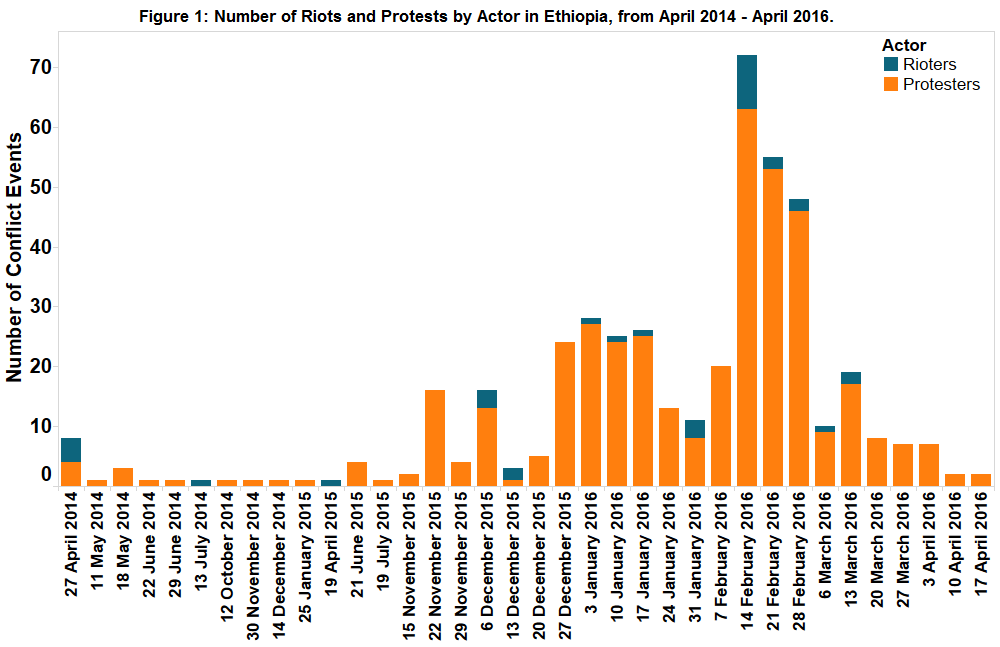

Since the beginning of March 2016, protests in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia have sharply declined. From November 2015 – February 2016, an average of 23 protests were recorded per week as protesters mobilised against the planned expansion of the Addis Ababa administrative region which threatened to displace Oromo farmers. On 12 January the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO) announced that the ‘Master Plan’ will be put on hold (HRW, 15 January 2016; ACLED March 2016). Despite this concession, protests escalated to unprecedented levels in February 2016 as distrust prevailed amongst protest communities. However, since March, protests have been subject to a drop off with an average of 8 protests per week (see Figure 1).

A melting pot of grievances has been used to understand the most recent wave of protests, but two features of the Oromia protests challenge contemporary understandings of protest dynamics. First, the timing of protests and second, the power of unorganised protests to achieve their stated goals. This report considers both of these features by situating protest within the structural environment in which it takes place, as well as in relation to broader regional issues that impact the state’s capacity to respond.

In terms of timing, similar government actions to extend Addis Ababa and displace the people of Oromia under the pretext of development have occurred since 2005. Since 2005, forced evictions and urban land-grabbing escalated after two opposition groups – the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD) and the Union of Ethiopian Democratic Forces (UEDF) – won 174 seats, or 32% of the vote for the Ethiopian Parliament (VOA, 16 May 2010). In 2014, similar protests erupted on a smaller scale after the Ethiopian government first announced its plans for development and growth. From this stance, fears “that Oromian farmers will be evicted from their lands without compensation and that the cultural and linguistic identity of the area surrounding Addis will be obliterated” (Africa Confidential, 7 May 2014) have prevailed for over a decade.

Given the historical marginalisation of the Oromia region and that “Oromo resentment of the capital’s expansion has been building for years” (Africa Confidential, 18 March 2016), grievances alone lack the explanatory power in determining the latest eruption of protest. Instead, the configuration of Ethiopia’s federal system offers insight into the proliferation of protests. The micromanagement of the federal regions, including Oromia region, through a highly centralised state apparatus has removed any territorial autonomy defined in the 1995 Constitution. The imposition of the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO) as an “administrative representative of TPLF in Oromia region, but not the political representative of Oromo people,” (IBTimes, 14 January 2016) smothers the ability of Oromo people to voice their historical grievances. Furthermore, by acting as a puppet of the state (Ethiopian Human Rights Project, March 2016), OPDO has failed to adequately represent and backchannel the localised demands of the Oromia region.

