On the 16 September, the Presidential Security Regiment (RSP), an elite unit within the Burkinabé army, staged a coup dissolving the transitional government that had been in power since November 2014, when a wave of popular unrest ended Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year rule. In a televised speech, the RSP announced the creation of a military junta known as National Council of Democracy (CND) led by General Gilbert Diendéré, RSP’s leader and staunch ally of Compaoré, while transitional President Michel Kafando and Prime Minister Isaac Zida were being held hostage in Ouagadougou (African Arguments, 18 September 2015).

After one week of protests throughout the country and negotiations within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), General Diendéré stepped aside, offering his apologies for the coup attempt (Agence France Presse, 23 September 2015). In turn, the reinstated President Kafando vowed to dissolve the RSP and to guide the country towards the elections scheduled on the 11 October. As the regular army assaulted RSP’s barracks in the capital city and the coup leader sought protection in the Vatican Embassy, General Diendéré was arrested on 1 October along with other prominent political figures that had been sympathetic to the short-lived junta, including former presidential candidate Djibril Bassolé (Jeune Afrique, 26 September 2015; 30 September 2015).

Behind this coup attempt lie a number of strategic calculations. Tensions between the transitional government and the RSP had been mounting over the past few months, when the unit led by Diendéré accused the executive of violating previous agreements regarding the RSP’s special status. Additionally, the newly-introduced Electoral Code banned several members of Compaoré’s ruling party, the Congress for Democracy and Progress (CDP), from running in the forthcoming elections, fuelling fears that the RSP could soon be disbanded (Africa Confidential, 25 September 2015). Facing the prospects of being reintegrated within the army and stripped of the long-standing privileges obtained during Compaoré’s era, the RSP resorted to a desperate move that in the end turned out to be unsuccessful.

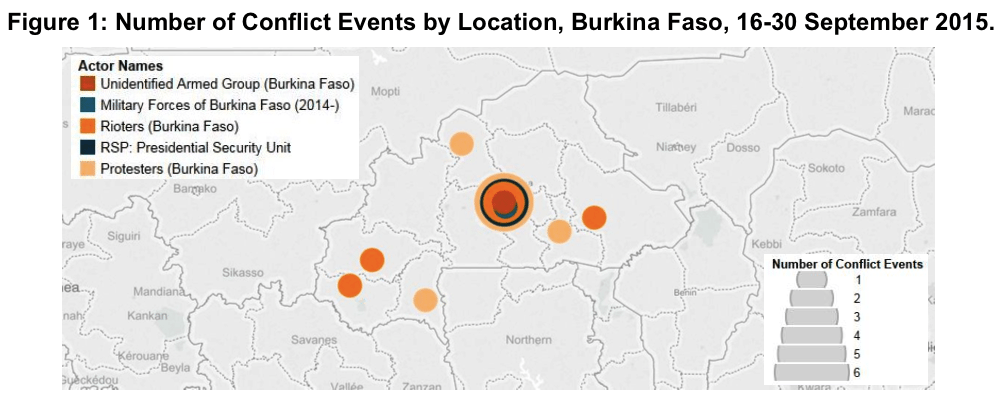

As in the case of the uprisings that ousted Blaise Compaoré in 2014, popular mobilisation was instrumental in putting down the coup. Protesters defied the imposition of the curfew by the RSP and responded to calls from trade unions and civil society organisations by taking to the streets, marching in protest and erecting barricades in Ouagadougou and elsewhere in the country. The RSP’s initial willingness to quell protests in the capital city, where confrontations between RSP and demonstrators resulted in several civilian deaths, eventually influenced the forms of collective action nationwide (Bertrand, 21 September 2015). Instead of gathering in large numbers as during the 2014 uprisings, protesters opted for more diffuse and small-scale mobilisation, which in several towns did not face any repression given the RSP’s limited outreach outside Ouagadougou (see Figure 1).

However, the foiled coup attempt reflected the enduring legacy of Blaise Compaoré and his allies on Burkina Faso’s political and economic life, revealing the several challenges that await the country’s political class.

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskPolitical StabilityRioting And ProtestsUnidentified Armed GroupsViolence Against Civilians