A look back at political conflict across the African continent this past year yields a number of trends and unexpected developments. Leaders have sought to extend constitutional term limits to remain in power – leading to demonstrations and conflict within states. Relatedly, coups d’état – or attempts thereof – have occurred, in large part as a response to leaders who have sought to remain in power. And refugees continue to be an issue on the continent and on a global scale.

Term Limit Extensions

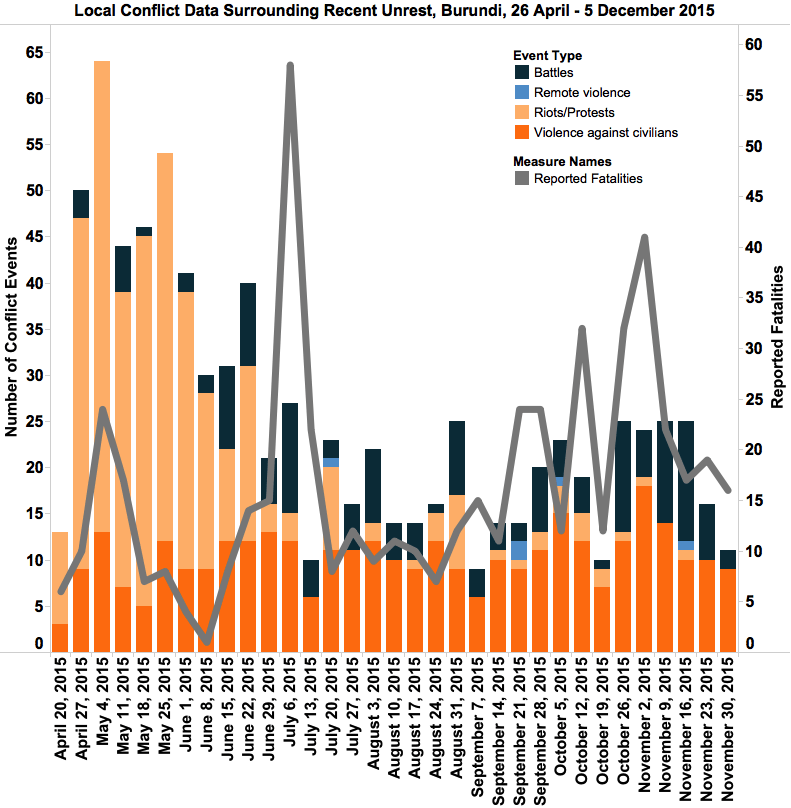

While numerous African countries with constitutional term limits have contemplated the removal of these limits in the past two decades (African Leadership Centre, 2015), this past year has seen a number of these attempts play out (Mail and Guardian, 18 July 2015). Many confronted with backlash. In April, President Nkurunziza of Burundi announced his bid for a third term as president, despite the constitution explicitly stating that a president can serve only two terms (BBC, 25 April 2015). This move was met with hundreds of protests and much opposition (The Guardian, 26 April 2015). Elections have since been held (though were disputed, and boycotted by opposition groups), and Nkurunziza remains president (Al Jazeera, 25 July 2015). Opposition however ensues and has been met with much violence. While riots and protests dominated political conflict in Burundi in the months following April, political violence has since shifted to battles between the police and opposition groups wielding weapons as well as instances of violence against civilians; unsurprisingly, this shift in conflict dynamics has also been accompanied by a higher rate of reported fatalities (ACLED Crisis Blog, 8 December 2015). In recent months, many activists and human rights leaders have been targeted, and a crackdown on media has hindered much of the ability to receive timely reports of the violence on the ground (see ACLED Crisis Blog, 1 December 2015). Figure 1 below depicts local-level conflict in Burundi, using both media reports as well as relying on crowd-sourced information to gain a clearer picture of what is occurring on the ground.

