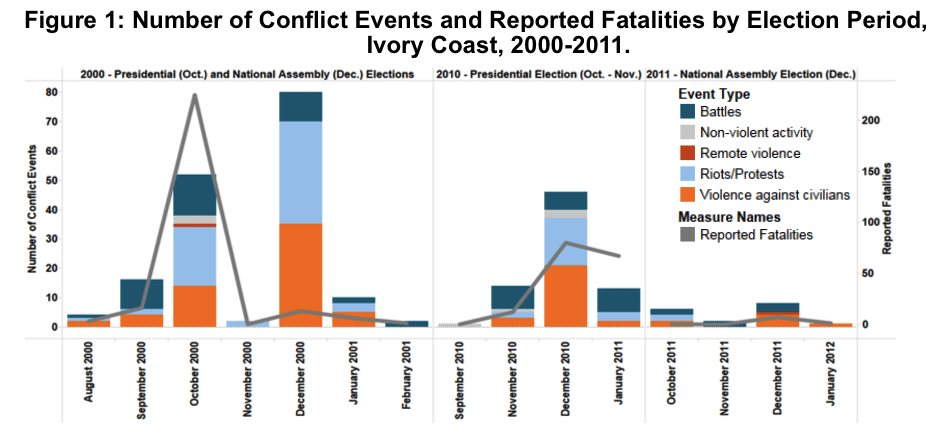

In mid-October 2015, Central African Republic (CAR), Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso will each hold elections. As Figure 1 shows, levels of violence during electoral periods are high in Ivory Coast: for example, the general elections in November 2010 resulted in a six-month civil war between militias of former President Laurent Gbagbo and the contested winner Alassane Ouattara. By contrast, CAR and Burkina Faso do not typically experience high violence around elections.

However, violent unrest led to the ousting of Burkinabé President Blaise Compaoré following his attempt to amend the constitution in order to run for a third term (Africa Confidential, 1 November 2014). In CAR, inter-communal violence and clashes between Seleka and Anti-Balaka militias have led to an ongoing civil war, potentially jeopardizing the electoral process. Electoral campaigns in all three countries, therefore, have been beset by tensions. In Burkina Faso, the transitional government, Conseil National de Transition (CNT) has established a new electoral code, which forbids anyone who supported Compaoré’s mandate extension from running for office (Africa Confidential, 1 May 2015). Furthermore, the presidential guard, Regime de Securité Présidentiel (RSP), which has remained a key player, has been under pressure to reform by the CNT. Possible reforms may include the RSP’s reintegration into the regular army, and other moves likely to foster dissatisfaction among its ranks (International Crisis Group, 24 June 2015).

Following the 2011 conflict in Ivory Coast, Gbagbo’s trial for crimes against humanity has weakened the opposition. Fears of violence from pro-Gbagbo supporters remain high, especially in the west of the country. Moreover, internal dissension within the ruling party, due to attempts by former rebel leader Guillaume Kigbafori Soro to take control, raise concerns for stability (Africa Confidential, 12 June 2015).

In CAR, the October election has been criticised for being held to hastily. The electoral registration system appears to exclude refugees and populations where Seleka remains active, with registration concentrated in the capital city (Africa Confidential, 10 September 2015). Furthermore, ongoing insecurity and underlying intercommunal tensions is likely to affect the environment within which the elections take place (International Crisis Group, 21 September 2015). Recent developments suggest that concerns about the peaceful conduct of elections are valid. Throughout September in Ivory Coast, riots and pro- tests in Abidjan concerned the legitimacy of Ouattara as a candidate (Voice of America, 11 September 2015). In CAR, violence at the end of August in Bambari — a region with recurring conflict between Seleka and Anti-Balaka and a site of intercommunal violence — demonstrates the sustained capacity of armed groups to disrupt elections (African Arguments, 2 September 2015). Finally, in Burkina Faso, the RSF’s coup attempt in early September has confirmed fears about the force’s disruptive role. Although the situation seems to have stabilized with the return of the transitional President and the resignation of RSF’s head, associated factions may still disrupt the electoral process.

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.

AfricaAnalysisElectionsPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians