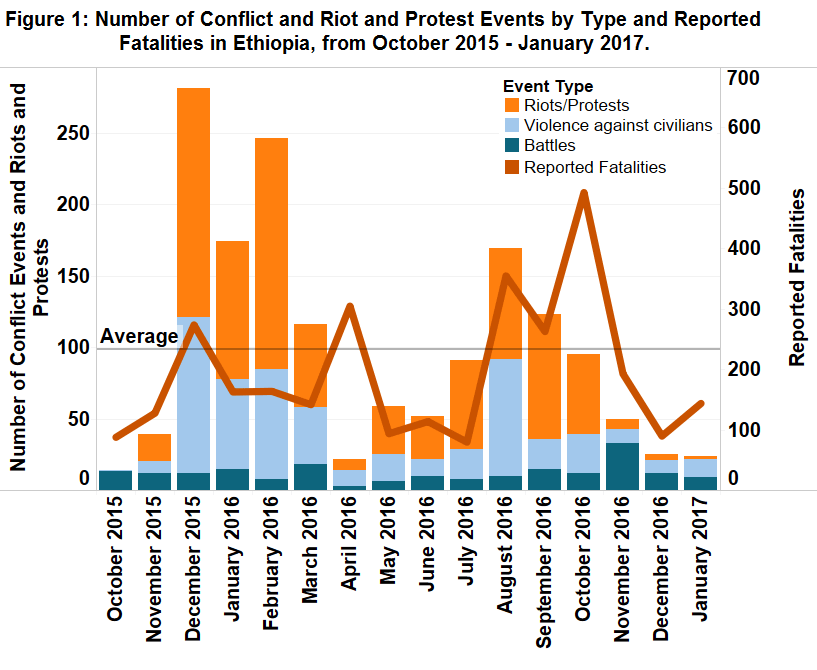

The nearly 3,000 fatalities reported between November 2015 and January 2017 rocked Ethiopia and the international community. Unprecedented waves of popular mobilisation in the country mainly drove these trends. Since November 2016 however, the number of riots and protests significantly reduced, giving way to a political violence landscape now dominated by battles and violence against civilians (see Figure 1). Conflict levels came close to those of 2002, when heavy clashes occurred between government forces and a number of rebel movements across the country, particularly the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the Ogaden National Liberation Army (ONLA).

Protests since November 2015

Mass protests first swept across the Oromia region in November 2015, reflecting widespread discontent with a large-scale development plan promoted by the Ethiopian government, which, Oromos feared, would marginalize and deprive farmers from their ancestral lands. Although the plan was suspended in January 2016, mobilisation continued and spread across the region, revealing widespread mistrust and discontent over authoritarian rule, the wrongful use of lethal force by security forces, and corruption among local and national elites (ACLED, May 2016). Although protests remained largely peaceful, the increasing lethality and indiscriminate nature of state repression to control the protests contributed to escalate and diffuse the tensions, with more incidents of riots since mid-2016, and protests erupting in Amhara and in the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s region (Africa Confidential, 22 July 2016; ACLED, November 2016). The government’s violent crackdown on protests is believed to have killed more than a thousand people over one year and led to the arrest and detention of thousands of people, including prominent opposition leaders and journalists.

Violence flared up after heavy casualties at a religious festival in Oromia on October 2nd, which the opposition blamed on government forces. In its response to the violence, the government proved unable to mitigate its repressive measures by declaring a six-months country-wide state of emergency for the first time in 25 years (ACLED, November 2016; BBC, 17 October 2016; HRW, 31 October 2016). Within two months, at least 24,000 people were arrested and detained for their alleged participation in anti-government protests, and sent to camps for “training” (African Arguments, 26 January 2017; HRW, 22 December 2016). This includes one of the highest-profile Oromo activists, Merera Gudina, arrested on 30 November for denouncing the government crackdown on protests at a European Parliament hearing in Brussels (Africa News, 27 January 2017). This also includes Oromo and Amhara police officers arrested and detained by Tigray federal forces, highlighting their control over politics and security in the country (ESAT News, 1 December 2016). Cases of killings, torture and abuse in prisons across the country were reported on several occasions, such as the alleged killing of 85 prisoners at Tolay military camp in Jimma after protesting harsh punishments early November (ESAT News, 5 December 2016; OMN, November 2016).

Since November, protests and riots largely dissipated across Ethiopia, most likely as a result of the restrictions imposed by the state of emergency and the accompanying repression. From 56 in October, reported riot and protest events dropped to 7, 4 and 2 between November and January 2017 respectively (see Figure 1). The government’s limited response to calls for deep structural reforms by protesters seems unlikely to have satisfied the opposition. For instance, despite a departure from tradition through the appointment of technocrats to senior positions as opposed to political loyalists alone, changes introduced in the Prime Minister’s Cabinet seem to suggest only minimal ideological repositioning, not least because no changes were brought to security forces’ Tigray-dominated leadership (Africa Confidential, 2 December 2016). Analysts are also pessimistic about the ability of the opposition to make any gains in the next local and national elections, despite the government’s willingness to renew the electoral system. Further, the likelihood that any major player will be affected by a ramping up of corruption prosecutions in the next few months (Africa Confidential, 20 January 2017) is negligible. This could lead to a re-energisation of protests once the state of emergency is lifted in April, or urge some protesters to assert their demands through different means.

