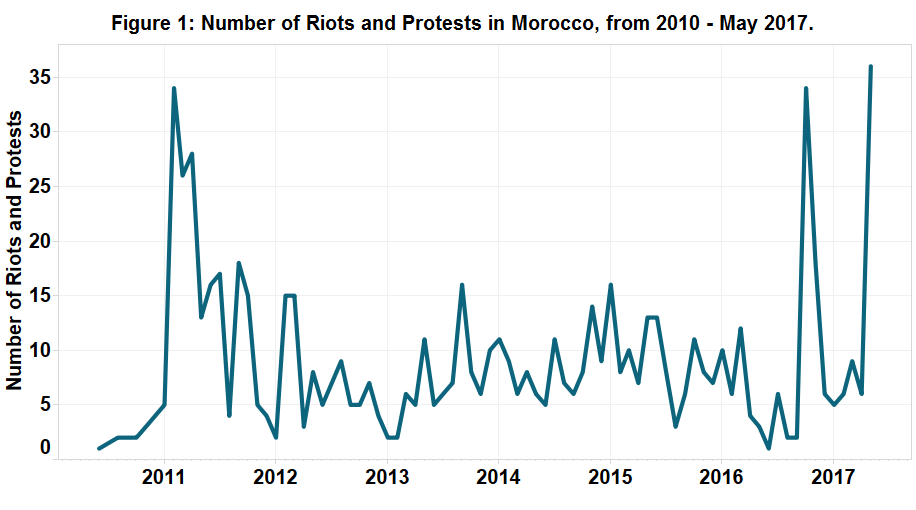

In May, Morocco experienced the highest rate of protests recorded in the ACLED dataset (see Figure 1). Tensions erupted in Al-Hoceima in northern Morocco in late October 2016 following the death of a fishmonger in a garbage truck. Police had confiscated his goods and he was crushed to death attempting to retrieve them. The event struck a chord with the local population in the historically marginalised Rif region and initial protests in late October 2016 centred on a wide range of grievances from justice against police abuse to socio-economic development and have in some instances evolved to denounce corruption against the regime.

Last month, protests in Al-Hoceima and surrounding areas intensified and spread to Marrakesh, Nador, Oriental, Tangier and the capital Rabat leading to questions over the potential for protests to spread nationally. Some have pointed to the underlying ethnic nature of the Rif protests, a predominantly Berber region and how this could hinder national mobilisation (Mekouar, 5 June 2017). Others have identified how many regions in Morocco share similar grievances to those expressed in the Rif movement (Masbah, 29 May 2017). Historical strategies of the state combined with current developments in protest behaviour and internal party dynamics offers one way to interpret the processes that could shape the trajectory of the protest movement.

The Moroccan regime of Mohammed VI has traditionally employed a mixture of concessions and repression, courting the interests of potential challengers, and incorporating groups into a nominally open but contained political system. For example, during the 2011 constitutional reform process, the King effectively dismantled the momentum behind the February 20 Movement and subsequent mobilisation by reincorporating divided political parties back into the regime severing their alliances with the popular movement (Abdel-Samad, 2014). The regime has tended to employ repressive tactics when protest demands move beyond specific reform policies that the King can address and into more general calls for democratic openings. For example, the state has routinized the performance of protest by unemployed graduates in Rabat seeking jobs (Badimon, 2013) amongst many others negating the need for repression.

The reason for this mixed strategy is to deter the escalation of demands and wider appeal nationwide and for groups to accept concessions. The state did not violently engage with the initial October 2016 protests, allowing them to unfold peacefully despite clustering in a restive region. Repression in Al-Hoceima significantly increased in May 2017 (see Figure 2) and the arrest of the de facto leader of the Hirak (Popular Movement) – Nasser Zefzafi – has sparked further protests. This in part can be understood by Zefzafi’s refusal to negotiate with the regime. Therefore, the challenge to the monarchy, despite being regionally-contained in the Rif, would not have sat well with Mohammed VI especially after a delegation led by the Interior Minister visited Al-Hoceima in late May in a gesture to boost investment in the economy.

The detention of Zefzafi poses two possible trajectories:

- Zefzafi has been replaced by two women leaders. If the new leaders of the Hirak (Popular Movement) are willing to negotiate with the regime then the protesters may be accommodated before threatening to spill over into other areas with similar grievances. Therefore, support for the protest movement will gradually decline as grievances are appeased and the opportunity-cost to mobilise increase (protesting likely hit with repression as King has extended concessions).

- However, precisely because of this new leadership, there is an opportunity to extend the appeal of the Rif protests beyond the North-West region. Zefzafi’s narrow Berber appeal, misogynist views, crude tactics and lack of education (Al Jazeera, 4 June 2017) would potentially have divided rather than united a popular movement.

Regardless of these two possible pathways of protest, having offered an economic concession to the region and decapitated the movement ‘leadership’, the monarchy would expect the protesters to accept the terms of negotiation. Any repression that does occur is likely to be swift, targeted and aimed at preventing backlash and cutting it off from national support and wider political appeal.

After the King removed Prime Minister Abdelilah Benkirane after five-months of deadlock in forming a coalition government, he appointed another member of the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD) – Saad-Eddine El Othamni as leader. Seen as more of a technocratic politician, the replacement led to the almost immediate formation of a coalition government. This has in many respects appeared to consolidate the Palace’s hold on power by incorporating palace allies into the coalition government and limiting the increasingly popular PJD under Benkirane which was seen by some to pose a threat to the Makhzen’s strategy of governance.

It may however have provoked internal discontent within the party apparatus. Notably, the PJD has called for a hearing on police conduct during the protests (Morocco World News, 3 June 2017). Similarly, the Istiqlal party — a nationalist party long accused of discriminatory policies towards non-Arab communities in Morocco (Agoravox, 17 October 2014) recently voiced support for the protests. Taken together, these two dynamics are potential signals of resistance for the King from within the established ruling and opposition elite which could benefit the momentum behind the Rif protests and lead to further protests throughout the country.