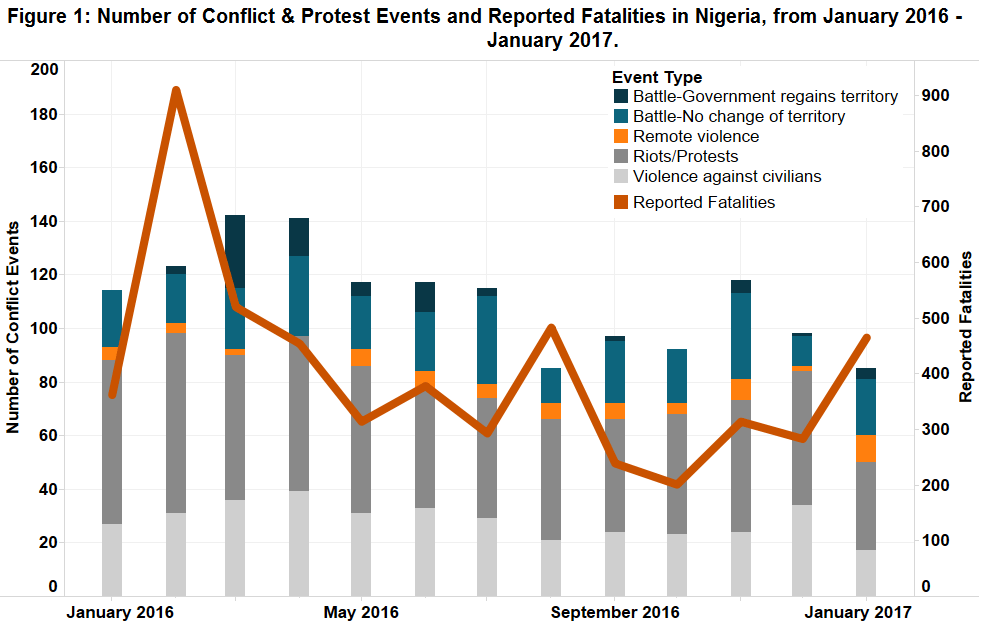

Over the course of 2016, Nigeria witnessed a general downward trend in violence starting in March 2016. However, a significant spike of over 900 fatalities recorded in February preceded this downward trend, which was almost 550 more than the month before (see Figure 1). Out of the total fatalities recorded in February, 358 were reported during clashes between state forces and Boko Haram, another 60 were the result of a Boko Haram suicide bombing that targeted an IDP camp in Borno, while 300 were caused by Fulani militias which staged a day-long coordinated assault on several Agatu communities. Together these three dynamics can be see as a microcosm of the conflict landscape in Nigeria over 2016 while their diminishing but significant impact over the year can offer important insights looking ahead to 2017.

The battle against Boko Haram in 2016 turned decisively in the state’s favour during the period from February to April 2016 (see Figure 1). State forces killed or captured a large number of Boko Haram fighters in February, which paved the way for them to secure significant amounts of territory from the insurgent group in March and April (see Figure 1). This trend would continue throughout the year, albeit at lower levels, and culminate in the important strategic and symbolic victory of clearing Boko Haram out of the Sambisa Forest, their primary stronghold, in mid-December 2016 (Vanguard, 26 December 2016). During this operation, the military reported that over 1,880 civilians had been rescued and hundreds of Boko Haram insurgents captured, dealing a serious blow to the group (Newsweek, 22 December 2016). These military successes translated into a clear reduction in recorded conflict-related fatalities in Nigeria, which in the last few months of 2016 were at their lowest levels since February 2013. This prompted Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari to declare victory against the group (Signal, 24 December 2016). However, despite the considerable territorial losses Boko Haram has suffered in 2016 (see Figure 1), the group is believed to still possess bases within Nigeria’s neighbours’ territories across the Lake Chad basin (Al Jazeera, 27 December 2016).

But despite losing its major strongholds in Nigeria, Boko Haram continues to possess the capability to successfully attack soft targets in the country, with the most recent example being a suicide bombing of Maiduguri University on 16 January 2017 which killed at least 4 people, including two bombers (Al Jazeera, 16 January 2017). Across 2016, ACLED recorded 51 events of violence against civilians by Boko Haram which resulted in at least 550 fatalities. This represents an average of 10.8 fatalities per event. In comparison, Al-Shabaab’s civilian fatality count over the same period was 378, with an average of only 1.9 fatalities per event. This comparison is particularly notable as ACLED recorded a total of 275 violent events involving Boko Haram in Nigeria, which was only about a quarter of the 1,089 violent events involving Al-Shabaab in Somalia, a group which continues to control a relatively large amount of territory compared to Boko Haram. Based on this data, it is likely that as Boko Haram continues to lose ground on the military front, the number of attacks against civilians by the group will likely remain high going into 2017. However, the existence of Boko Haram’s Barnawi faction, which has explicitly stated it is moving away from attacks that target Muslim civilians (Mail & Guardian – Africa, 28 September 2016), may moderate this trend.

