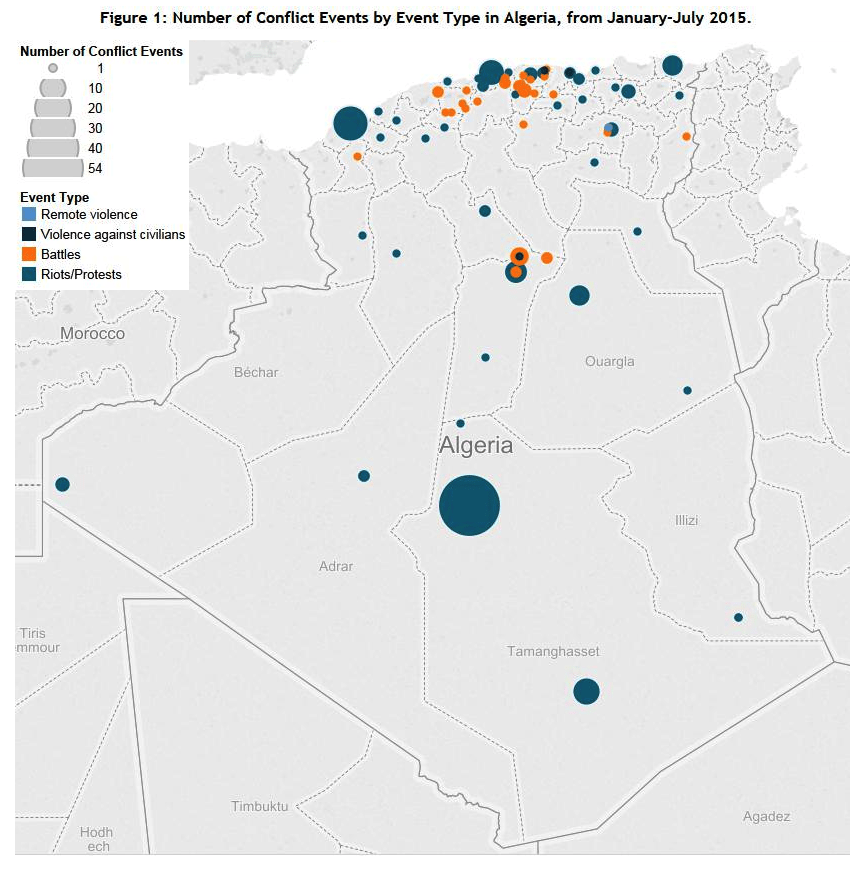

Despite its relative stability in a precarious regional context, a recurrence of violence in July has raised concerns over Algeria’s unresolved problems. A critical socio-economic situation is putting Algeria’s peripheral regions – where conflict activity has remained high since the beginning of 2015 (see Figure 1) – under constant pressure, exacerbating popular grievances and igniting long-lasting tensions.

Earlier this year, a protest movement emerged in the wilayas of Adrar and Tamanrasset over a proposed project of shale gas exploitation in the Ahnet Basin (ACLED, February 2015). On July 7-8, 23 people were reported dead during intercommunal clashes in the M’zab Valley, 600 km south of Algiers. After months of sporadic confrontations between the Mozabite Berber and Chaamba Arab communities, the towns of Guerrara, Berriane and Ghardaia saw an unprecedented escalation of violence that forced the police to intervene and restore public order (Al Jazeera, 10 July 2015). Although hostilities in Ghardaia region had been mounting since late 2013, when a Berber shrine was vandalised, the government has failed in containing violence between the two communities.

These episodes reflect Algeria’s problematic governance. While the 78-year-old President Abdelaziz Bouteflika vowed to bring about change by replacing senior security leaders after tensions in Ghardaia, plummeting global energy prices and shrinking foreign reserves are negatively affecting Algerian economy (Africa Confidential, 23 July 2015). Should these trends continue, the country’s ageing leadership may run out of means to buy off the loyalty of its citizens and secure stability as it did to avert revolt in 2011.

At the same time, military forces are grappling with frequent lethal incursions by Islamist groups. On July 16, nine soldiers were killed in an ambush carried out by Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQMI) in the northern region of Ain Defla (Radio France Internationale, 18 July 2015). This attack indicates that Islamists are attempting to extend their area of activity to outside the Kabylie, which includes the provinces of Tizi Ouzou, Boumerdes, Bouira and Bejaia, where armed groups have mostly operated in the past few years. It also points to the increasing pressure faced by AQMI, which has to expand its outreach in order to compete with other Islamist groups, including the Daesh-aligned Jund al-Khilafa.

According to local sources, AQMI’s leader Abdelmalek Droukdel would have reached a compromise with Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Al Mourabitoun group to counter the rise of the Soldiers of the Caliphate in Algeria (Africa Confidential, 23 July 2015). Belmokhtar, who was reported dead during a US air strike in Libya in June, had previously denied claims that his group pledged allegiance to Daesh. Although the Algerian security forces have thus far succeeded in restricting the operational capacities of Islamist groups, persisting instability in neighbouring Libya and Mali may increasingly spill across the Algerian borders.

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians