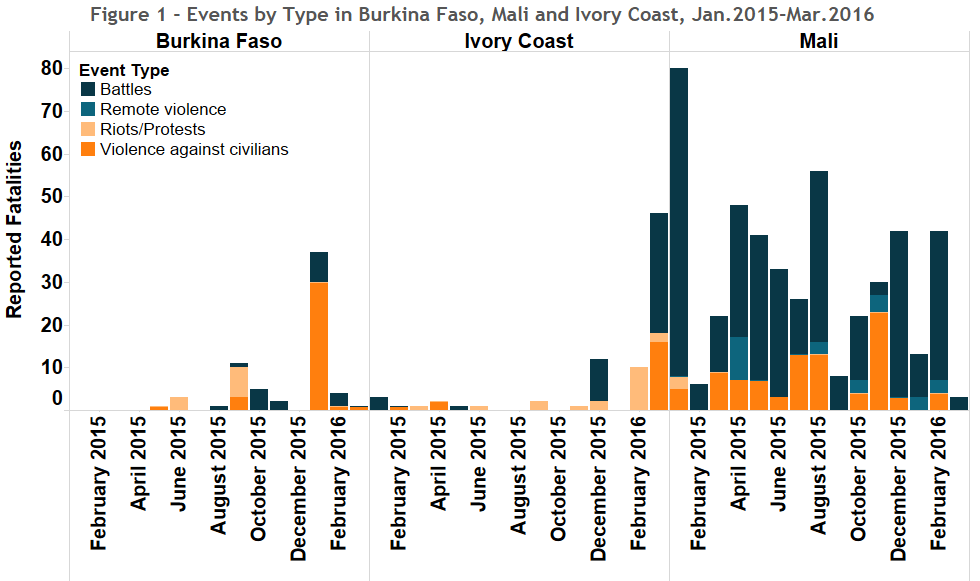

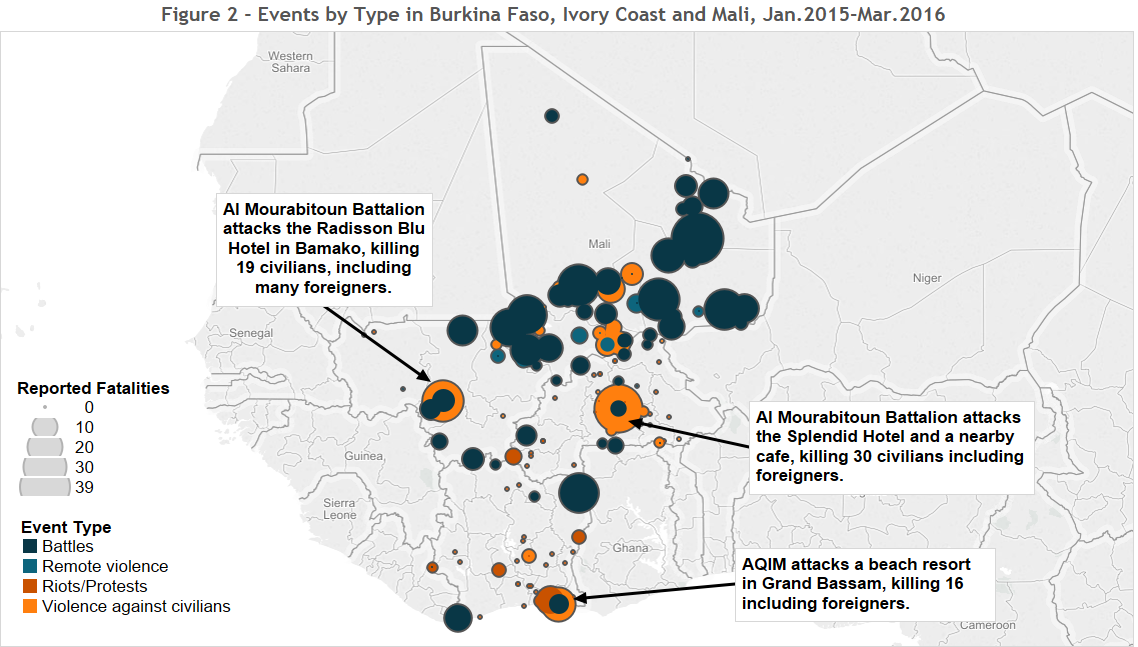

Attacks by militants aligned with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), notably the Al Mourabitoun Battalion, in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali have caught international headlines in the past few months due to their high fatality counts and targeting of foreigners. The attack on the Splendid Hotel/Cappuccino Café which killed at least 30 in Burkina Faso’s capital of Ouagadougou in January (Wall Street Journal, 17 January 2016), and the attack on a popular beachside resort which killed at least 16 in the Ivory Coast town of Grand Bassam in March (Guardian, 13 March 2016) are particularly notable as they occurred in countries which have not previously seen such large-scale violence from these groups. This is in contrast to Mali, which has seen many instances of violence against civilians carried out by militants in its northern provinces. These include an attack on a nightclub frequented by foreigners in the capital Bamako in March 2015, and the November assault on Bamako’s Radisson Blu Hotel killing 19 (VOA, 23 November 2015). When taking account of fatalities among the perpetrators, the three attacks in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali are all the more notable, given that they constitute the deadliest events recorded by ACLED in these countries since the beginning of 2015 (see Figure 1).

In total, Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast had less than 10 reported fatalities from violence against civilians in 2015. On the other hand, Mali – which is still dealing with the fallout of its 2012 civil war and the associated rise in militancy in the country – had 68 fatalities excluding the 19 from the Radisson Blu attack (see Figure 1). Focusing on Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast specifically, violence patterns hold two important insights: first, attacks of this type are extraordinary in these countries and have raised concerns about the abilities of security services to deal with them in the future (Independent, 23 November 2015). Second, the success of these attacks will likely embolden militants in general, and AQIM in particular, to plan further attacks in the future. Mali has experienced higher levels of violence against civilians relative to the other countries examined in this report, but even in its post-conflict context, only one other high fatality violence against civilians event (i.e. at least 10 deaths) occurred, and is related to inter-communal conflict. The three attacks in Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Mali have meant that AQIM, with the help of the Al Mourabitoun Battalion, has established itself as the deadliest militant group in terms of civilian fatalities in West Africa outside of Boko Haram (see Figure 2).

