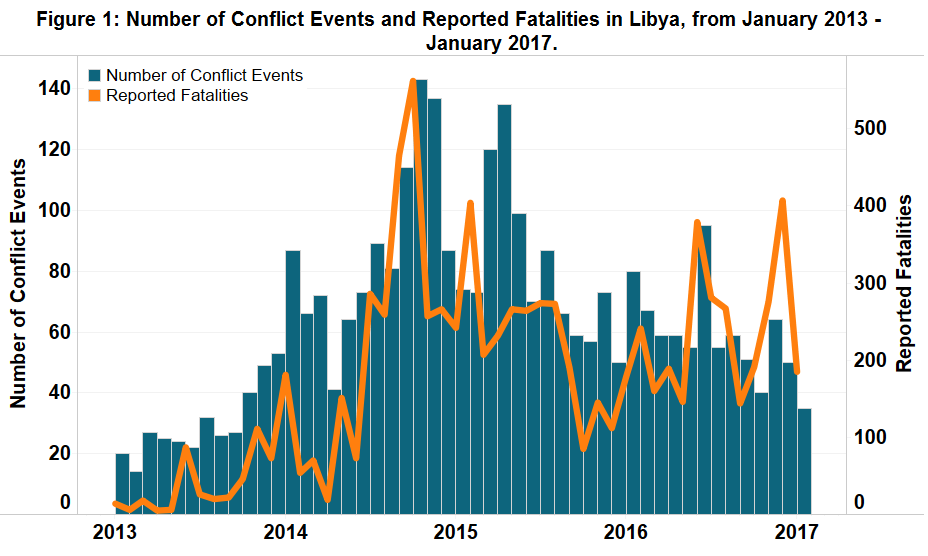

Conflict and political violence events in January 2017 dropped to their lowest recorded levels since September 2013 (see Figure 1). Conflict-related fatalities were subject to an artificial spike in December 2016 after UN-backed Government of National Accord forces in Sirte reported the discovery of over 250 militant bodies during clean-up operations following the announcement that they had liberated the town from Islamic State control (The New Arab, 5 December 2016).

This apparently low event count hides political manoeuvring below the surface which is likely to shape the nature and intensity of military engagements in Libya in the next few months. These are: 1) the relatively synchronous military successes in Sirte and Benghazi’s Ganfouda district; 2) military action between armed forces under Khalifa Haftar and the Misratan Third Force and Brigades for the Defence of Benghazi in the southern Libyan region of Fezzan that risk turning into a war of attrition; and 3) a temporary lull in inter-brigade fighting in the capital, Tripoli.

Each of these developments indicates a significant risk of escalation each with the potential to shift the rules of the political game in Libya, promoting the political weight of one faction over the other. However, given current dynamics, low-level tit-for-tat attacks are likely to characterise the conflict landscape.

Military Success in Sirte & Benghazi

The Government of National Accord (GNA) appeared to have its legitimacy boosted in early December 2016 as Operation Bunyan Marsous (Solid Structure) forces, aligned with the Tripoli-based government, succeeded in wresting back control of Sirte from Islamic State control. At least rhetorically, officials have been careful not to underplay the continued threat posed by Islamic State militants who may have relocated to other areas including Sabratha (BBC News, 19 February 2016). Nevertheless, serious questions have been posed about the militant groups organisational capacity after the military victory, as well as uncertainty that has been cast over predictions that the destabilising influence of the group will spread like contagion to sub-Saharan Africa (Global Trends Annexes, 2017).

