country that in its 68 years has only seen one democratic transition of power.