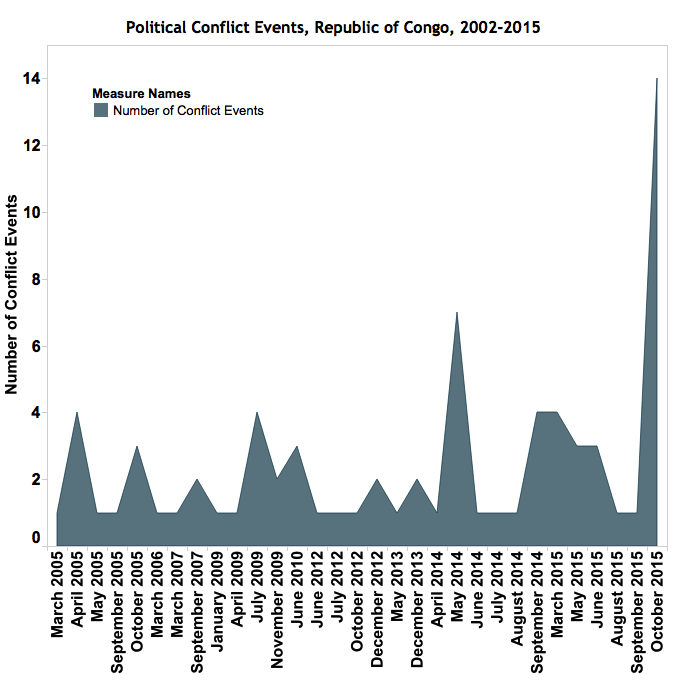

Other leaders have sought extensions to their terms as well. In Rwanda, the effort met with almost no opposition – 99% of Rwandan lawmakers voted for changes to the constitution to allow President Kagame to extend his 15 years in power (Mail and Guardian Africa, 14 July 2015). Yet, in the Republic of Congo, there was significant resistance. In September, President Nguesso of the Congo announced that a constitutional referendum would take place in order to allow for him to seek re-election (Daily Nation, 6 October 2015). In response, October became one of the most violent months in the Congo in over a decade (see ACLED Crisis Blog, 5 November 2015). Figure 2 below depicts trends in conflict in Congo-Brazzaville since 2002.

Whether President Kabila of the Democratic Republic of the Congo will step down at the end of his second term this month, or whether he will seek to alter the constitution like so many of his African peers in order to extend his time in power (Foreign Policy, 28 July 2015), is still to be seen. His attempts at delaying the upcoming elections, however, raise worry (Allaire and Titeca, 3 December 2015).

Coups d’Etat

Relatedly, coups d’état have been attempted, especially in response to efforts at extending presidential term limits. In May, General Niyombare led an attempted military coup in Burundi in opposition to the president’s seeking an additional term in office (BBC, 13 May 2015). The attempt was subsequently foiled (CNN, 19 May 2015), and has ultimately exacerbated government crackdown in response to opposition to Nkurunziza’s bid (BBC, 16 May 2015).

Late last year, then-President Compaoré of Burkina Faso sought to alter the constitution in order to extend his already 27-year rule (Opalo, 28 October 2014); Compaoré became president in 1987 after leading a successful coup d’état during which then-President Sankara was killed. Unsurprisingly, Compaoré’s attempts at extending his time in office were met with opposition, demonstrations, and violence, including the parliament building being set on fire (Brookings, 30 October 2014). As a result, a transitional government came into power in November 2014.

In September 2015, shortly before elections were set to occur, the Presidential Security Regiment (RSP), an elite unit within the Burkinabé army, led by General Diendéré, staged a coup to dissolve this transitional government, holding the transitional president and prime minister hostage (ACLED Crisis Blog, 9 October 2015). After a week in power, Diendéré stepped aside, and transitional-President Kafando was reinstated. Some argue that “the proximate cause for the upheaval … [was] presidential power and term limits [as] Mr. Diendéré is a close ally of the former president, Blaise Compaoré,” who sought to extend his term limit in late 2014 (The Economist, 18 September 2015). The close relationship between Diendéré and Compaoré was further highlighted earlier this week with Diendéré being charged with complicity in the killing of ex-President Sankara in 1987 during the coup that resulted in Compaoré’s becoming president (Associated Press, 6, December 2015). More recently, President Kaboré has succeeded transitional-President Kafando in office; he was elected late last month as the country’s first new president in decades (Al Jazeera, 29 November 2015).