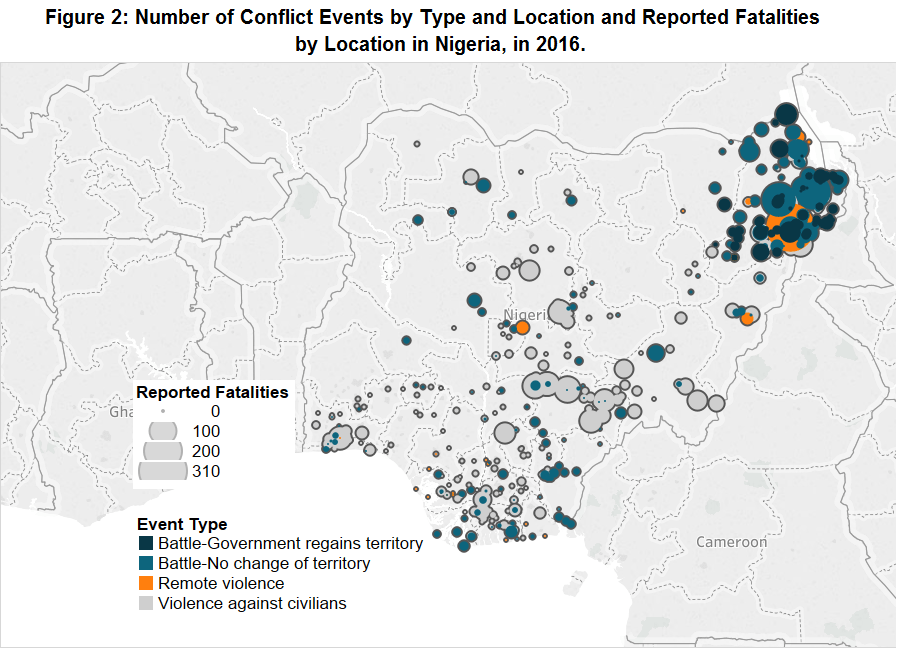

Other dynamics represented by February’s spike in violence is the ongoing conflict between largely Fulani herders and non-Fulani farmers in central Nigeria (see Figure 2). The primary group driving this violence are Fulani ethnic militias, which were involved in twice as many events in 2016 as all other ethnic militia groups recorded by ACLED in Nigeria combined and were responsible for four times as many fatalities. Although events involving Fulani ethnic militias included several battles, the vast majority of these events were violence against civilians which resulted in 884 fatalities, representing an average of 11.8 fatalities per event, even higher than Boko Haram over the same time period. Many of these attacks, which were most prevalent during 2016 in the states of Benue, Kaduna, and Taraba (see Figure 2), have also resulted in large displacements of people and often involved the burning down of homes and villages (BBC News, 5 May 2016), which could amount to ethnic cleansing. The disputes behind the violence allegedly focus on the use of resources such as farmlands, grazing areas, and water, with both sides claiming grievances against the other. Looking forward, a report by the Famine Early War System Network (FEWS-NET) predicts a credible risk of severe food insecurity in Nigeria (Premium Times, 26 January 2017). Within this context, serious outside intervention will likely be necessary to avoid rising violence between herders and farmers and a humanitarian crisis in central Nigeria over the course of 2017.

Although violence overall decreased in Nigeria in 2016, each of these dynamics remain volatile, with the possibility of inter-play between them offering an extra dimension of concern going forward. The potential for significant resource competition and displacement due to drought and famine could lead to greater instability across Nigeria’s central and northern areas, which could in turn put greater pressure on Nigerian security services and offer new opportunities for Boko Haram to press over-extended state forces (Reuters, 13 January 2017), while also providing new recruitment opportunities among disaffected populations (Mercy Corps, February 2016). Dynamics not focused on here, such as the renewal of conflict in the Niger Delta (The Economist, 17 June 2016), could also put pressure on the state both militarily and financially as infrastructure continues to be targeted in that region. While the overall trend of decreasing violence in Nigeria is evident, this outcome will remain fragile if further action is not taken by the government to bolster resilience and deal with the underlying issues behind Nigeria’s conflicts.