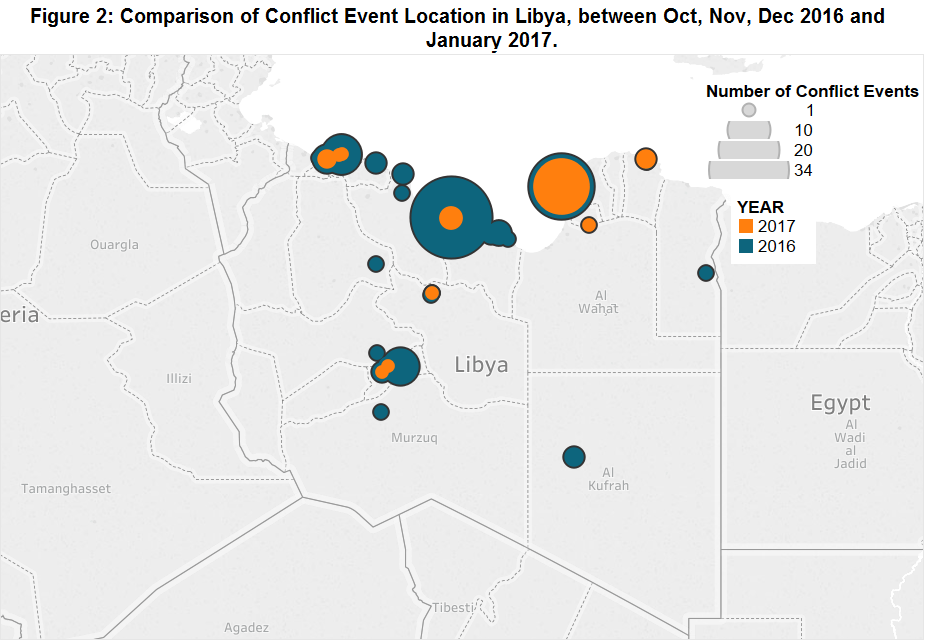

However, this much-needed boost to Fayez al-Sarraj and the UN-backed government was short lived as on 25 January 2017 the Libya National Army (LNA) forces in the Ganfouda district of Benghazi – one of the last enclaves of Ansar al-Sharia and militants under the Benghazi Revolutionaries Shura Council (BRSC) – announced significant advances into and full control of the area. Later reports suggest that some areas of Ganfouda district, particularly around the Busnaib area, remain volatile with militant activity (see Figure 2). Having cultivated outside support from Egypt’s el-Sisi, Russia, and the U.S. during the offensive in Benghazi, Gen. Khalifa Haftar and the House of Representatives government appear to be the strongest political players in the on-going negotiations (VOA, 13 January 2017). This position has only further entrenched by the success in Ganfouda in January.

