Political violence and protest events in Egypt have been rising since August 2016, largely driven by two dynamics. First, protests have rebounded nationwide coinciding with a seven-year high inflation rate of 15.5 percent in August (NYTimes, 20 October 2016). Second, violence against civilians reached its highest level since February 2016 as kidnappings surged in North Sinai; and off-duty police officers and military personnel continued to be targeted in wide-ranging militant attacks that spread from North Sinai to closer to the capital.

In recent months the shortage in supply of baby milk formula, wheat, and the most recently contested sugar has caused speculation that a major outbreak of social unrest is imminent (Daily News Egypt, 5 November 2016). Whilst protests have steadily risen from August – October, the deterioration in economic circumstances by itself is unlikely to spark mass, destabilising unrest (Ketchley, 2016). Instead, the protest landscape characterising Egypt is one of fragmentation where locally directed demands trump concerted efforts of national coordination. Throughout October, protests centred upon a myriad of localised interests including access to basic services in social housing units in 6 October City; demands to be rehired by factory workers at Tanta Linen Factory; rising apartment prices in Port Said; and cuts to electricity and water supply due to flooding in the Red Sea governorate.

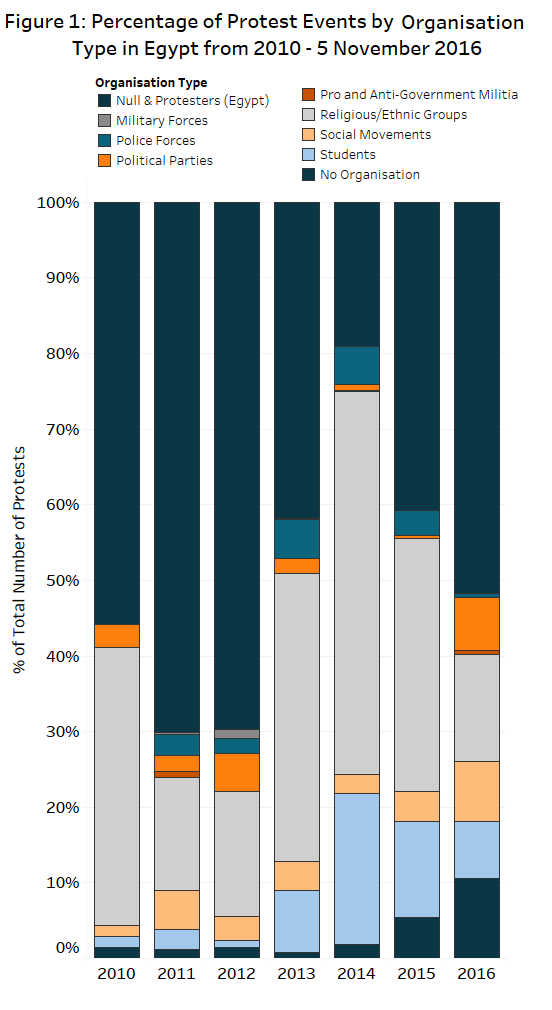

Calls for nationwide street protests on 11 November have gained attention in Egypt. These calls largely originated internationally by a Turkey-based activist and seemingly gained traction with the Muslim Brotherhood group ‘Anti-Coup Alliance’. In the run up to 11 November however, only very limited protests have been staged expressing direct support for, or momentum behind, the call to protest against economic conditions, with political parties withholding political backing (Albedaiah, 5 October 2016). On 21 October, the pro-Morsi Anti Coup Alliance staged a demonstration in the Menoufiya governorate after a housewife was arrested on charges of calling for protests on 11 November. Piggybacking on the arbitrary detention of civilians is unlikely to galvanise widespread support for the movement and obfuscates the economic grounds the protests are based upon. Speculation that the Muslim Brotherhood are the main instigators of these calls (Egypt Independent, 28 October 2016) demonstrates the improbability that any protests that emerge will spread and the threat it poses to the Sisi regime appears minimal, as religious/ethnic organisational leadership in protests in 2016 has dwindled from 50.6% of protests in 2014 to 14% of all protests in 2016 (see Figure 1).

