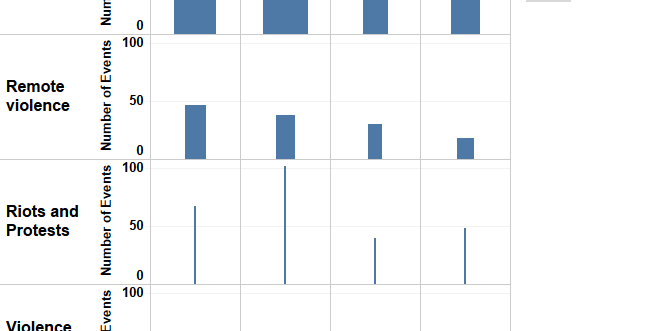

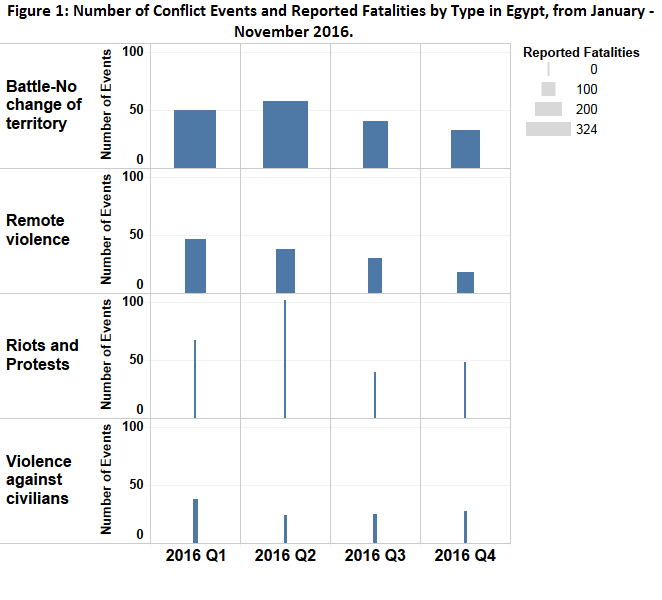

An overview of Egypt from January – December 2016 indicates a stable and consistent level of political violence and protest over the course of the year (see Figure 1). Overall conflict and political violence levels decreased, with battles witnessing the most significant drop of nearly 41% from 2015 to 2016. Whilst on the surface the conflict dynamics indicate a reduction in violence from the previous year, 2016 was characterised by multiple, and as of yet discrete, political contentions across Egypt. Notwithstanding the resistance trends reviewed below, the continued consolidation of political authority by the el-Sisi regime coupled with a reserved approach to non-violent resistance suggests that 2017 will see a continuation of low-level protest activity that remains undeveloped.

In 2016, the el-Sisi regime largely contained mass outbreaks of riots and protests across Egypt. Small-scale riots and protests simmered throughout 2016 as a diverse range of localised interests, grievances and movements cautiously took to the streets. Towards the latter half of 2016 economically-driven protests appeared to gain more traction as President Sisi’s promises of an economic turnaround continually failed to materialise and Egyptians were faced with rising electricity prices, high inflation, tax increases and staple food shortages (Reuters, 23 October 2016). However, the continued targeting and detention of journalists, lawyers and protest organisers has impaired any attempts to organise on a large-scale even against the backdrop of deteriorating economic conditions and living standards for many Egyptians.

