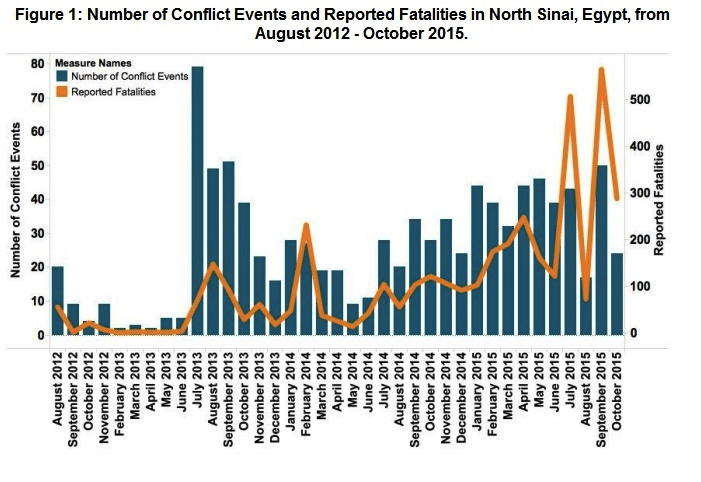

Despite a dramatic decrease in insurgent activity in North Sinai through October (see Figure 1), the Islamic State affiliate group ‘State of Sinai’ have claimed responsibility for downing a Russian passenger plane on 31st October. Although several rival statements have thrown the validity of the Islamic State’s claim into question – two days after the crash, the Russian airline Kogalymavia denied the possibility of technical failure or human error (Egypt Independent, 2 November 2015) and speculation of IS involvement continues to grow (The Telegraph, 3 November 2015) . If the State of Sinai’s claim is substantiated, this represents a significant escalation of violence and transformation in strategy since 1 July, after attempts to seize territory in Sheikh Zuweyid left 21 soldiers dead.

This change in tactic may represent a more wholesale re-branding of the Wilyat Sinai and a departure from the logic underlying its use of violence in the previous year. The majority of attacks in the towns of Al-Arish, Rafah and Sheikh Zuweyid often posed a direct rebuke of the Egyptian government’s aggressive response to demonstrators and sustained targeting of Muslim Brotherhood affiliates across Cairo and other large cities. Small-scale, tit-for-tat, and diffuse incursions targeted security checkpoints and the vehicles of police conscripts and army generals who were mostly off-duty. These sorties generally focused on inflicting damage in a ‘hit-and-run’, assassination-style fashion to express contempt for President Sisi’s draconian measures. For this reason, the violence until now has remained centered upon national policy grievances, linking a peripheral insurgency to urban mobilization and protest.

But with the overt attempt to capture territorial outposts in the attacks on 1-2 July and with the possibility that last Saturday’s plane crash was a deliberate attack on civilian targets, further support is given to Zack Gold’s assessment of a shift to sustained urban warfare (The Financial Times, 1 July 2015) and a possible internationalization of the conflict. Major General Mohamed Ali Belal commented on the intense two-week offensive conducted by the military that began on 6 September, saying that “a comprehensive campaign has been launched based on an estimation of the situation and fresh information about many hideouts and targets” (Al Ahram Online, 8 September 2015). This two-phase ‘Martyr’s Right’ operation sought to eliminate all militant threat from North Sinai and create conditions for infrastructural development in the peninsula. However, coupled with Major General Mohamed Ali Belal’s comments it seems to signal a more concentrated coordination between the Islamic State leadership and its regional partner in Egypt that has prompted serious engagement from the Egyptian military.

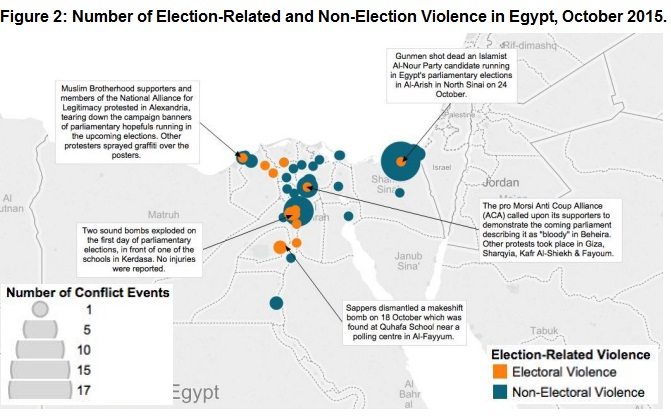

This month also saw the first round of Egypt’s parliamentary elections take place through 17-19 October, with a low turn-out of 26.56% in the first round (The Washington Post, 30 October 2015) and with violence surrounding the electoral process kept to a minimum. Minor episodes of violence were recorded in October with low-levels of protest held in large towns and cities by the pro-Morsi Anti-Coup Alliance (ACA) (see Figure 2). Other threats of election sabotage were dealt with swiftly and contained by security services, with 16% of all political violence in October related to the elections. Voter fatigue, lack of political competition and a complex voting system account for poor attendance and falling participation in the current elections, which may help elucidate why widespread electoral violence failed to proliferate. Numerous presidential, parliamentary and constitutional referendums since 2011 are believed to have worn voter enthusiasm for participation down.

