In the immediate aftermath of the Islamist attack on Marhaba hotel in Sousse, Tunisia’s government adopted urgency measures aimed at safeguarding tourist sites and preventing other attacks on Tunisian soil. Under the state of emergency declared by President Essebsi on July 4, thousands of army troops have been deployed nationwide for reasons of internal security, while unauthorised rallies and mosques were either banned or shut down.

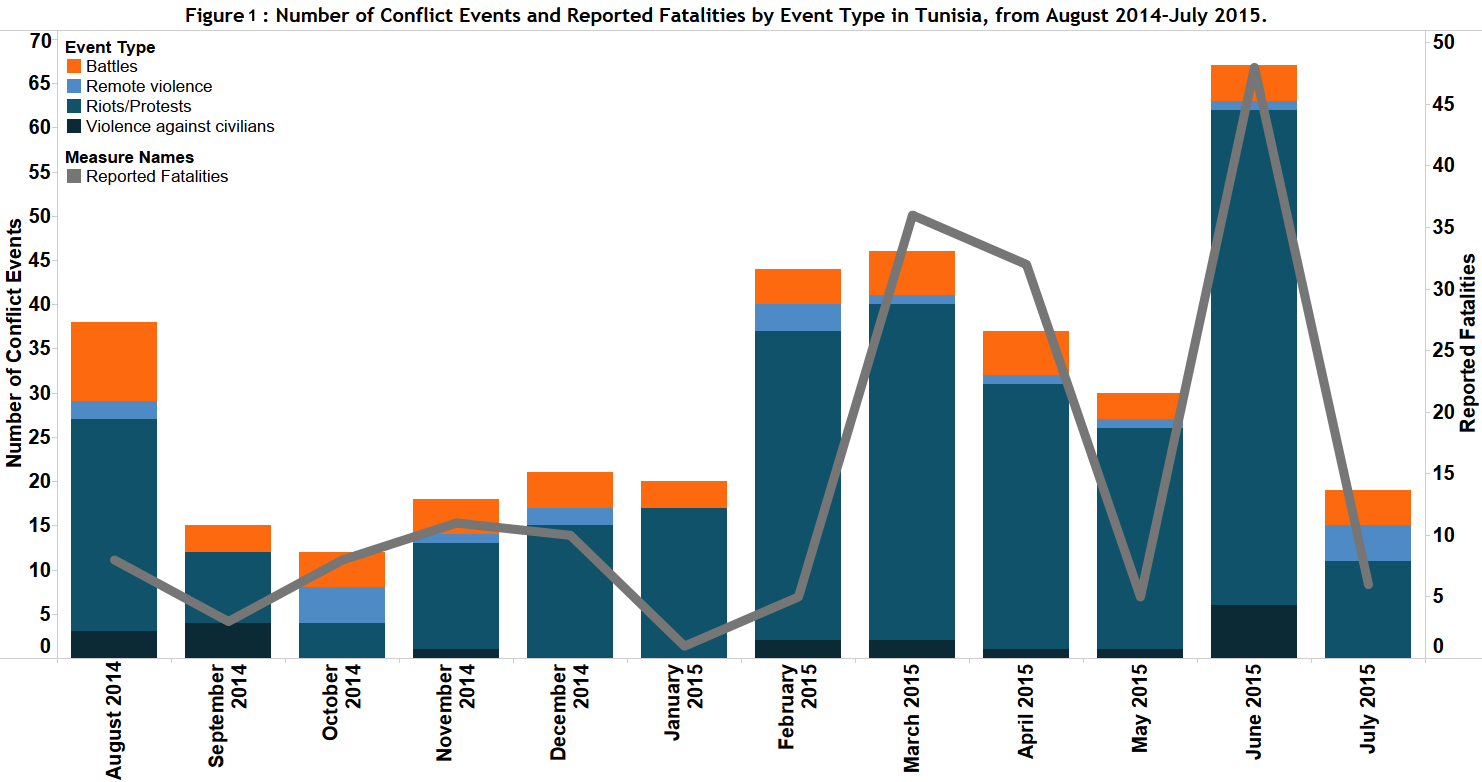

July’s conflict levels in Tunisia thus reflect these recent developments. The number of conflict events in July fell by more than 70% compared to the same period in June, when conflict levels reached their highest since January 2012. This general decrease notwithstanding, there exist significant differences in terms of conflict activity (see Figure 1). While riots and protests saw the most drastic decrease, due to the entry into force of governmental restrictions and the end of prolonged sit-ins in the periphery, Tunisian security forces conducted a series of military operations against Islamist militias. During two raids in Gafsa and Bizerte regions, the army killed six Islamist combatants, including a senior leader of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Okba Ibn Nafaa Brigade (France 24, 12 July 2015).

As the country begins to face the political and economic consequences of the recent attacks on security forces and foreign nationals, Tunisian authorities have launched a new security clampdown. On July 25, Tunisia’s Parliament passed an anti-terrorism legislation that extends the pre-trial detention from six to fifteen days and introduces capital punishment for terrorism-related charges, including the dissemination of information connected to terrorist attacks (Jeune Afrique, 25 July 2015). The adoption of the new anti-terrorism law, which replaces the previous one adopted in 2003 under Ben Ali’s regime, came a few days before the extension of the country’s state of emergency for an additional period of two months (Radio France Internationale, 31 July 2015).

Despite a nearly unanimous vote in Parliament, the measures introduced by the government attracted widespread criticism from human rights groups. Eight non-governmental organisations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, condemned Tunisia’s new antiterrorism law because it “imperils human rights and lacks the necessary safeguards against abuse” (Human Rights Watch, 31 July 2015). According to these NGOs, the law grants broad and ill-defined powers to security forces, while the extension of pre-trial custody exposes detainees to torture and mistreatment.

Prioritising security over human rights, the Tunisian government maintains that such repressive measures are necessary to restore the country’s internal security and confront radical groups effectively. However, repression alone will hardly contain violence in the medium and in the long term. Tunisian authorities will also need to focus on a comprehensive security sector reform that could root out corruption and prevent abuses of the armed forces (International Crisis Group, 23 July 2015). Should the government fail in improving the organisation and the conduct of its police, violent radical groups may succeed in attracting more militants while Tunisia’s fragile democracy will risk precipitating into further instability.

This report was originally featured in the August ACLED Conflict Trends Report.