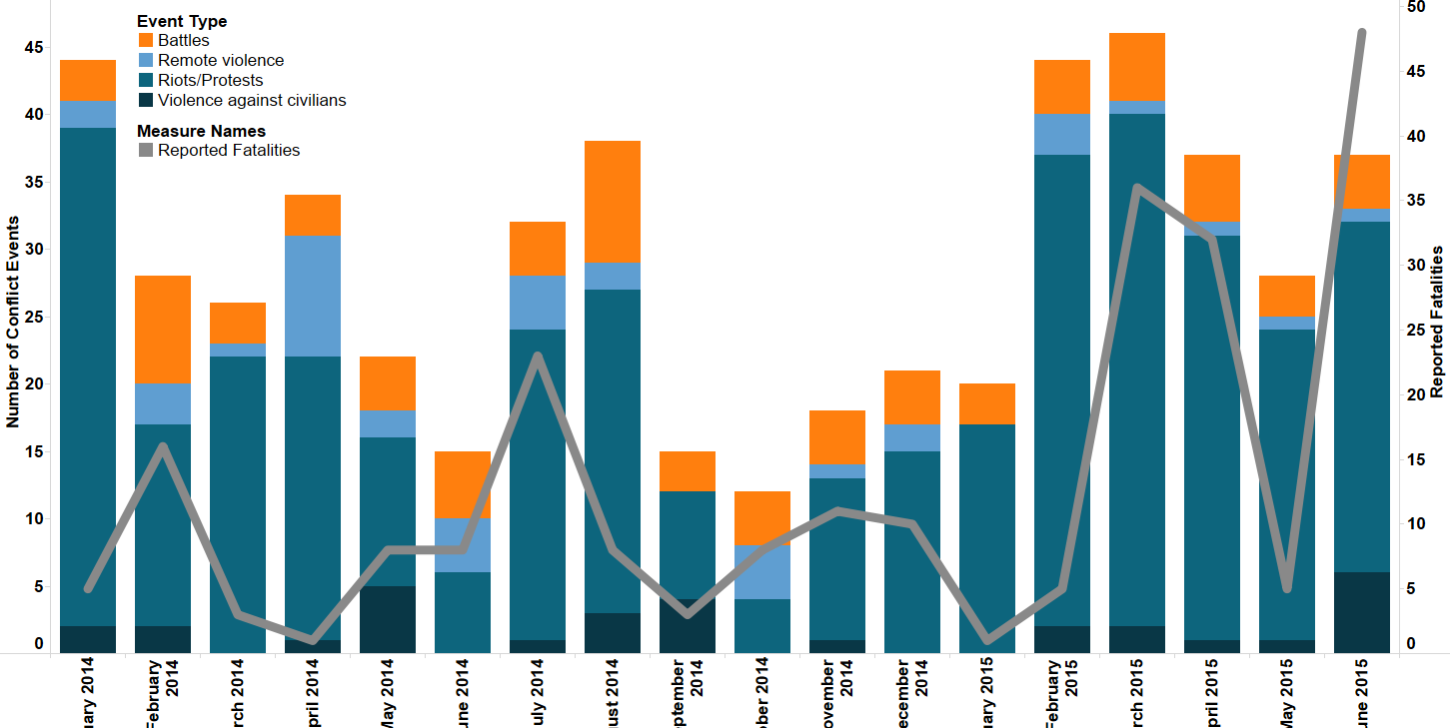

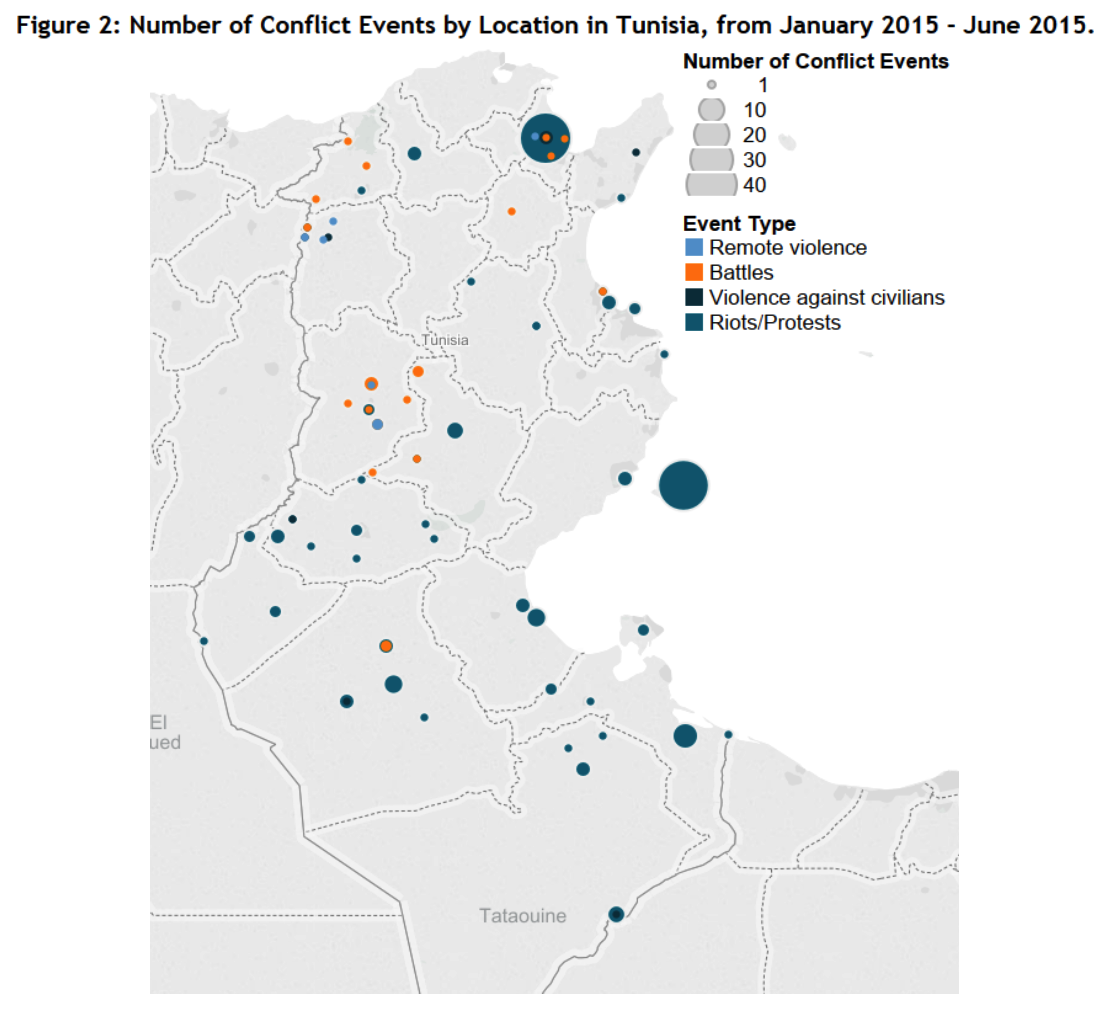

While a new series of violent events targeted civilians and security forces in June, Tunisia witnessed a sustained increase in political violence (see Figure 1). Not only is the number of conflict events rising, reported fatalities were also at their highest since January 2011. Four national guards died in two separate shoot-outs with Islamist militias in the western regions of Kasserine and Jendouba. These violent clashes between security forces and armed groups occurred after the launch of large-scale military operations in the heights of Kasserine, which resulted in the killing of at least four Islamist militants at the beginning of June (Agence France Presse, 15 June 2015). Furthermore, another attack targeted Tunisia’s tourism industry, three months after the assault on Bardo National Museum in Tunis: a young Kairouan-born Islamist, allegedly trained in a militant camp in Libya, stormed a tourist resort near the coastal locality of Sousse killing 38 foreign nationals (BBC, 30 June 2015). The raid, claimed by the Islamic State (IS), represented the deadliest attack in Tunisia’s modern history and a challenge to the country’s democratic institutions.