New trends since November 2016

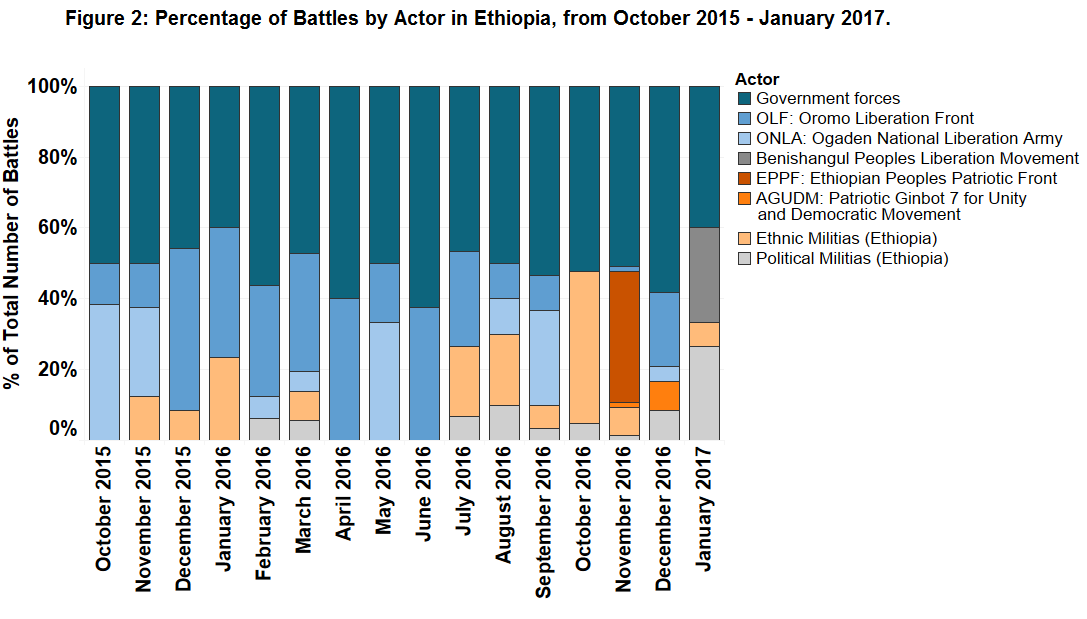

Overall levels of conflict, rioting and protesting reduced by half between October and November, and by another half between November and December, reaching pre-Oromo protest levels. The significant reduction in riots and protests was counter-weighed by sustained levels of battles engaging government forces with regularly operating rebel groups like the OLF and ONLA, and other political and ethnic militias (see Figure 2). This might point to an escalation of the protest movements from a largely peaceful unrest to an armed struggle taken up by local armed militias and rebel movements united in their aim to remove the current regime.

Ethnic and political militias have been particularly active since November with a number of attacks targeting government officials and structures. Indigenous people and farmer militias clashed with security forces on several occasions in Oromia (OMN, November 2016; ESAT, 10 November 2016). In Amhara, several armed militias also announced their reorganization to fight oppression of all Ethiopians by the regime in collaboration with groups with similar aims (ESAT, 30 November 2016; ESAT, 23 November 2016). A few weeks later in January, seven bomb attacks by unknown groups in the space of two weeks targeted hotels where officials were meeting or businesses that they support in Amhara’s Gonder (ESAT News, 4 January 2017).

Unprecedented joint battles between security forces and foreign-based groups – namely the Ethiopian People’s Patriotic Front (EPPF) and the Patriotic Ginbot 7 for Unity and Democratic Movement (AGUDM) – were also reported in November in Amhara and Tigray, resulting in heavy casualties and territorial gains (Zehabesha, 23 November 2016). AGUDM fought government forces independently in Amhara, Oromia and Tigray regions later in the month, leading to further casualties (ESAT, 24 November 2016), and announced that it was now operating from northern Ethiopia and training dozens of defectors who joined their movement, including government soldiers and Church leaders who had previously participated in the organization of protests in Amhara (ESAT, 8 December 2016),

Clashes also resumed in the Benshangul-Gumaz region between the government and the Benishangul Peoples Liberation Movement since end December (ESAT, 6 January 2017), while the Afar Revolutionary Front condemned the state of emergency as a way to legalise the government’s militarised response to the uprisings, and vowed to continue resistance (ESAT, 22 December 2016).

As a result of these clashes, the government detained a number of people accused of supporting rebel militias fighting them and allegedly looted and burned down their properties and crops (ESAT, 27 December 2016; ESAT, 9 December 2016). Rising cross-border attacks have also been carried out by the Somali region special police forces into Oromia since December, resulting in the reported killing of at least 47 people (OMN, 14 January 2017), and further pointing to the heavy repercussions of insurgencies for civilians.