More than two decades after civil war ended in Mozambique, and despite years of economic growth and relatively peaceful elections, the country continues to face political and security challenges.

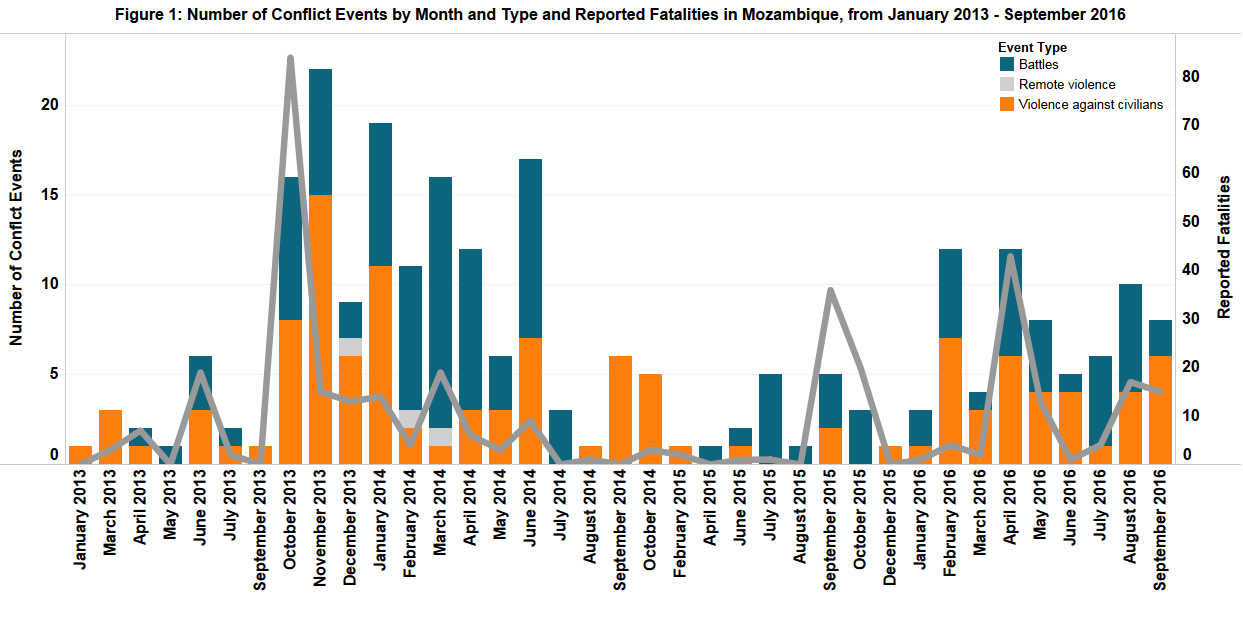

General levels of political violence have continued to rise in 2016 as events have increased in intensity and in geography (68 events of political violence across 10 provinces have been recorded in 2016 up from 19 such events were observed across 6 provinces in 2015). Among these events, violence against civilians has risen sevenfold, representing the largest shift from an initially low rate. Fatalities have reached their highest levels since 2013, and fatalities from violence against civilians have doubled compared to their highest levels in the past two decades (see Figure 1). Civilians are increasingly bearing the brunt of the clashes between RENAMO and the government. In addition to significantly higher fatalities, thousands of people have already fled the country, and access to health for tens of thousands of people in remote areas of the country is threatened by RENAMO attacks on medical facilities (HRW, 6 August 2016).

Political violence in Mozambique in 2016 has been driven for the most part by tensions between the Mozambican National Resistance Movement (RENAMO) and government forces. Competition between both grew after a stalemate in their negotiations concerning two main tensions: the perceived non-fulfilment of core clauses in the 2014 ceasefire deal reached between the two groups, particularly the reintegration of RENAMO forces into state forces and the support to economic and social reintegration of demobilized forces (IPI, 22 June 2016); and the attempt by RENAMO’s leader Dhaklama to seize power in six regions he claims were won by his party in the last election (ISS, 15 July 2016; ACLED Crisis Blog, April 2016). The strategy on both sides between the talks appears to be demonstrating one’s capabilities to retain credibility and to weaken the other side’s bargaining position at the negotiation table. Negotiations have been President Nyusi’s official policy towards RENAMO since 2015, but they have reached several deadlocks. For instance, in March 2016, due to inflexibility on both sides, the talks were “indefinitely postponed” by mediators. When they resumed in August, they reached a new stalemate over a temporary ceasefire that would allow mediators to go to Dhlakama’s base in Gorongosa (The Open University, 25 August 2016).