These patterns reveal an evolution in Tunisia’s conflict dynamics. Although the escalation of political violence has its roots in the post-revolutionary conflict cycle (ACLED, June 2015), competition within the Islamist camp seems to be instrumental in accelerating this process. Despite the seemingly coherent common ideological framework, the main Islamist militias have been pursuing different, and sometimes competing, strategies in Tunisia. The Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade, a prominent armed militia linked with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), claimed responsibility for a number of attacks against security forces and politicians. Although its position vis à vis IS is unclear, this militant group has established a ‘pocket of resistance’ in the remote area of Jebel Chaambi, near Kasserine, since 2013 (Reuters, 19 March 2015; Pusztai, 30 June 2015).

By contrast, the IS, which has no operative base in the country, is seeking to gain a foothold by sponsoring attacks against sensitive targets, namely foreign tourists. As noted by an external observer, IS’s strategy is aimed at provoking “government clampdowns that fuels a popular sense of injustice, boosting its recruitment by winning hearts and minds” (The Independent, 2 July 2015). In an attempt to gain higher visibility and attract a greater number of potential militants, this process of strategic tactical differentiation may induce both groups to scale up their insurgencies. Moreover, although these patterns reveal local dynamics of contention, they seem to reflect a wider shift in the global Islamist movement (Libération, 3 July 2015).

