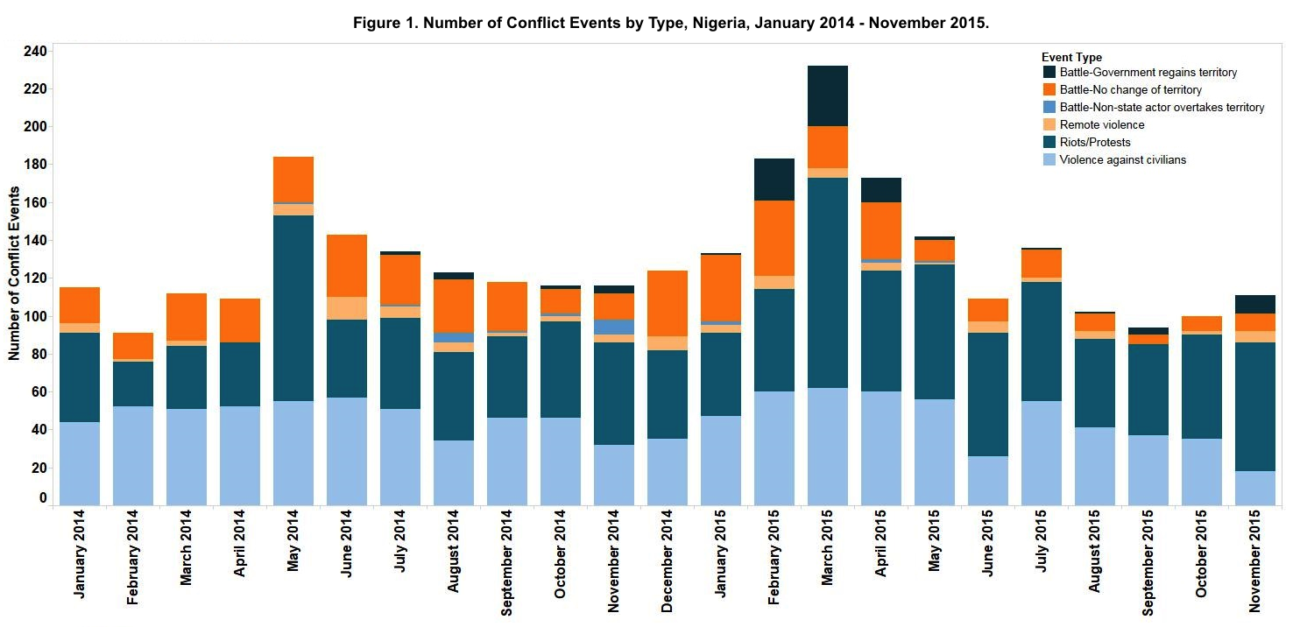

Nigeria was the second most active country in the ACLED dataset in 2015. The first few months of 2015 witnessed a front-loading of violence, with both a climax in conflict with Boko Haram and the Nigerian general elections. These events made the first quarter of 2015 the most violent in Nigeria in terms of both number of events and casualties since ACLED’s monitoring of the country began in 1997. Although the majority of this violence has focused on the conflict with Boko Haram, there have been considerable violent and non-violent (protests) from civilians throughout the year, and in March in particular (see Figure 1).