Refugee Crises

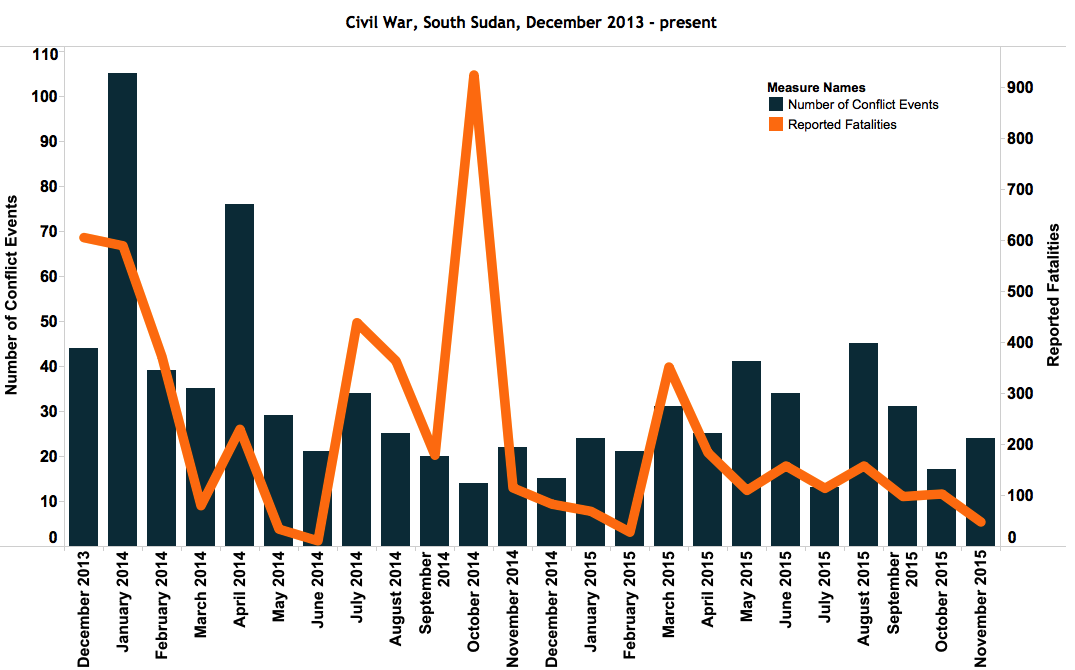

Refugees continue to be a pressing issue across the continent. The UNHCR announced earlier this year that continued conflict in South Sudan has pushed the numbers of refugee and internally displaced people (IDPs) ever higher (UNHCR, 7 July 2015), with reportedly over 2.2 million displaced people (CNN, 29 October 2015). The civil war in South Sudan began in December 2013, pitting the opposition forces of former Vice President Machar against President Kiir’s government forces. Despite numerous peace talks and negotiations – as well as international mediation attempts and a number of failed ceasefire agreements – the conflict has continued. Mass graves, rape and sexual violence, as well as forced cannibalism are among the atrocities reported as a result of the crisis (Al Jazeera, 28 October 2015). Figure 3 below depicts this ongoing conflict since December 2013. While there have been reports that the influx of South Sudanese refugees to Ethiopia has declined (Government of Ethiopia, 16 November 2015), President Kiir states that South Sudan is struggling to resettle thousands of refugees and IDPs (Reuters, 18 November 2015).

The refugee crisis has spanned beyond African borders as well. While the largest groups seeking refuge in Europe this year, risking their lives to cross the Mediterranean, have been Syrians and Afghans, the third largest group has been Eritreans (Amnesty International, 2 December 2015). “Tens of thousands of Eritreans have arrived at Europe’s shores in recent years seeking asylum” (Council on Foreign Relations, 11 November 2015). Eritrea’s refugee population totals to about half a million people, with approximately 5,000 people leaving the country each month (Council on Foreign Relations, 11 November 2015). For a country of only about 4.5 million people, this number is especially large, making Eritrea “one of the world’s fastest-emptying nations” (Wall Street Journal, 20 October 2015).

Eritrea is accused of being a secretive dictatorship. There is no current independent media in Eritrea and a complete lack of freedom of the press, resulting in Eritrea topping the list of most censored countries (Committee to Protect Journalists, 10 April 2015). There is neither a functioning legislature nor any civil society organizations, resulting in a “dismal human rights situation” (Human Rights Watch, 2015). The UN has accused the government of extrajudicial executions and torture amongst other human rights abuses (The Guardian, 8 June 2015).

Many (especially young adults) are seeking asylum outside of Eritrea in order to flee national service. While officials claim that conscription would be limited to 18 months, “national service continues to be indefinite, often lasting for decades. Conscripts include boys and girls as young as 16 as well as the elderly and conscription often amounts to forced labour” (Amnesty International, 1 December 2015). Eritrea claims it has “no other choice” but to continue with the conscriptions “given the threat from long-standing enemy Ethiopia” (Agence France Presse, 2 December 2015).

As 2015 comes to a close, it remains unseen if and how these crises will see resolution or if these trends will continue in the coming year, though given the scale and nature of many of these crises, they are likely to continue. Despite the unexpected nature of some of these developments, the occurrence of similar trends elsewhere on the continent is telling of how similar institutions and mechanisms can yield analogous results across countries.

This report was originally featured in the December ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.