Instead, the composition of movements and political & societal groups behind the protests suggest a growing role for organised labour unions where in October, six labour protests (both officially sanctioned and worker-led) were recorded compared to one in August and September respectively. In determining the impact these protests will have on trajectories of contention, during the Arab Spring “massive labour protests remained parochial, fragmented, and to a large degree sidelined from the unfolding political process” (Ketchley, 2016: 3). On this basis mobilisations by organised labour unions and professional groups is unlikely to translate into a cohesive opposition that has the potential to escalate. Furthermore, although police abuses have continued to beset Egyptian society and offered some signs of growing divisions between the security sector and the regime in October, el-Sisi has acted to contain the fallout. A prison break following riots in Ismailia resulted in Magdy Abdel Ghaffar sanctioning swift and sweeping changes in personnel in the Ismailia security apparatus as investigations were opened into the involvement of police in the jail break (MENAFN, 25 October 2016). El-Sisi continues to distance the police apparatus from continued violence against informal traders, describing them as isolated incidents by rogue police officers. Notwithstanding these signs of tension, the Egyptian military tightens its hold on Egyptian public life by wading further into the provision of goods and services to counter growing inflation in the wake of austerity measures set by the IMF (Al-Jazeera, 26 September 2016; Financial Times, 5 October 2016). Combined, these dynamics suggest that opportunities for revolt remain scant at this time.