Hence, the current wave of protest is the result of a governance blackspot. The severe lack of public consultation on state developmentalism and absence of a platform for the voices of Oromo to be heard have led to an unexpected local expression of grievance.

The second feature of the protests is the absence of civil society organisations in leading the protests. Despite this, non-organised groups have demonstrated their ability to exact concessions from the state. Protests first erupted on university campuses in Ambo in April 2014 and in the subsequent protest waves (November 2015 and January 2016) farmers and civilians then took the lead. The spread of protests has also been characterised by a noticeable absence of civil society organisations or local representation as negative sentiment towards OPDO runs high. It is difficult therefore to establish a connection between civil society involvement and the success of protest demands. All of this challenges received wisdom on protest dynamics and formal organisation and calls for renewed attention into the trajectories of ‘unorganised’ protest movements.

The interaction between government and protesters may hold key insight into the latent power of protest movements. The EPRDF’s response may draw attention to wider regional dynamics that have influenced or constricted its ability to deal with the protest outright, thereby strengthening the position of the protesters. Leading up to the concession, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn found himself between a rock and a hard place. Two such regional dynamics include balancing the demands of the Tigray elite who tie Deslaegn’s hands in their push for greater economic expansion, and addressing the worst drought in 30 years. “Some suggest that he [Hailemariam] is a mere figurehead and that real power is still within a core TPLF group shadowing him” (Huffington Post, 21 December 2015). Here it is worth investigating how these interact to produce the trends observed. Amidst accusations that food aid has been distributed along partisan lines (Counterpunch, 8 January 2016), it is feasible that large portions of the $192 million allocated for aid relief in the on-going drought is being directed towards the Tigray region in order to placate hardline Tigrayan’s pushing for a harsh response to unrest in Oromia.

Both of these are likely to have affected Desalegn’s strategic calculation of the potential power of the Oromia protest movement to capitalise on other regional issues at the time. The temporary back down on the Master Plan therefore reflects how the EPRDF positions itself and its interests against concurrent issues in Ethiopia and offers fresh insight into analysing protest dynamics. In this case it demonstrates an attempt to contain further confrontation as protests continued unabated in the face of worsening state repression.

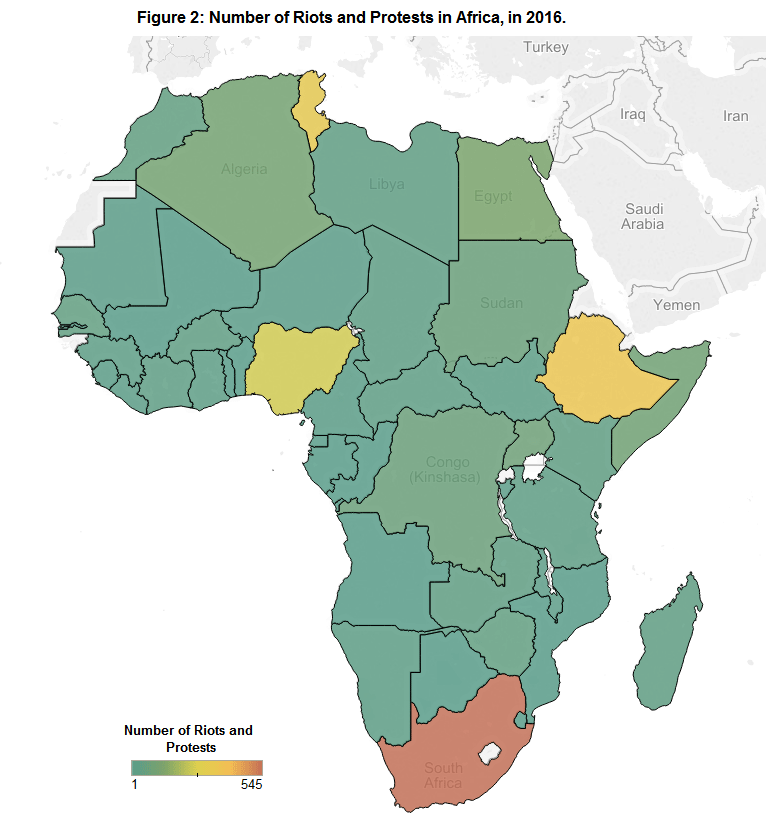

The Oromia protest movement raises a number of questions in larger literature on protest success, dynamics, trajectories and escalation. Investigating the goals and challenges of African regimes and how they interact with non-state groups may provide better understanding of the specific developments witnessed in current protest dynamics across the continent including Tunisia, Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt (see Figure 2).

This report was originally featured in the May ACLED-Africa Conflict Trends Report.