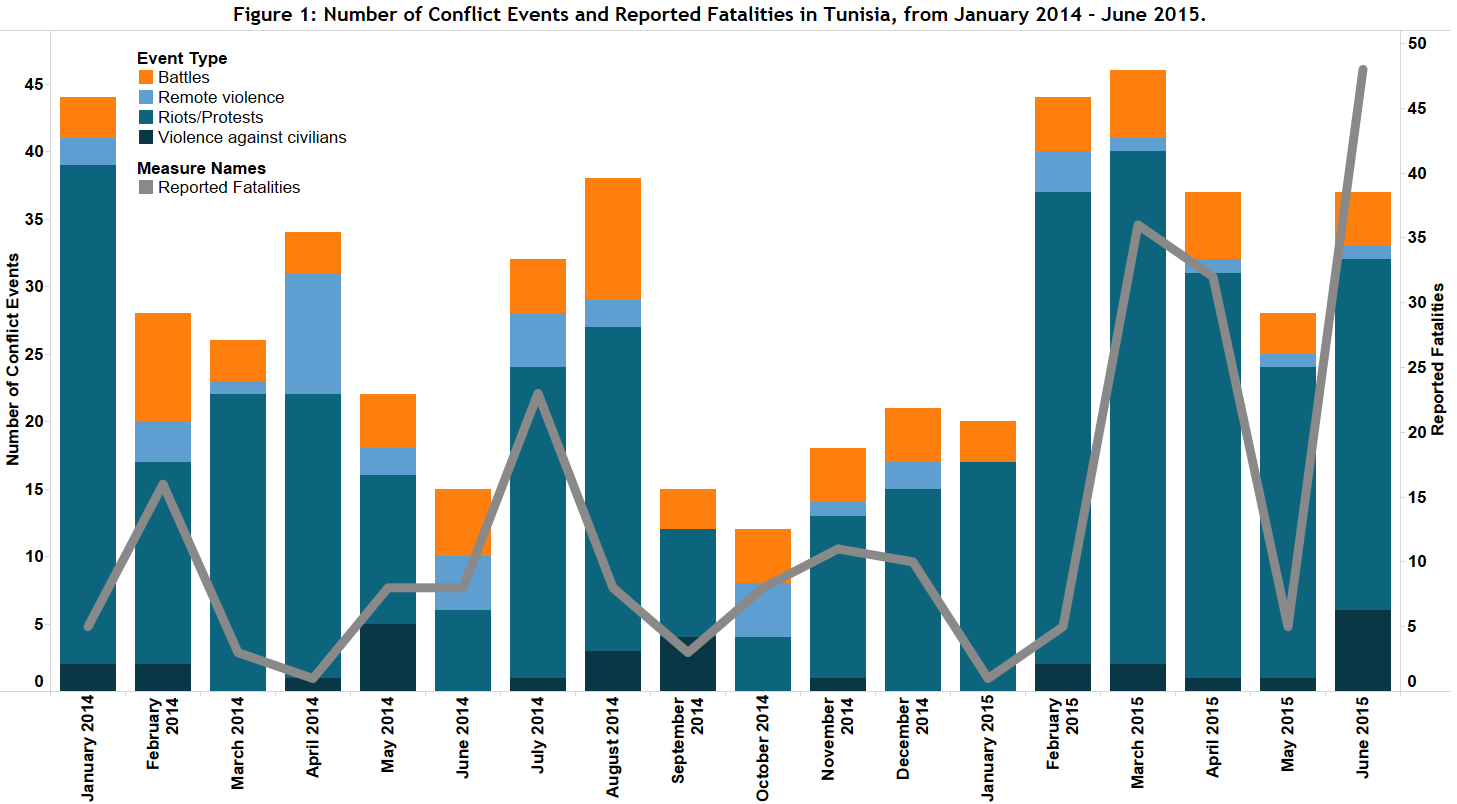

In addition to militia activity and organised violence, protesting and rioting have also been a major source of conflict in 2015. Whilst the increase in protesting activity points to the dissatisfaction for the persistence of a problematic socio-economic situation (high unemployment, regional inequalities, rampaging corruption), unrest has intensified greatly in the past few months. Figure 2 reveals a greater incidence of riots and protests in central and southern regions, where economic indicators have stagnated in the aftermath of the revolution. The provinces of Tozeur and Kebili recently witnessed violent incidents between demonstrators and police forces, whose severe repression contributed to ignite protests in distressed local communities. In order to counter the escalation of violence and restore security domestically, Tunisian authorities adopted draconian measures. Following the Sousse attack, the government decided to deploy 1000 additional security forces throughout the country, while at least 80 mosques accused of fuelling violence were shut down.

Furthermore, President Béji Caïd Essebsi declared a temporary state of emergency, which allows the government and the military to exercise exceptional powers for a period of thirty days (Jeune Afrique, 5 July 2015). However, it is not clear whether the security crackdown will be effective in reducing violent extremism. On the one hand, inadequate training and limited financial resources have hampered the reorganisation of security forces since the establishment of democracy. Several security failures have reportedly played a role in various attacks against military units and civilians (Jeune Afrique, 2 September 2014; The Telegraph, 30 June 2015). Therefore, providing financial and technical support to security forces would prove to be instrumental in restoring order. On the other hand, the government may be tempted to use its special powers (including imposition of curfew or prosecution of hostile demonstrators) to limit protest activity and suppressing dissent. Far from consolidating the fragile Tunisian democracy, non-targeted repression would accelerate an authoritarian turn while simultaneously feeding the ranks of insurgent groups.

In a country marred by an escalating cycle of violence and daunting economic prospects, difficult decisions await Tunisia’s political elites. Security clampdowns are unlikely to arrest the proliferation of violence effectively, as the recent example of Egypt seems to suggest. Rather than focusing merely on repression, Tunisian authorities should aim at improving the relations between the people and the government, by enhancing the accountability and the inclusivity of state institutions (The Guardian, 1 July 2015; Human Rights Watch, 7 July 2015). Without addressing the root causes of marginalisation and widespread malaise, radical groups have already are likely to prosper and to extend their outreach further, thus jeopardising Tunisia’s efforts towards democracy.

This piece was originally featured in the July 2015 ACLED Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringIslamic StateIslamist ViolenceLocal-Level ViolencePolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians