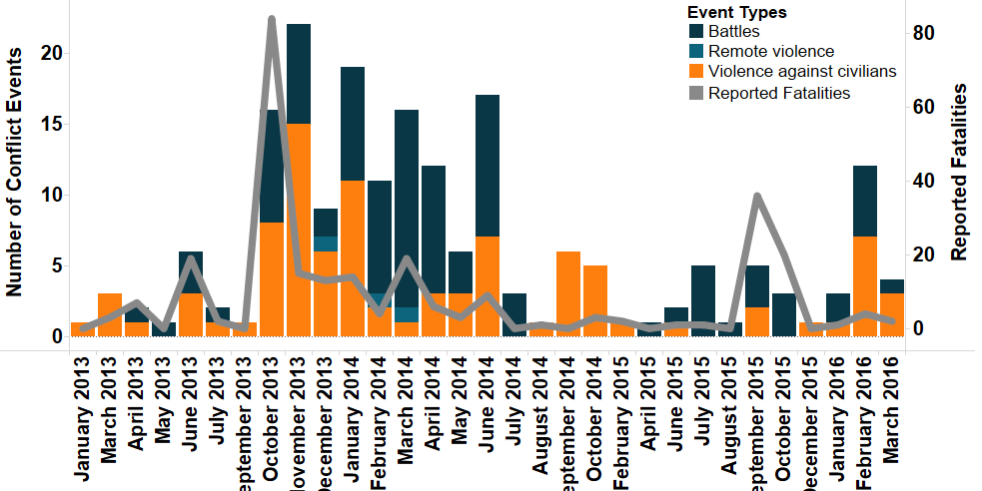

Over the past few months, Mozambique has witnessed escalating tensions between the Mozambican National Resistance movement (RENAMO) and government forces. Following a series of army operations aimed at disarming RENAMO’s militias in late 2015, violence has resurfaced in the first three months of 2016. With twelve distinct incidents of political violence, the month of February saw the highest number of reported conflict events since June 2014 (see Figure 1).

In 2016, RENAMO engaged in several armed clashes with government troops. On the 17th of February, an attack on a police post in Sofala province resulted in the death of one officer and one RENAMO militant (AllAfrica, 17 February 2016). Other incidents occurred in the neighbouring provinces of Manica and Tete, two RENAMO strongholds in the north of the country, and in the southern town of Mazivila, where a group of five rebels assaulted a police station in a failed attempt of seizing weapons (AllAfrica, 22 February 2016).

Fighting in northern Mozambique has also fed renewed violence against the civilian population. In a worrying episode of factional violence, six RENAMO militants killed an official of the ruling Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) in his house in Nhamatanda (AllAfrica, 16 February 2016). In a separate incident, suspected police injured RENAMO’s secretary-general Manuel Bissopo and killed his bodyguard in an attempted assassination in the central coastal town of Beira (Africa Confidential, 18 March 2016). The first quarter of 2016 saw five civilian fatalities, the highest number reported by ACLED since the beginning of the insurgency in 2013.

Protracted insecurity and allegedly widespread army abuses in northern Mozambique, together with a severe drought, prompted a major refugee crisis, with more than 12,000 people reportedly fleeing into neighbouring Malawi (International Business Times, 16 March 2016). Human rights organisations accused the Mozambican armed forces of carrying out forced disappearances and summary executions during disarmament operations in rebel-controlled areas (Human Rights Watch, 22 February 2016; Times Live, 22 March 2016). Government officials of both Mozambique and Malawi have denied that the displaced persons pouring over the border can be granted refugee status, and are jointly working on repatriation. Nevertheless, the deteriorating situation in northern Mozambique and across the border with Malawi raise concerns internationally, and the UNHCR has called both countries to take action in order to safeguard the rights of the Mozambican asylum-seekers.

The proximate causes of this recent wave of fighting lie in the increasing political isolation of RENAMO and of its leader Afonso Dhlakama after the 2014 elections. RENAMO’s historical leader accused FRELIMO of vote rigging and rejected the electoral outcome, despite the increasing number of seats gained by his party in the legislative branch (Africa Confidential, 7 November 2014). Hostilities between FRELIMO and RENAMO peaked in March 2015, when Dhlakama declared that six central and northern provinces, including Manica, Sofala, Tete, Zambezia, Nampula and Niassa “shall be governed by RENAMO” (International Business Times, 1 March 2016).

FRELIMO’s position over the possible reopening of negotiations with RENAMO has wavered under the presidency of Filipe Nyusi, who took office in January 2015. Whereas his predecessor Armando Guebuza advocates an uncompromising stance, Nyusi has formally expressed his support for holding talks and ending the conflict with RENAMO (Africa Confidential, 18 March 2016). However, while Dhlakama has agreed to drop his claim on the six provinces and return to the negotiating table with the South African president Jacob Zuma, the Vatican and the European Union acting as mediators, Nyusi restated his preference for bilateral negotiations, thus prolonging the stalemate. Furthermore, internal opposition loyal to Guebuza and the attempted killings of Dhlakama and Manuel Bissopo have posed further obstacles to the negotiation process, and thus far prevented official talks from taking place (African Arguments, 15 February 2016).