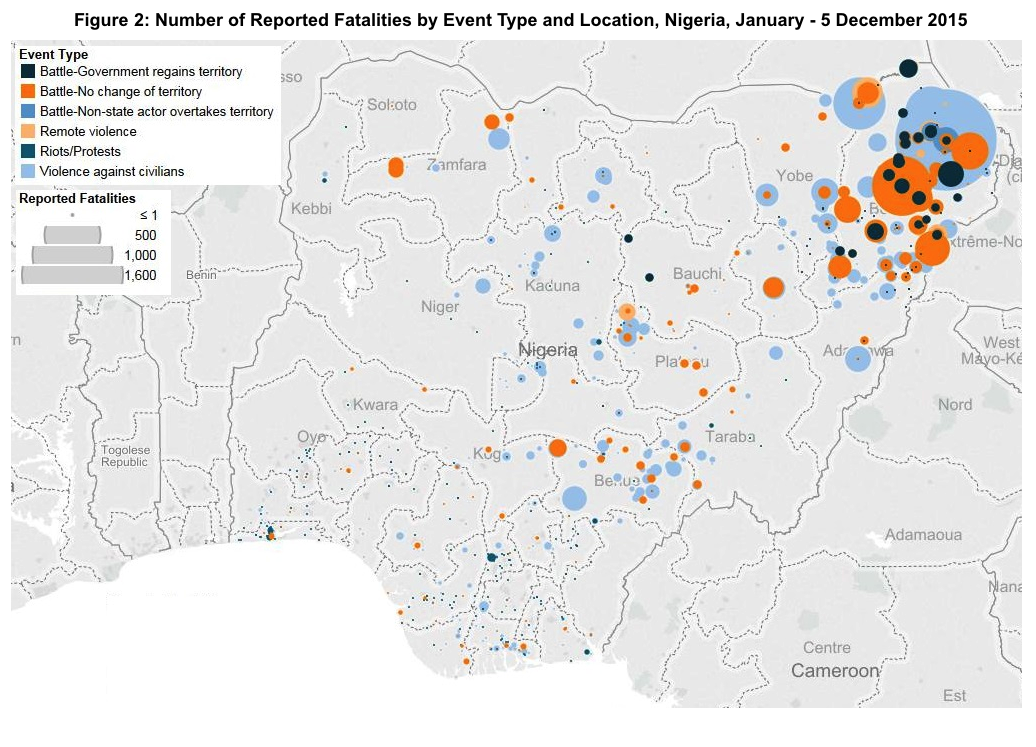

The interconnectedness of the 2015 general election with Boko Haram’s conflict with the Nigerian government is of particular note for Nigeria. Starting in late 2014, Boko Haram’s ability to take and hold territory led to increasing attacks throughout Nigeria, although the preponderance of these incidents occurred in Borno State and the three northeastern states of Adamawa, Gombe and Yobe (see Figure 2). The militant group also staged attacks in the neighbouring states of Cameroon, Chad and Niger. However, Boko Haram’s single most dramatic attack was the January 2015 Baga massacre, which is believed to have resulted in as many as 2,000 fatalities (see Figure 2). Besides the extraordinary number of fatalities, the attack was particularly audacious as Baga was the headquarters of the Multinational Joint Task Force which was made up of troops from Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria (BBC News – Africa, 2 February 2015). Furthermore, President Goodluck Jonathan had just made a pledge to defeat Boko Haram in his new year’s address (BBC News – Africa, 1 January 2015).

This attack played a major role in catalysing a joint offensive agreed to by Nigeria, which saw the intervention of Chadian and Nigerien, and later Cameroonian, troops into the conflict (Daily Post, 23 January 2015). The multinational offensive began in mid-February and until May the multinational forces managed to take back a considerable amount of territory from Boko Haram (see Figure 1), successfully isolating them to a relatively small area surrounding the Sambisa Forest (The Nigerian Observer, 2 June 2015). Despite their early successes however, a lower level of fighting has continued since April. On the other hand, violence against civilians has seen a consistent downward trend since the height of the conflict with Boko Haram in March (see Figure 1), while instances of remote violence have stayed relatively consistent.

Amidst the struggle against Boko Haram militants, Nigeria also held its general election, which was significant affected by the ongoing conflict. Most notably, the election was postponed from February 14 to March 28 in order to allow the government’s offensive time to secure the north-eastern states to enable effective participation in the voting (The Guardian, 7 February 2015). On March 27, one day before the election, the military declared that virtually all territory held by Boko Haram had been recaptured (BBC News – Africa, 27 March 2015). Whilst voting was largely able to go ahead in the northeast, Jonathan Goodluck’s PDP government was still defeated in the polls by Muhammadu Buhari’s APC party.

Although the largely peaceful handover of power from President Goodluck to Buhari was historic for Nigeria, the election itself was marred by considerable violence. This took various forms, including Boko Haram attacks both before and during the election, political parties rioting and engaging in violence against civilians, and others involved in incidents of violence conducted at polling stations and/or related to the general election more broadly. Combined with those leading up to the election, these events played a role in making the number of riots and protests recorded in March significantly high in Nigeria’s recent history (see Figure 1).

Despite the Nigerian military’s continued conflict with Boko Haram and the militant group’s sustained violence against civilians, by September Nigeria had seen an overall drop in violence. Violence decreased to levels not seen since February 2014, with around 94 violent incidents as compared to the high of 232 in March 2015 (see Figure 1). Even more dramatically, by November 2015 the fatality levels recorded by ACLED had dropped to a low not seen since February 2013, with around 230 fatalities recorded compared to a high of over 3,000 in January 2015.

Looking forward to 2016, there are a few key trends to monitor. The first is the prospect of a continued decrease in overall violence. Boko Haram was the single most violent conflict agent in 2015, but as the military continues to be largely successful in its battle with Boko Haram (IBT, 20 September 2015), its role may diminish. However, the militant group has continued to carry out sporadic suicide bombings and other violence against civilians (Daily Mail, 6 December 2015). A second trend to watch out for is the increasing number of protests by groups espousing Biafran independence (IBT, 17 November 2015). During the election, the potential for renewed instability in the Niger Delta was a concern raised by various groups (The Guardian, 11 March 2015), and more recently organizations such as the International Crisis Group have warned that it may “erupt into violence again” due to “long-simmering grievances” (Premium Times, 7 October 2015). If it does, this longstanding issue could become the newest driver of conflict in Nigeria.

This report was originally featured in the December ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.