With the success of the ‘For the Love of Egypt’ coalition in the first round of voting, it becomes evident that little has changed from the authoritarian electoral politics under Mubarak. The absence of parties competing on ideological platforms is indicative of that fact that “votes are not cast on the basis of political issues or party platforms but as a choice between competing personalities within a context of patron-client relations” (Zaki 1995: 101). ‘For the Love of Egypt’ coalition won all 60 seats in the first round of voting across 14 governorates, despite the fact that the 10 parties comprising it do not have a unified political philosophy. As a result, the closed party lists have enabled previous National Democratic Party (NDP) members and Mubarak-era candidates to secure nearly 30% of the seats (Egypt Independent, 29 October 2015).

The initial success of the pro-Sisi ‘For the Love of Egypt’ bloc confirms two features of Egyptian politics. Firstly, elections are far from providing a path to democracy, rather a carefully engineered return to managed rule that minimises political competition. Secondly, Egyptian politics has become increasingly de-politicised and impotent whilst at the same time growing ‘individualised’. This has seen traditional parliamentary roles being replaced by “business tycoons – who can either dip into their own pockets for payment of these expenses [distributing public services] or turn to vote buying with cash” (Blaydes, 2010: 108).

Furthermore, a large proportion of these individuals are ex-security officials, businessmen and wealthy, influential tycoons such as Naguib Sawiris – the founder of the Free Egyptians Party (FEP) – who, in the absence of ideology are able to offer services to constituents through their economic position. In Fayoum, and other areas long neglected by the central state, political influence through tribal affiliation remains strong and candidates are elected based on familial ties due to their perceived ability to secure vital infrastructure such as access to water or more job opportunities (Mada Masr, 20 October 2015). This localization of politics has served to de-politicise the electoral environment. Those elected through the individual list system are seen as the guarantors of much needed services, yet as a resident from Abshaway highlights “people choose the favored son of their village, but after elections we won’t ever see his face again” (Ibid.). Egyptian parties are thus lacking in ideology, service delivery or representation.

However, these turnout rates are not substantially different to those of 2008 and 2000, indicating that the role of elections in Egyptian life needs to be re-theorised to understand its performance, particularly in light of the traditional clientelistic transactions that feature in sub-Saharan African elections. Voters and constituencies are neither mobilizing on a large scale nor receiving substantial service delivery. Therefore, the idea of candidates as intermediaries between state and population, nor free-rider explanations capture the dynamics at play in Egypt. As Brownlee (2011) notes, Egypt may represent a case where non-electoral mechanisms of power are more pertinent. In which case, low turnout and apparent voter apathy should not be interpreted as a result of a moribund civilian base, rather an impotent and poorly institutionalized voting system.

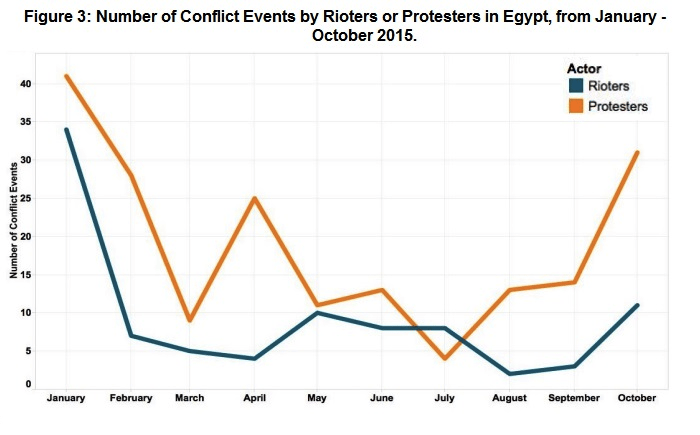

Thus, whilst immediate violence surrounding these elections has been contained, lack of electoral participation may not signal a decline in organized violence or protest in the coming months. Rather, the increasing number of protests over the past three months (Egypt Independent, 18 October 2015) (see Figure 3) may signal a shift in the rules of the game in which protests take a more central role through ‘politics by other means’.

This report was originally featured in the November ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.