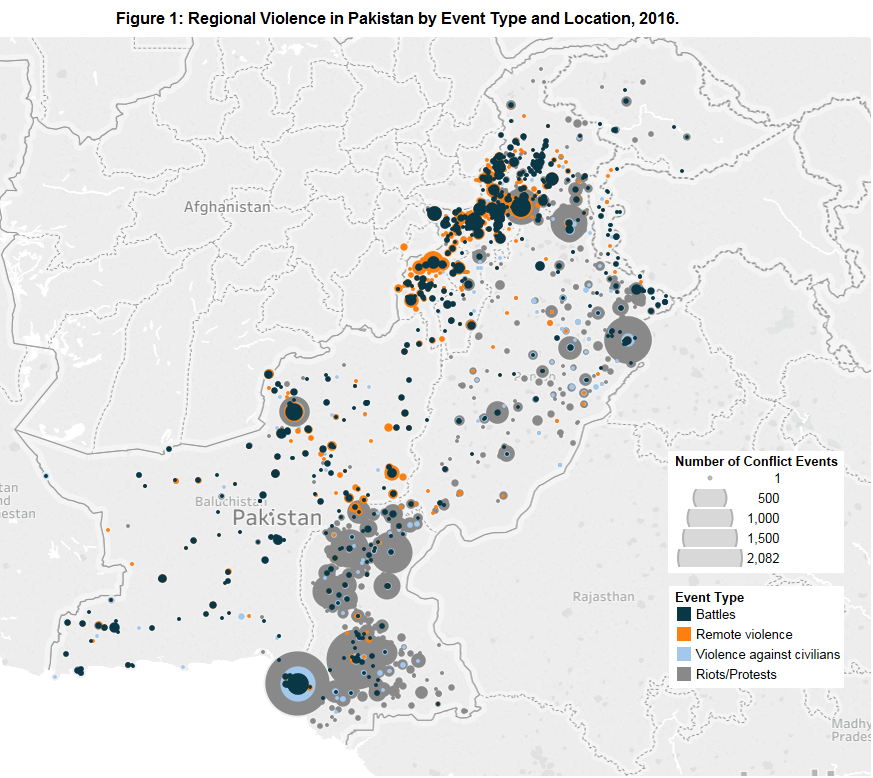

Pakistan’s five provinces contain very different conflict environments (see Figure 1). This piece reviews data collected on armed, organized violence, riots and protests from 2010-2016. It demonstrates the multifaceted nature of conflict across the country, and the difficulty in establishing peace across the state. Pakistan’s most populous provinces, Punjab and Sindh, generally see less armed, organized violence but a large number of riots and protests. Yet the large cities, especially Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad-Rawalpindi, are periodically targeted by groups such as the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Al Qaeda, or their affiliates in mass-casualty attacks.

In contrast, Balochistan, which hosts a long running separatist conflict, and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), the main recruitment base and operational area of the TTP, both possess highly disproportionate rates of violence per capita compared to Sindh and Punjab. Balochistan sees a relatively large number of battles, incidents of remote violence (bombing), and violence against civilians, but also riots and protests over various issues. FATA experiences the highest rate of battles, bombings, and violence against civilians, with drone strikes predominantly clustered in North and South Waziristan. Its is often the site of periodic offensives by Pakistan’s military to disrupt militant networks (Daily Mail, 29 January 2015).

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) is a frontier between the more violent areas of Pakistan and the more stable and secure provinces of Punjab and Sindh. KPK sees considerable violence in Peshawar, its capital, which lies close to the border with FATA. The city is the site of many attacks on police and military personnel, as well as bombings of markets and shops. Outside Peshwar, the Malakand/Swat area has been the most eventful area of KPK over 2010-2016, despite the various military offensives prior to 2010 which diminished the operational capacity of groups like the TTP in the region (Al Bawaba, 4 June 2016).