GNA vs. LNA

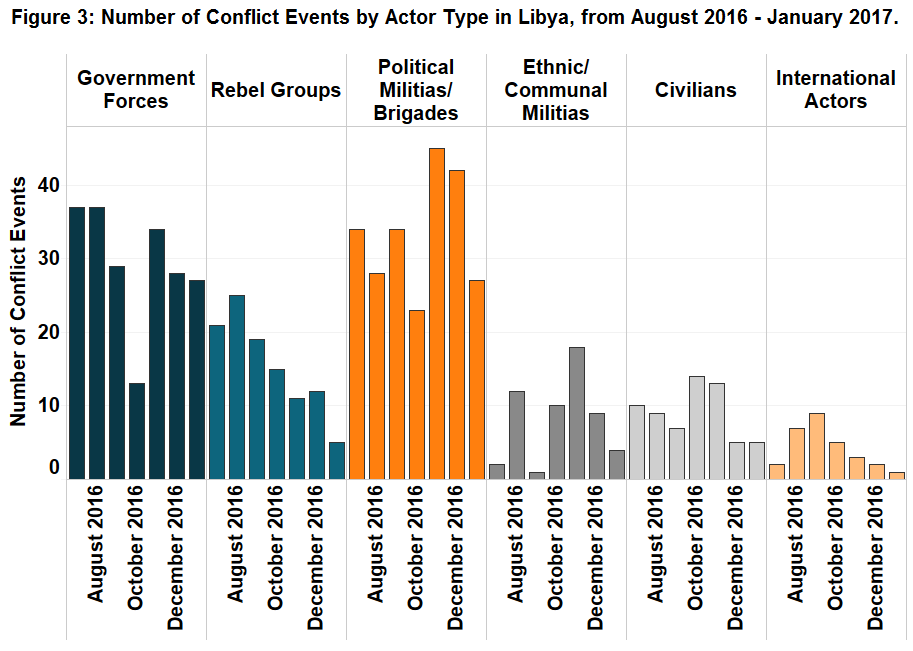

As the two most prominent battlefronts are overcome and the Islamic State and BRSC no longer dominate the attention of the competing military and parliamentary groups (see Figure 3), their focus is beginning to turn towards each other. At least in the short-term, the geography of conflict is concentrating in the southern Fezzan region. Secondary to the rebel violence in Sirte and Benghazi, the eruption of violence in the south and central region of Libya has been characterised by militia brigades clashing with Haftar’s LNA. In December 2016, the Brigades for the Defence of Benghazi (BDB) – nominally aligned with al-Qaeda-affiliated Ansar al-Sharia and BRSC militants in Benghazi (TRAC, 2017; Long War Journal, 22 July 2016) – launched attacks on three towns in the Sirte oil crescent including Bin Jawad, Nawfaliyah and al-Sidra in an apparent move to disrupt or control the oil terminal region. The LNA beat off these attacks and launched airstrikes against the group in late December further south in al-Jufrah.

Some analysts establish that the BDB lacks strength to confront Haftar’s LNA itself and is leveraging the power of other powerful brigades to ‘carry out its bidding’. From this stance, it is seen to be dragging Misrata into the fight; the urgency with which it will want to do this now has heightened given the recapturing and clearance of Ganfouda of BRSC militants by the LNA, tipping the power balance in Haftar’s favour (War is Boring, 11 January 2017). This geographical relocation in confrontations represents a resumption of the dominant cleavage between the competing power bases in the east and west of Libya and provides new opportunities for temporary alliances to form. This in turn creates the potential for new conflict agents and identities to emerge and activate, especially as long-standing, localised ethnic grievances are played off of one another.

Nascent attacks also emerged more prominently between the LNA and the Misratan Third Force around the southern region of Sebha for control of the Tamanhint airbase. This flashpoint appears to be a strategic move by Haftar to divide the operational capacity of Misrata. The Third Force are stationed in the southern city of Sebha and have been since 2014 after the Libya Dawn coalition sent them to secure and provide stability (Libya Security Monitor, 5 November 2015). Intermittent clashes between the Third Force and the LNA have occurred since, notably in March and April 2015 with the aim of gaining control of the Brak al-Shati and Tamanhint airbases where the Misratan forces were based. Haftar appears to be using the BDB and Misratan Third Force as strawmen in order to discredit any potential opposition to him consolidating power. The Third Force has come under heavy criticism recently in two areas it has had an operational presence. After Sirte was liberated by the Bunyan Marsous operation comprising mainly of Misratan forces – local elders accused these soldiers of deliberately stealing power, creating blockades, looting, and seizing property (Libya Herald, 26 January 2017). Furthermore, the Brak al-Shati mayor accused the Third Force of blocking aid delivery to the south (Libya Herald, 24 January 2017), though this was vigorously denied by the Misratans.

Whether or not this has been orchestrated by Haftar to stir animosity and to discredit Misrata’s governance abilities or security provision remains unknown. What is certain though is that before this move, the Third Force answered to the Misratan Military Council and remained outside the Bunyan Marsous structure, unlike other Misratan brigades. Since renewed clashes between the Third Force and the LNA, Ahmed Maetig, the Deputy Prime Minister in the Presidency Council and a prominent Misratan, has announced a concerted effort to create a unified ‘western’ Libyan army that will unite the various militias currently operating in accordance with the GNA (Libya Herald, 30 January 2017). The Misratan Military Council back this move, despite being traditionally more hardline in their approach to Libyan politics and will incorporate the Third Force. This may be a pre-emptive move to prevent further complex, temporary coalition building between the many prolific brigades operating inside Libya that threaten to divide Misrata. The Third Force has already built alliances with ethnic militias in and around Sebha that has acted to renew and stoke further clashes between the Awlad Sulaiman and Qaddadfa tribes. Whether or not this was the intention, it indicates that significant developments in fighting are likely to revolve around direct confrontations between LNA and consolidated GNA forces around road networks, rather than the disparate and semi-autonomous militias that have dominated up until this point.