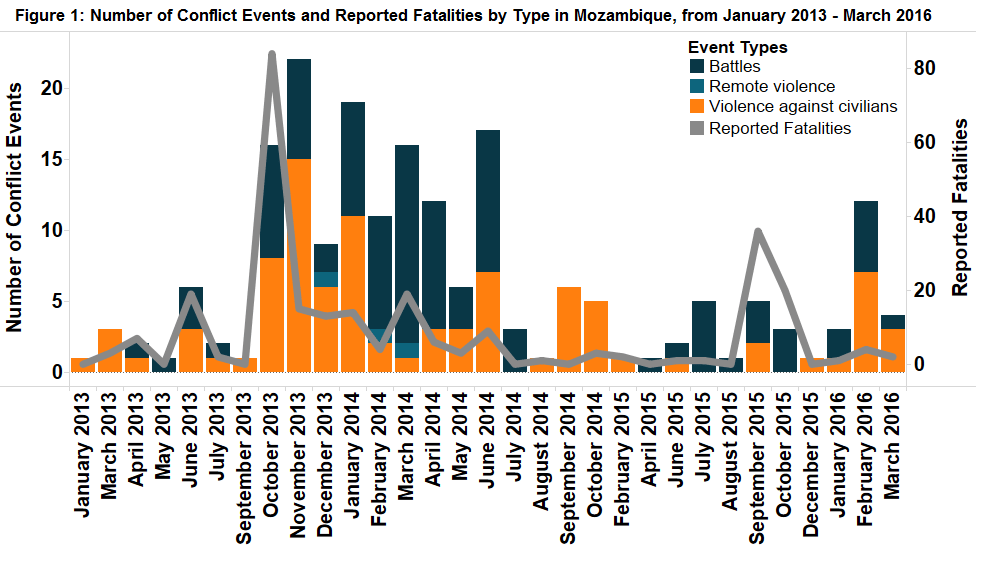

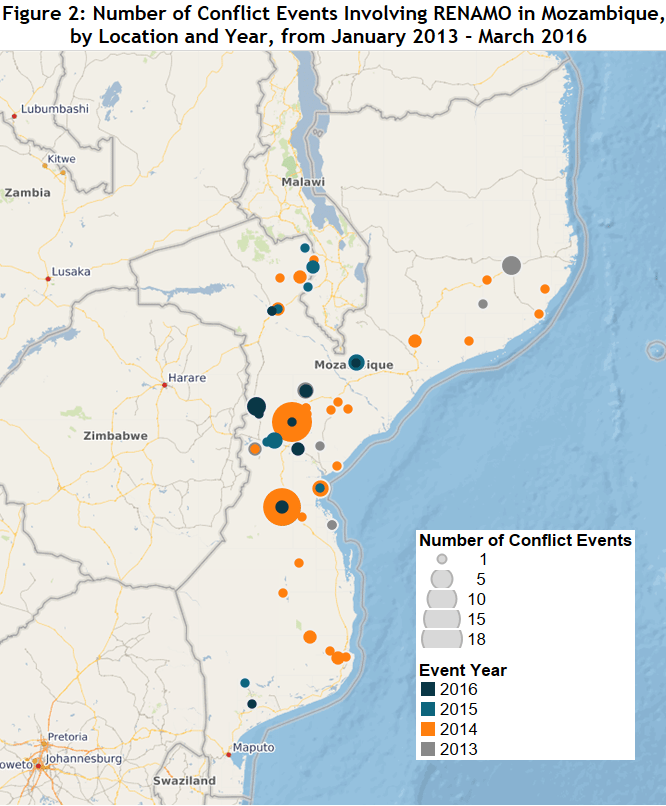

RENAMO’s conflict activity has concentrated mostly in Mozambique’s central and northern areas, which correspond to the provinces previously claimed by Dhlakama and constitute the party’s traditional power base. The map in Figure 2 also shows that violent events involving RENAMO’s militias clustered around the country’s main communication routes, where the rebels have set up armed roadblocks and checkpoints. RENAMO’s militias were held responsible for several ambushes on civilian vehicles along the main north-south highways, including an attack on a bus that caused the death of two people in Manica province in March (International Business Times, 7 March 2016).

The particular geographical distribution of conflict events highlights the strategic importance of the N1 and N7 roads, which, passing through Mozambique, represent a vital infrastructure connecting the resource-rich north with the south of the country. Whilst the prospects of a large-scale insurgency appear remote due to the limited military capabilities of RENAMO and the reluctance of its leadership – which would rather prefer a compromise with FRELIMO (Africa Confidential, 18 January 2016) – these sporadic attacks on the country’s main thoroughfares may still harm the national economy, and point to RENAMO’s attempt of influencing the political process.

These mounting tensions leave the country in a state of uncertainty. One of Africa’s fastest growing economies, Mozambique risks losing trust of foreign donors and undermining its positive economic outlook should this situation continue. Debt distress – which has severely weakened the country’s economy in the past – might still hamper growth in the future. Much of Mozambique’s future prospects thus relies on whether the ruling FRELIMO and the opposition RENAMO will be able to settle their differences peacefully and agree on a shared political roadmap.

This report was originally featured in the April ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.

Authors: Andrea Carboni and Aurora Leo.