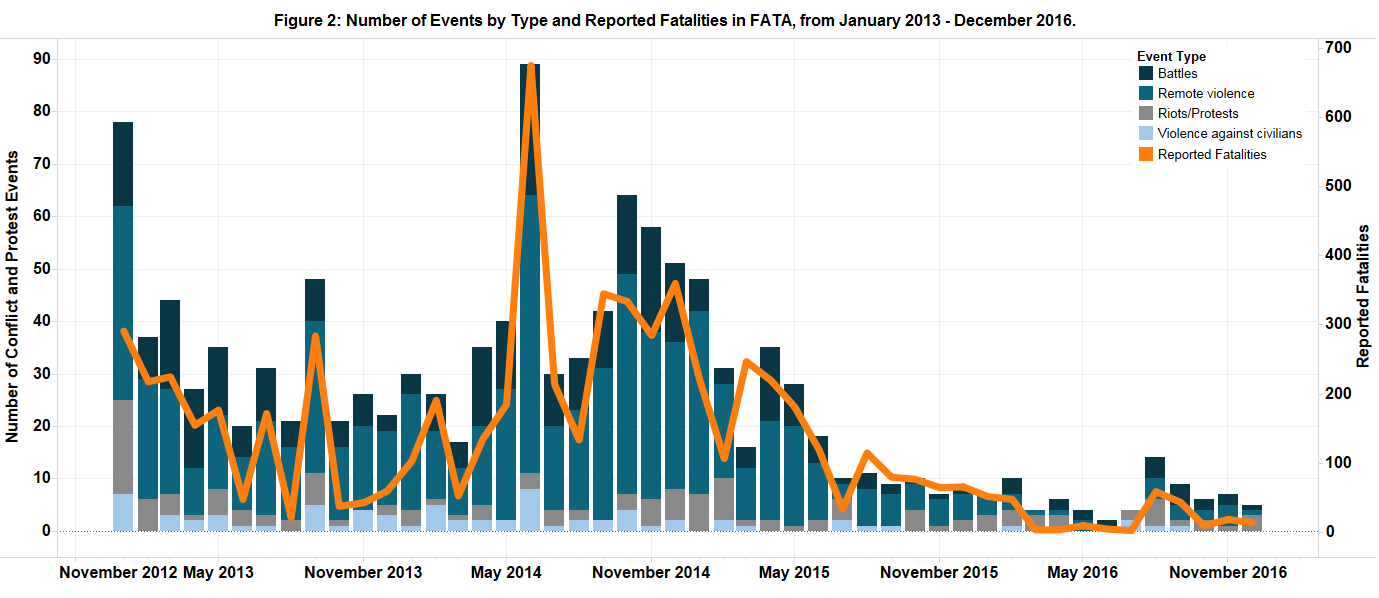

In FATA, a relatively steady level of violence throughout 2013 and the first half of 2014 concluded with a dramatic spike in both events and fatalities in June 2014 (see Figure 2), which marked the beginning of Operation Zarb-e-Azb (Sharp Strike) (Economic Times – India, 15 June 2016), a military offensive commenced after the June 8, 2014 attack on Jinnah International Airport (Reuters, 12 June 2014). This highly-publicized attack by a group of TTP and Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) militants left at least 21 people dead (see Figure 2). Violence decreased in the following months overall in FATA, but resumed with another highly-publicized attack on December 16, 2014 on an Army Public School in Peshawar (CNN, 17 December 2014) where militants killed 132 schoolchildren and 9 teachers (see Figure 2). This attack is infamous for being one of the deadliest in Pakistan’s history, and the most brutal in terms of psychological impact.

Following the Army Public School attack, the government announced the creation of the National Action Plan (Link) in January 2015; this was a government-wide supplement to the military approach of Operation Zarb-e-Azb. The plan allowed for the deployment of a federal armed force–the Pakistan Rangers – in Karachi and other large cities, the creation of a new anti-terrorism force, enhanced power for the Foreign, Finance, and other ministries to crack down on terrorist financing, and the expelling of Afghan refugees. By March 2016, violence in FATA had reached the lowest point since the beginning of 2010 (see Figure 2), and it is at this point that Operation Zarb-e-Azb shifted into its “clearance phase” after the army reported that 90% of North Waziristan had been cleared (Dunya News, 16 November 2014).