Insecurity in Tripoli

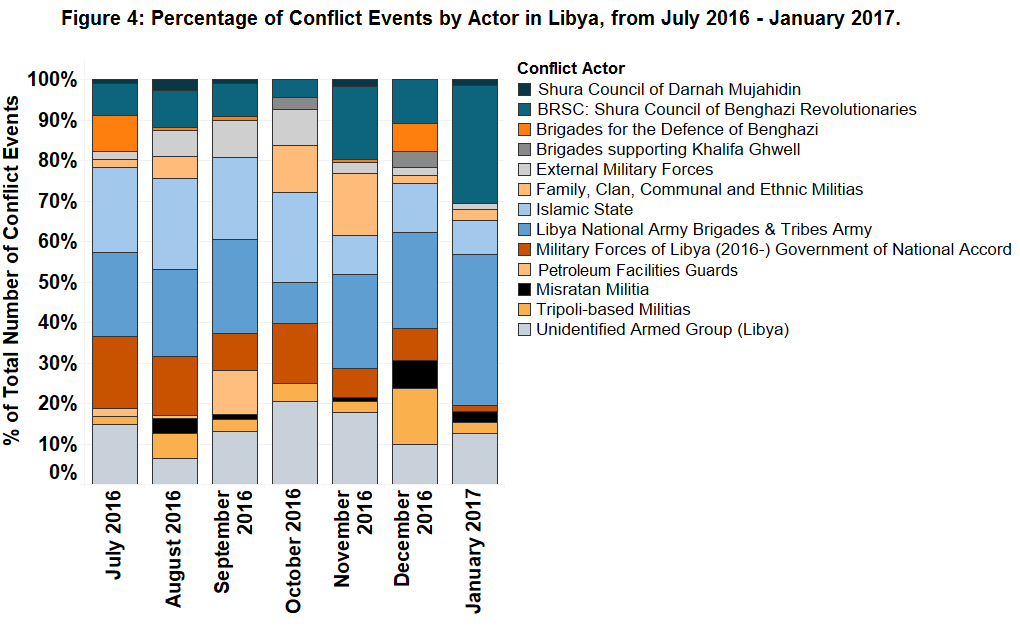

Frustration has grown over the lack of security in Tripoli as free-roaming, unaccountable militia activity has disrupted electricity power and kidnappings continue to undermine the safety of residents. ACLED reported the most substantial Tripoli-based militia competition in December 2016 where militia attacks accounted for 13.9% of conflict activity with events falling to 2.8% of activity in January 2017 (see Figure 4). In the greater Tripoli region as well as to the west in Zawiya, the distinction between political and criminal violence has proven difficult to untangle as instability created through oil and fuel pipeline shutdowns has been characterised by quasi-criminal groups and smugglers with close ties to prominent families within Zawiya. It is unclear as to whether this is localised posturing to secure control over lucrative smuggling networks and livelihoods or whether it feeds into the wider, national-level conflict.

Two trajectories present themselves for conflict in Tripoli. First, inter-militia fighting may decrease following the military success of the LNA in Benghazi. As the threat of an LNA offensive on the capital grows, a shift in coalition-building dynamics may occur where the consolidation of pro-government militias takes predominance over competition between them. If Haftar’s stance towards the GNA grows more aggressive, militias will need to act as a bulwark against an LNA attack or exit the political-military landscape. Second, in the short-term, as the south becomes the most recent geographically situated expression of a continuing dynamic in which neither the LNA or GNA-affiliated militias and military units make substantial progress, militias in Tripoli may continue to compete for influence and involvement in the transitional environment (Global Observatory, 29 June 2016).

Khalifa al-Ghwell’s attempted coup in Tripoli in October 2016, described as a ‘miniature coup’ (VOA, 13 January 2017) was followed by a further ‘coup’ in early December marked by street clashes and limited takeover of ministry buildings. This lukewarm flare-up of violence signals the lack of support for a full-scale coup and demonstrates the current logic of violence that paralyses the whole of Libya. Political developments across the country mirror military developments as localised pockets of fighting and resistance continue with stalemates playing out. A lack of military hardware, soldiers stretched across multiple battlefronts and insufficient capacity to dominate or monopolise create recurrent and oscillating shifts in the target of violence with one side failing to capitalise on an advantage and consolidate a strengthened position. Until one side seizes advantage – currently Haftar is the most likely contender – armed confrontations where attrition is the mechanism will continue like business as usual.