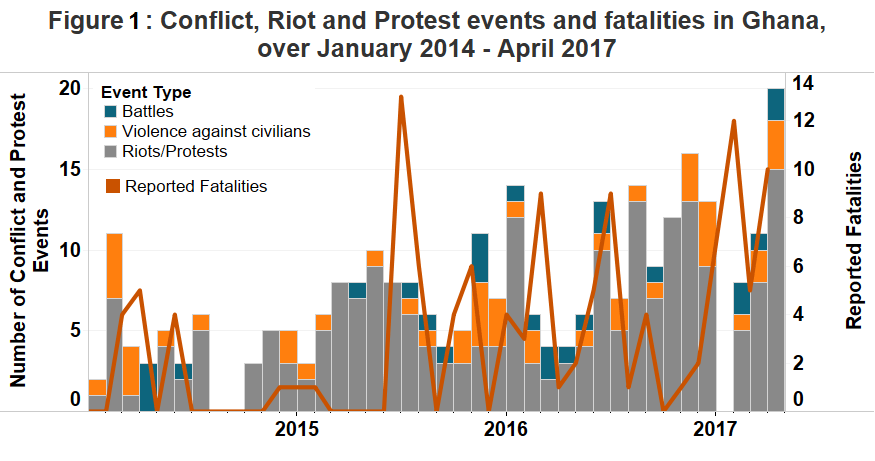

Political violence in Ghana has risen sharply since the beginning of 2017. While Ghana is among the least violent places in both West Africa and the continent at large, recent internal developments raise concern. They reveal widespread dissatisfaction among the ruling party supporters with the new regime, but also the latter’s inability to control the violence.

This upward trend in political violence has been mainly driven by riot episodes throughout the country (see Figure 1). One main issue since president Nana Akufo Addo, from the New Patriotic Party (NPP), took office end December 2016, has been the rejection of his regional and district appointees by NPP supporters. Through protests and riots across several regions from as early as February, NPP supporters expressed frustration at the lack of participation of these appointees in the party’s electoral success. In the Ashanti region in particular, riots were led by an NPP-affiliated gang under the name of “Delta Force”, who played an important role in ensuring security and support for local party officials during the campaign and was expecting rewards in the form of government appointments among their ranks (GIN, 12 April 2017). As these appointments did not materialise, they felt neglected. On 24 March, the gang stormed the premises of the Regional Coordinating Council in Kumasi, destroying public property and manhandling the new Ashanti Regional Security Coordinator, whom they did not support. Two weeks later, the group freed its fellow members charged after the first incident by attacking the Kumasi Circuit Court (AFP, 12 April 2017). Protests and riots by NPP youth expanded to Ashanti’s neighboring regions and to the northern part of the country following these events, involving the vandalizing of party offices.

Two main elements raise the risk that an armed resistance emerges against the regime if not properly tackled: first, discontent vis-à-vis Akufo Addo’s ability to implement his ambitious electoral agenda to fix economic issues and corruption in Ghana (Independent, 18 March 2017); second, the very existence and expectations of these party-affiliated youth gangs. This is even more true as around 20 such gangs are said to exist throughout the country. Several countries in the region, such as Sierra Leone and Ivory Coast, have witnessed similar trends in the past (Ghana Web, 18 April 2017).

Other riots also expressed an increased tendency among populations to resort to violence to resolve issues of discord and to take law into their own hands. In Bimbilla (Northern region) for instance, youth burnt houses and stormed the police station after a murder in the context of a chieftaincy clash, asking to be handed the suspect (Daily Guide, 10 March 2017). In Half-Assani (Western region) and Wa (Upper West), people rioted against police to protest the latter’s involvement in cases of death in custody or on roads (Myjoyonline, 2 April 2017). Finally in Adina (Volta region), local angry youth besieged and damaged property at a salt company to protest harassment and drying up of water sources, leading up to a clash with police that left one person killed (GNA, 20 March 2017).