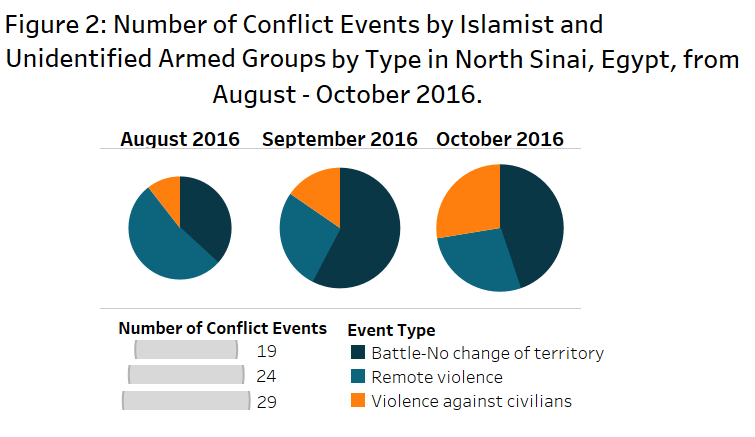

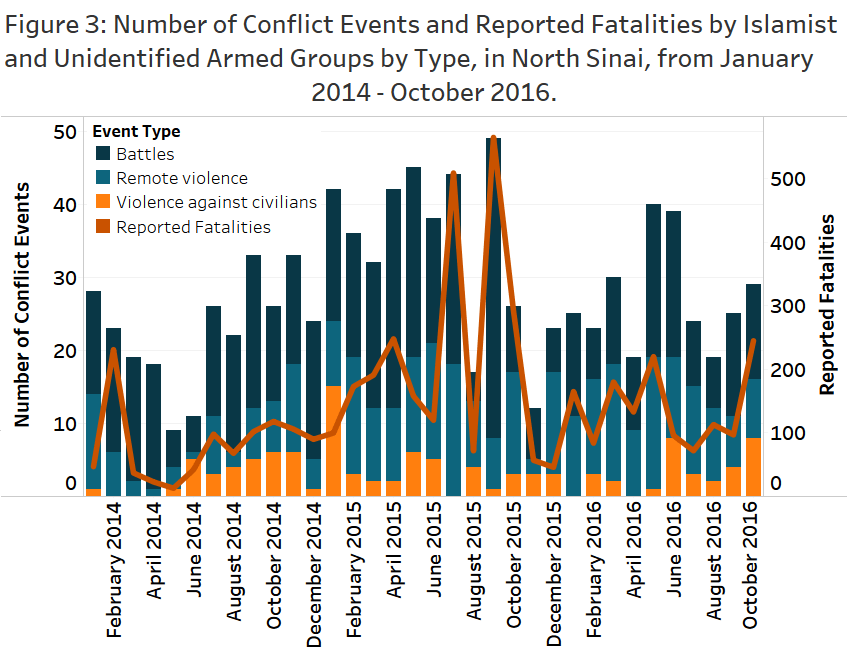

From August to October, violence against civilians became the tactic of choice by Islamist militants, Unidentified Armed Groups and the State of Sinai militant group in North Sinai, rising by 300% (see Figure 2). Overall counts of battles and remote IED attacks remained well below levels seen in May and June of this year. However, the nature of the violence in October shifted from usual patterns of police-targeted violence. Instead, militants more aggressively pursued kidnappings of civilians who were suspected of being army informants or vocal critics of Islamic State-linked attacks. This contrasts with other periods of higher civilian violence, such as June 2016, where non-commissioned police officers bore the brunt of militant advances (see Figure 3).

The early days of November however offer signs the a longer-term trend in which militants continue to primarily target high-ranking officials. In recent months, these attacks have usually occurred at their place of residence in Al-Arish and surrounding villages. The rate at which off-duty military officers are targeted may reflect the resumption in military raids and operations against Sinai militants following a large checkpoint attack on 14 October in the north-west near Bir al-Abd which left 12 soldiers killed.

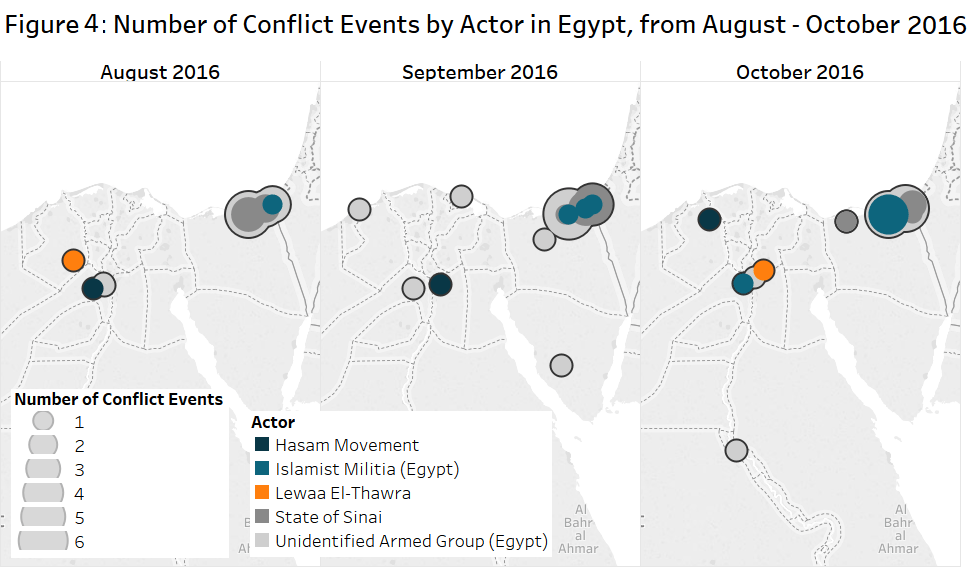

This most recent attack represents a geographical expansion in activity that until now has chiefly concentrated in the triangle between Al-Arish, Rafah and Sheikh Zuweyid and where the Egyptian military force directs its counter-terror activity (see Figure 4). Intermittent clashes have taken place in the central areas of the Sinai province in 2016 but the north-west of the peninsula has altogether avoided direct confrontations between military forces and the State of Sinai militant group. There have only been two recorded events in Bir al-Abd, both taking place in February 2016 and both involving a remote IED attack on police forces. Concern over this expansion may explain the highest recorded fatalities of 2016 as ‘Operation Martyrs Right’, a military operation against militant Islamist groups in North Sinai, responded to this provocation.

The complications the Egyptian army faces with eradicating the Sinai insurgency may come under further pressure in the coming weeks as new militant groups emerge closer to Cairo. Both the Hasam Movement and Lewaa El-Thawra have claimed attacks on security personnel in Al Qalyubiah, Al Menufiyah, Giza and a suburb of Cairo. Should these groups conduct further attacks, and with some arguing that the military’s role in civilian life is detracting from its security prerogatives (Al-Jazeera, 26 September 2016), El-Sisi will need to strategically supervise the armed forces to ensure their resources effectively address economic demands of protesters, security concerns in Upper Egypt, and counter-terrorist operations in the Sinai.