While Algeria’s active role in the Malian and Libyan crises confirms its regional and international engagement, conflict dynamics point to the increasing vulnerability of its domestic economic and security prospects (International Crisis Group, 12 October 2015).

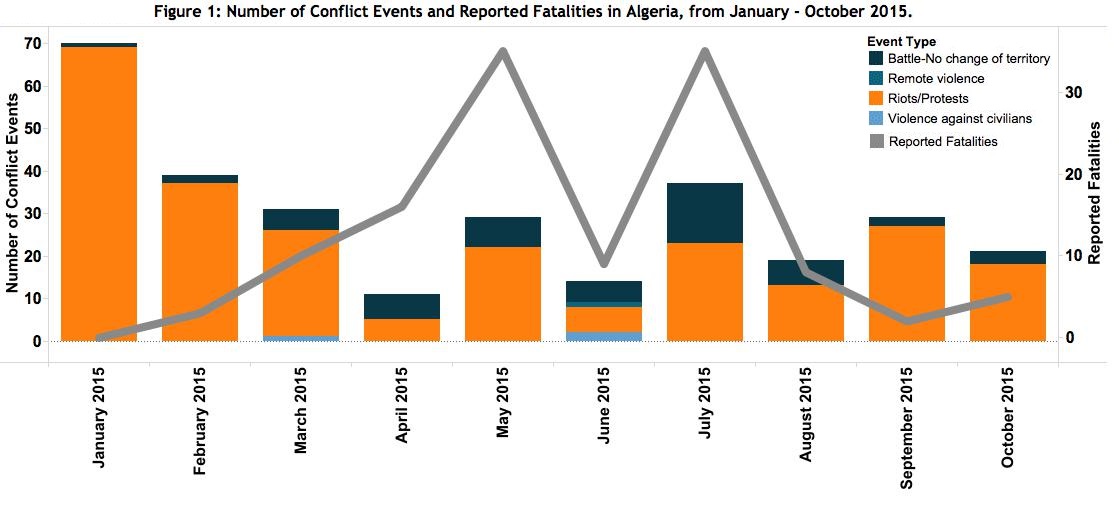

Over the last two months, northern Algeria experienced a series of service-delivery protests that saw local communities denouncing a lack of public services and marginalisation of rural areas. Although conflict levels have not risen significantly in absolute terms compared to previous periods (see Figure 1), the diffusion of protests reflects widespread popular discontent with the socioeconomic situation and the country’s ruling elites, the pouvouir. However, protest events remained spontaneous and short-lived despite persisting contestation, proving that the absence of strong socio-political networks, such as trade unions and parties, constitutes an important obstacle to wider mobilisation.

Worsening macroeconomic trends present an additional challenge to the Algerian government. In September, Algeria’s trade deficit rose up to 10.33 billion dollars, compared to 4 billion in the same period last year, 6 billion in May and 8 billion in July (Jeune Afrique, 21 October 2015). The economy is affected by falling hydrocarbons exports, which constitute the 95 % of all Algerian exports and have decreased by 41.41 % since January. The wave of unrest that followed the economic crisis of mid-1980s suggests that political stability will ultimately hinge on the government’s ability to address the economic crisis and promote social development.

Concerns for the future sustainability of Algeria’s governance also extend to the security sector. According to a report published by Transparency International, unchecked military spending and widespread defence corruption are undermining public trust in the government and in its armed forces, while feeding arms proliferation, organised crime and regional instability (Transparency International, 2015). The organisation ranks Algeria among the most corrupt countries in the region, revealing weak institutional oversight, lack of transparency and widespread nepotism and distrust. Whilst the link between corruption and conflict might be less direct than the report states, popular discontent with the corruption of the elites is more likely to increase in times of crisis.

In this context, Algeria’s military elites are undergoing a phase of major reorganisation (Jeune Afrique, 14 September 2015). Since 2013, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika has sacked a number of high-level officers in the Department of Intelligence and Security (DRS, Département du renseignement et de la sécurité), including Lieutenant General Mohammed “Toufik” Mediène, who led the DRS since 1990 and was forced into retirement in September. According to many observers, these changes at the top of Algeria’s security services do not reflect any substantial change in the current system of governance, nor the beginning of a democratic transition (Africa Confidential, 24 September 2015). They instead point to power struggles within the ruling elites over who will succeed Bouteflika, which may intensify in the near future.

This report was originally featured in the November ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.