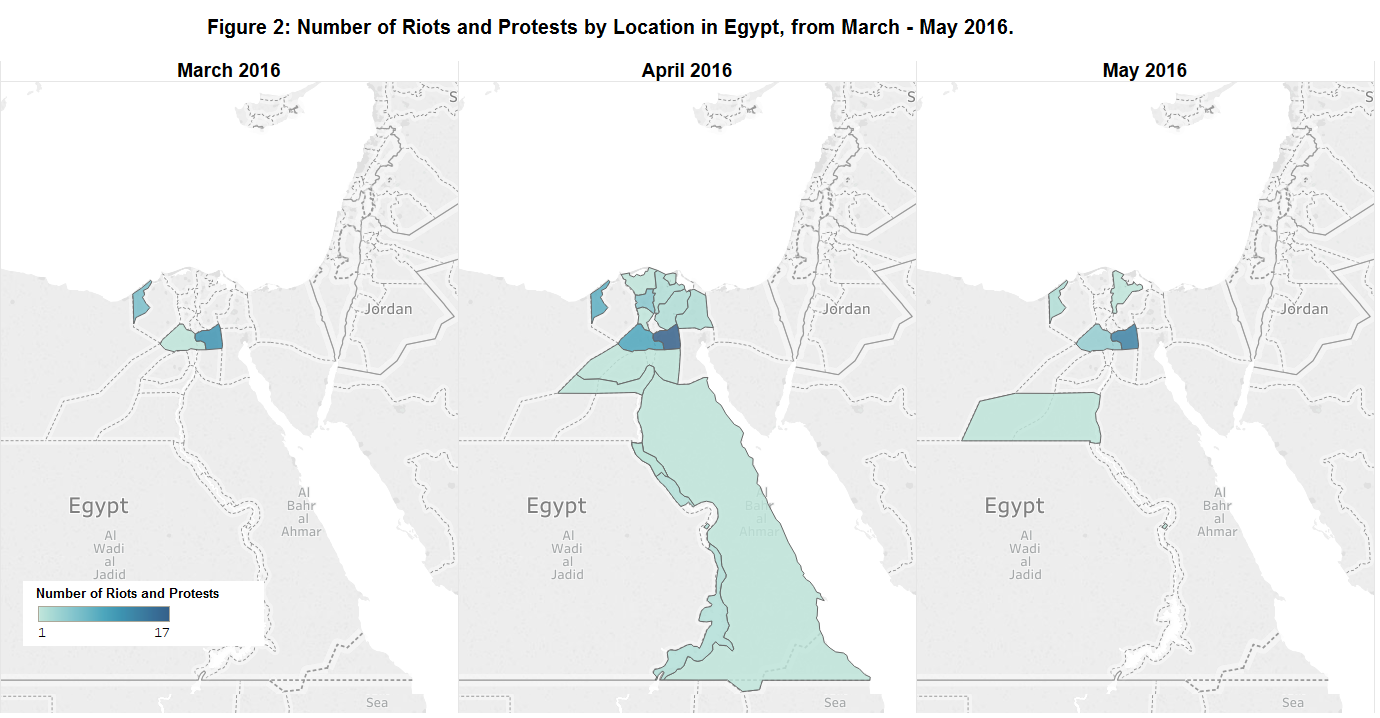

Two notable surges in protest activity occurred in April and again in November. In April, protests erupted against the transfer of two Red Sea islands, Tiran and Sanafir, to Saudi Arabia. This move by Sisi was widely criticised as unconstitutional, ceding control of the islands in exchange for political backing from Saudi Arabia and financial investment (BBC, 21 June 2016). The nationwide protests covered 18 governorates, predominantly concentrating in Cairo, Giza and Alexandria (see Figure 2). This contrasts with an average of 8 governorates per month experiencing protest activity. A court ruling in June eventually annulled the decision to transfer the islands and the events, in conjunction with geopolitical tensions, are widely cited as setting in motion a souring of Egypt-Saudi relations (Middle East Eye, 17 October 2016).

The second stirring of political disquiet emerged on 11 November as protesters objected to crippling price hikes. The group behind this call to protest remained obscure though the Muslim Brotherhood ‘Anti-Coup Alliance’ certainly had an organisational presence. Whilst these protests failed to produce any sustained momentum – largely owing to the fear of reprisal attacks for aligning with a group who the Egyptian regime would not hesitate to violently repress – demonstrations were recorded in 13 governorates indicating a substantially higher dispersion than the monthly average for 2016. Despite critical media coverage of the failings of the 11 November poverty protests, these two flashpoints demonstrate the residual capacity that Egypt retains to coordinate a non-violent campaign.

2016 saw a shift away from protests organised by religious groups – namely the Muslim Brotherhood – as organised labour and trade unions became a more prevalent force in the protest landscape (ACLED Conflict Trends Report November 2016). This coincided with the state’s attempt to consolidate the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (EFITU) under the government-sanctioned Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF), restricting its independence and space to freely operate and openly dissent. “If the protests organized by the youth, the Islamists, and the Egyptian civil society have been eliminated by the current state repression of oppositional movements, strikes and labor protests are still a matter of concern for the Egyptian authorities” (The Cairo Review, 22 September 2016). Whether the increased role of labour strikes and demonstrations is a response to the tightening state grip that threatens to stunt the development of an organised opposition or whether the state responded to a growing organisational capacity of non-government institutions is unclear but President el-Sisi’s refocusing demonstrates the potential for longstanding societal groups to reactivate and challenge the status quo.

Elsewhere in Egypt, violence against civilians predominantly perpetrated by police forces involved protesters, civilians, activists, and civil society members subjected to extrajudicial violence and claims of torture. Egypt’s security apparatus accounted for 45% of all reported violence against civilians; only the Islamic State affiliate group ‘State of Sinai’ were responsible for a larger share of civilian fatalities (38% compared to 30% by police forces). However, another important domestic trend prevalent during 2016 was the proliferation of sectarian clashes in Upper Egypt between Muslim and Coptic Christian residents. Rioting mobs have clashed over the controversial building of churches prompting commentators to ask whether Upper Egypt is becoming “the epicentre for sectarian violence?” (Al Arabiya, 29 July 2016). In a bid to defuse tensions, the Egyptian parliament issued a law that regulates the construction of churches thus upholding the rights of Coptic Christians. In reality, the law continues to discriminate against the minority population by imposing strict requirements on where churches can be built and many argue that it fails to tackle the systemic problem of perceived impunity for the perpetrators of religious violence (Human Rights Watch, 15 September 2016).

Looking forward to 2017, commentators are speculating over the prospects of a movement reminiscent of the 1977 bread riots (The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, 17 November 2016). Whilst the mechanisms through which the Egyptian economy is (mis)managed certainly provide the framing for large scale protests to return once again, observers should monitor the development of trade union and labour activity to gauge the likelihood of widespread, destabilising protests. Should workers and unions continue to engage in disruptive action they are likely to fall more clearly into the crosshairs of state repression. But their predisposition to remain as an autonomous movement with a narrow focus on immediate gains for workers such as salaries, working conditions and job security will likely impede large scale nonviolent coordination. As such, Egypt’s protest landscape is likely to be characterised by pockets of spontaneous rioting over deteriorating economic conditions (The Economist, 12 November 2016).