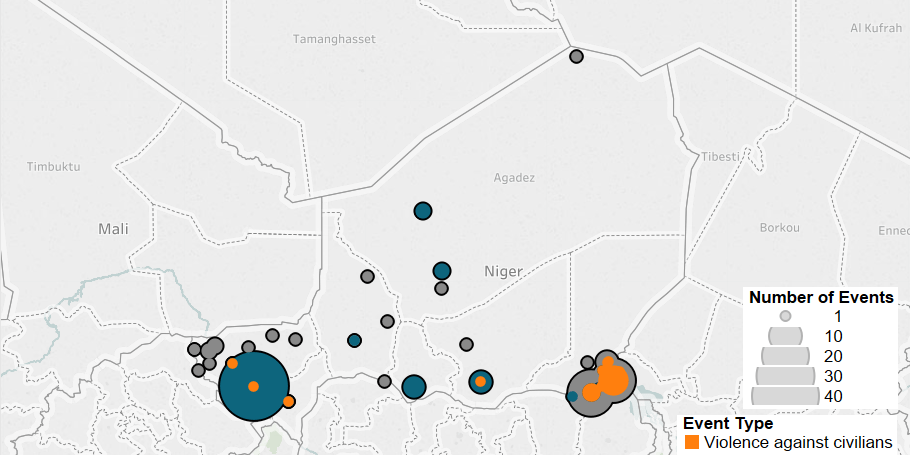

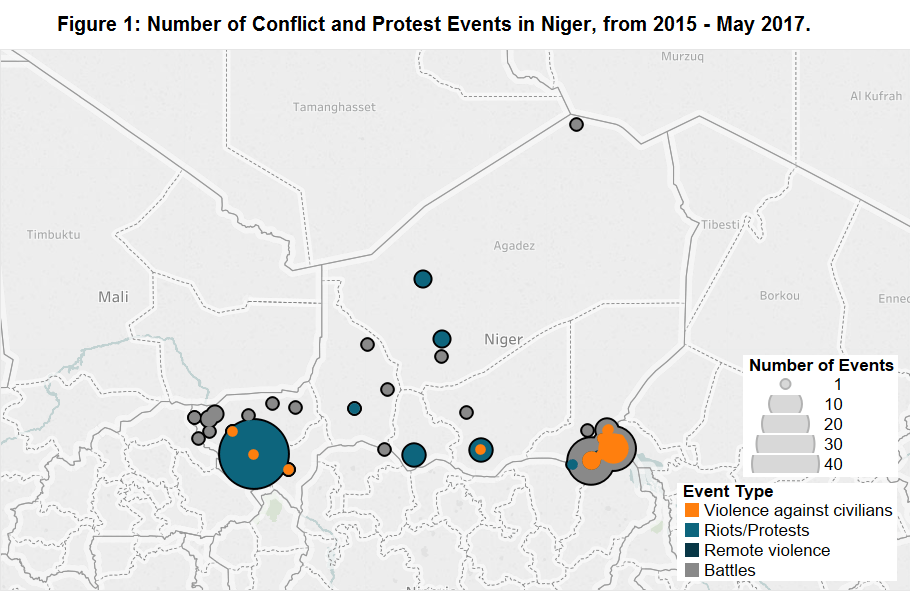

Violent activity in Niger has been sporadic over the last year and half, and its political nature has been generally divided by region. As the sparsely populated north east has remained nearly untouched over the recent period, the western areas, including the capital and along the south-east border of Nigeria’s Boko Haram stronghold of Borno State have had presence of protest and battles, respectively.

In the country’s southeast, Boko Haram has launched excursions into the Diffa Department along the N1 Highway’s southern loop (see Figure 1). Situated along Borno State to the south, Boko Haram often uses armed squads and buried IEDs to attack state military convoys travelling in the area. Attacks along border towns, primarily Diffa and Bosso, remained fairly consistent until the late 2016 – early 2017 collapse of Boko Haram’s core operations within Sambisa Forest of Nigeria (The Guardian 24 December, 2016). As a result, only four instances of Boko Haram activity occurred in the region since the beginning 2017; the most notable being a substantial defeat at the hands of the Chadian and Nigerien militaries, which led to 57 Boko Haram fatalities at Gueskerou in April (Reuters, 10 April 2017). Overall, future success for the group in Niger will likely depend on new core organizational efforts in Borno, Nigeria.

To the northwest, most activity has been concentrated along the flow of the Niger River, primarily in Tahoua and Tillaberi Departments and the capital, Niamey. Here, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Ansar Dine – who, along with the Macina Liberation Front and Al-Mourabitoun, merged their organizations in March 2017 becoming Nusrat al-Islam (Africa News, 3 March, 2017) – are active insurgent actors, ambushing gendarmeries in rural areas along the shared border with Mali. A somewhat recent development from late 2016 is the presence of the Islamic State cells in this same area, again targeting police patrols. This development is somewhat unsurprising, as several AQIM splinter groups pledged allegiance to Islamic State in 2014 (Religion and Politics, 8 October 2014). Broadly, the majorities of these attacks are small in scale, infrequent and yield low fatalities. However, the geographic area of activity is relatively vast compared the size of their force, perhaps an indicator of their spreading influence in the region.

Although activity among these groups has been a multi-regional phenomenon, protest action has primarily been centred in Niamey (see Figure 1). These demonstrations have largely been non-violent labour movement related protests. In rare instances of protest action outside the capital, demonstrations are often related to security concerns, such as in reaction to insurgent attack. It stands to reason these protests will become less frequent in the short term as Boko Haram’s presence in the southeast diminishes.