The fact that AQIM was able to engage in these attacks outside of its traditional zone of operation should also highlight the potential threat of future attacks across the region. AQIM has shown that it is now comfortable striking outside of the trans-Saharan regions of the Sahel and Maghreb, which is the group’s main areas of operation in the past. The geographical expansion of attacks can also be seen as having a demonstrative impact on AQIM’s rivals, such as the Islamic State (IS) and Boko Haram (which has sworn allegiance to IS), as well as potential recruits (AllAfrica, 4 February 2016), as the group shows that it is able to strike targets previously thought to be out of the reach of militant groups.

Although occurring in a different context, these West African attacks can be said to parallel those over the past few months in Paris and Belgium, whereby IS has displayed its capability in coordinating international attacks. The justifications given by both IS and AQIM parallel each other, with both claiming their attacks were aimed against the French due to their respective military actions against the groups, with IS referring to Syria (Vox, 14 November 2015) and AQIM referring to French deployments in West Africa under Operation Serval (Quartz Africa, 16 March 2016).

Just as there are fears in Europe that IS could strike elsewhere following the attacks in Brussels, other West African countries are feeling equally threatened in the wake of the Bamako, Grand Bassam, and Ouagadougou attacks. Countries such as Senegal and Mauritania feel vulnerable to future attacks (Mail & Guardian, 14 February 2016) and have responded to threats accordingly. In Senegal for example, over 500 people were reportedly detained in a ‘terrorist’ crackdown in January (Telegraph, 27 January 2016). In the same month, suspected AQIM activists of Guinea-Bissau nationality were detained in Guinea while traveling with a Mauritanian fugitive and senior AQIM member wanted in connection with a plot to assassinate the Mauritanian president in 2011 (Reuters, 21 January 2016).

The possibility that militant networks might manage to make the jump from the Saharan borderlands of West Africa all the way to its southern and western coasts has for many years been recognized to be a serious threat to regional security (Al Jazeera, 24 June 2013). But with the reality now established, the question of having the capacity to deal with this threat will now become a key priority.

This report was originally featured in the April ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.