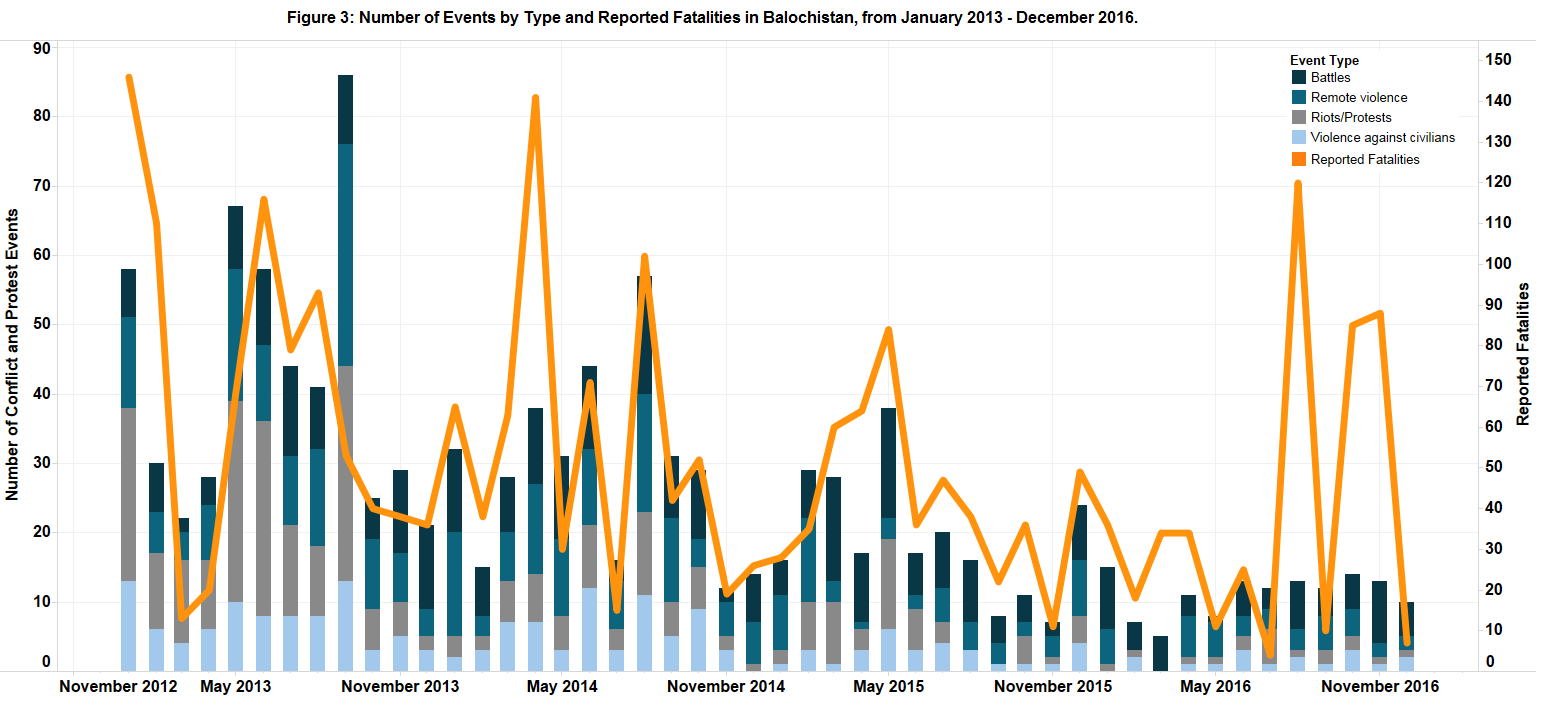

Together Operation Zarb-e-Azb and the National Action Plan are the main drivers of the significant decrease in both fatalities and events in FATA over the course of 2015 and 2016 (see Figure 2). This trend of decreasing violence was also mirrored to some extent in Pakistan’s most populous regions, Punjab and Sindh, although periodic mass-casualty attacks in both provinces over 2015 and 2016, are reminders that soft targets remain vulnerable despite the success of offensives in the Tribal Areas. This to some extent has also been recorded in Balochistan (see Figure 3), although other dynamics are also at play in that region which suggest more is going on under the surface.

Balochistan has generally seen fluctuating violence over the years. Following the beginning of Operation Zarb-e-Azb and the implementation of the National Action Plan, a broad downward trend in violence is evident (see Figure 3).But similar to Sindh and Punjab, Balochistan has witnessed increases in mass-casualty attacks, with three in the second half of 2016. The most significant was the August 2016 Quetta Government Hospital bombing which killed 93 people (India Today, 8 August 2016), making it one of the deadliest attacks in Balochistan’s history and the deadliest recorded attack in the region. There are two main factors which explain the recent rise in frequency of mass-casualty attacks, and suggest that violence is likely to begin to rise overall in Balochistan.

The first factor is directly related to Operation Zarb-e-Azb: the diminishing violence in FATA is correlated with secondary effects of increased mass-casualty attacks in large cities outside the region, including Karachi, Lahore and Quetta, respectively the most populous cities in Sindh, Punjab and Balochistan (see Figure 3). This suggests that militants have been pushed out of the tribal regions into the cities, retaining their capabilities to carry out large-scale attacks on soft targets (Awaz.TV, 10 August 2015). Although the Operation disrupted networks, which is reflected by the diminished number of events and fatalities overall since 2014, the spike in fatalities since August 2016 suggests that militants are overcoming this disruption (see Figure 3). Further, new actors may be gaining ground as the three major attacks in the second half of 2016 were either claimed by groups affiliated with ISIS or by ISIS itself.

The second factor is the beginning of activity along the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which links the deep sea port at Gwadar to China’s Xinjiang region (Al Jazeera, 12 November 2016). Although CPEC was announced in 2013, only in November 2016 did the first convoy of exports arrive at Gwadar. As it has come online, the CPEC disrupted the region’s traditional power relationships by introducing the possibility of new development and considerable prosperity to the region (The Diplomat, 16 November 2016). This will likely lead to a diminishing of Balochistan’s status as a frontier region and an increase in stability as economic incentives motivate the need for greater security in the region. However, desires by local actors to shift the balance of power in their favour coupled with the increased presence of militants from FATA are likely to mean considerable instability over the short-term.

While FATA and Balochistan will clearly be important regions to watch in the coming years, as shown above it will be just as important to monitor Pakistan as a whole. Each province’s violence suggests the highly regionalized nature of conflict and risk in Pakistan, but also the key linkages between its regions. ACLED recorded a large decrease both in event count and reported fatalities in Pakistan from 2015 to 2016. As laid out above, much of this shift can be accounted for by the targeting of militants in the frontier regions, which has pushed many of them to the cities. As 2016 has demonstrated, this has meant an increase in large-scale attacks in the Pakistan’s major cities, including Karachi, Lahore and Quetta, which will likely lead to a shift in the focus of the security forces back to these cities which are increasingly at the centre of Pakistan’s economy and politics.