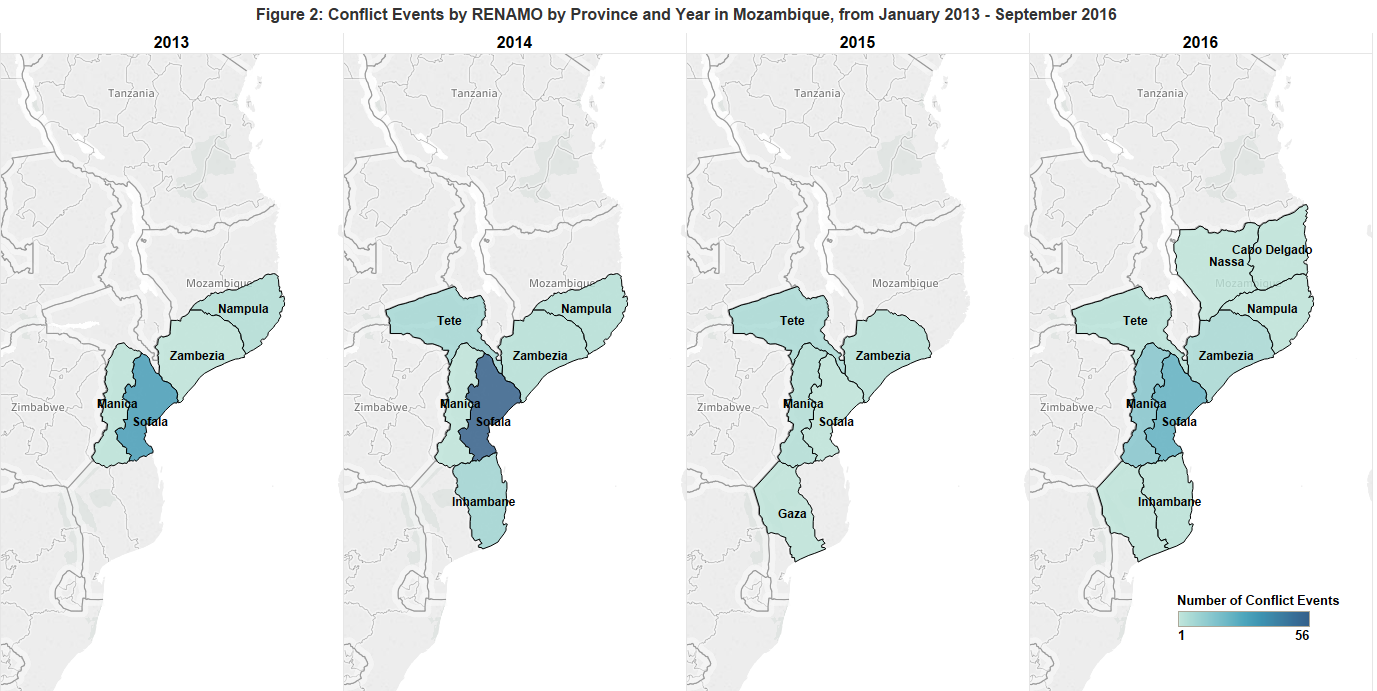

In 2016, RENAMO’s attacks spread to provinces where it had rarely or never carried out attacks since 2013, such as Nassa, Cabo Delgado and Inhambane (see Figure 2). This is believed to reflect a military strategy aimed at forcing the government to spread out troops across the country and reduce its concentration near Dhlakama’s base in Gorongosa (The Open University, 21 August 2016). Additionally, after the 1 April ultimatum to have the six provinces transferred to its authority passed without being granted, the group’s strategy and campaign was seemingly extended to target government resources and weaken the economy (Voa Portugues, 30 March 2016; IPI, 22 June 2016). Dozens of commercial trucks and trains were ambushed on main highways and railways in Sofala, Manica and Zambezia provinces, including when they were escorted in military convoys. For example, RENAMO gunmen attacked trains belonging to the Brazilian Company Vale on three occasions in June and July in Sofala (Lusa, 26 July 2016). These attacks are believed to put a significant strain on the largely import-dependent economy as military convoys have been criticized for not being frequent or fast enough to support it (AFP, 19 June 2016). RENAMO gunmen also repeatedly raided entire villages in Zambezia, Nassa, Manica, Sofala and Tete provinces, each time targeting health units and local government and police posts, stealing dozens of goods and damaging property (Agencia de Informacao Mocambique, 31 July 2016; Human Rights Watch, 24 August 2016).

Additionally, there has been evidence of mounting violence towards RENAMO as well as towards people suspected of supporting the group (Africa Confidential, 22 January 2016); (Africa Confidential, 27 May 2016; The Open University, 21 August 2016). In particular, government forces have been accused of committing summary executions, looting, destruction of property, rape and other human rights violations in its campaign to disarm RENAMO fighters (UN Human Rights Council, 29 April 2016; HRW, February 2016). In April, reports of a mass grave containing 120 bodies came out in a region that saw important clashes between security forces and RENAMO members in October 2015; however, local and provincial authorities denied the existence of the grave. The results of their investigations launched in June are yet to be announced (HRW, 6 August 2016). There have also been at least three attacks by unidentified assailants on RENAMO officials in 2016: in the latest event, a senior official was killed on 22 September in Tete province (Agencia de Informacao Mocambique, 23 September 2016).

These attacks come against a backdrop of rising repression, with human rights defenders having reportedly been harassed and threatened for calling for demonstrations in favor of accountability and transparency in the management of public resources, and with the announcement by the Head of Police in April that any public protest would be repressed (UN Human Rights Council, 29 April 2016). All of these elements appear as signs that Nyusi might have become frustrated with the deadlocks reached in the negotiations with RENAMO and have become more aligned with hardliners in his own party, as well as with previous Presidents, favoring military confrontation (Africa Confidential, 18 March 2016).

This report was originally featured in the October ACLED Africa Conflict Trends Report.