The first half of 2017 has seen Tunisia going through one of the deepest political crises in recent years. Widespread popular protests have flared up in the country’s inner regions, severely hitting the domestic production of oil and gas. A government-sponsored judicial investigation resulted in the arrest of well-known politicians and businessmen, accused of corruption, embezzlement and threatening national security. Armed Islamists operating in mountainous areas in the west of the country continue to pose a serious threat to civilians despite the enduring state of emergency. At the same time, weak economic recovery and protracted partisan bickering mar the government of 42-year-old Youssef Chahed, limiting its capacity to tackle the country’s acute problems effectively.

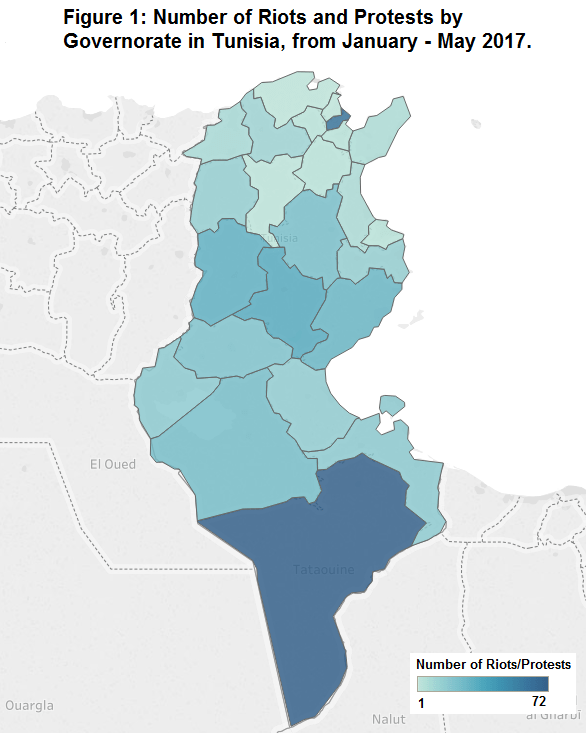

Since the beginning of the year, Tunisia has witnessed a marked increase in the number of riots and protests recorded by ACLED. Large-scale protest movements have taken place across the country, involving long-restive and traditionally quiet governorates alike. The south-eastern region – comprising the governorates of Gabes, Medenine, Sfax and Tataouine – accounted for almost one third of all protest events between January and May, followed by the governorates of the centre-west and the north-east of the country (see Figure 1).

Whilst the grievances driving the demonstrations have not changed since 2011 – high youth unemployment, anaemic socio-economic development, political marginalisation – these have become ever more acute as the absence of tangible improvements became apparent and long-standing industrial crises went unresolved. Last January, protests near the industrial areas and the mining basins of Sidi Bouzid and Gafsa escalated into violent riots when the demonstrators erected roadblocks and engaged in stone-throwing against the police (Reuters, 14 January 2017). Starting from late March and throughout April, thousands of residents took to the streets in the north-eastern province of Le Kef to protest the relocation of a local manufacturing plant to the coastal town of Hammamet, which would require the layoff of 430 employees (Kapitalis, 30 March 2017; Le Monde, 20 April 2017).

Popular unrest has most notably rocked in the southern governorate of Tataouine, a scarcely populated province whose economy is highly dependent on natural resources extraction and informal cross-border trade with neighbouring Libya (International Alert, December 2016). Since March, the local population has protested demanding that the region’s energy revenues are used to promote jobs creation and development. Demonstrations have rapidly spread from the town of Tataouine to remote villages and the desert oil sites, where demonstrators have blocked roads and camped out for weeks bringing oil and gas production to a halt (Reuters, 8 May 2017; Jeune Afrique, 2 June 2017). In the ensuing attempt of breaking up the protest camps, a National Guard vehicle “accidentally” ran over a protester in Oued El Kamour, leading to his death and sparking outrage among the demonstrators (Al Jazeera, 22 May 2017).

The turmoil in Tataouine has had major repercussions on national politics, forcing the government to take exceptional measures for the region and stoking tensions between political parties (Tunisie Numerique, 10 April 2017; Realités, 23 May 2017). However, these events were further brought on the spotlight following a judicial investigation that resulted in the arrest of the businessman Chafik Jarraya, the former presidential candidate Yassine Channoufi and a number of other businessmen, politicians and government officials on charges of corruption and threats to national security (Jeune Afrique, 24 May 2017). According to media sources, Chafik Jarraya – a well-known tycoon with vast financial interests in Tunisia and Libya and strong political connections domestically and abroad – is accused of financially supporting protest movements in Tataouine and across the country (Business News, 23 May 2017; Jeune Afrique, 30 May 2017). The investigation has thus unveiled an extensive network of corruption, revealing how second-tier political and economic elites are willing to stir up unrest in an effort to influence the political process for personal gain.

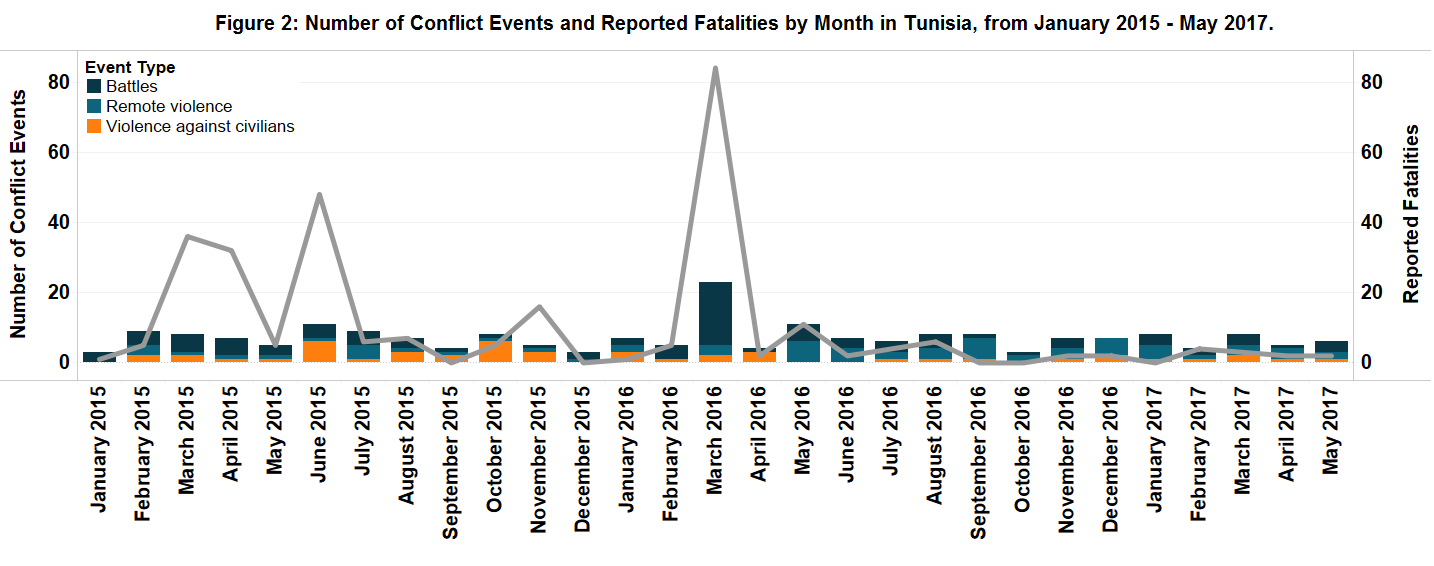

Following the Islamist offensive on Ben Gardane in March last year, Tunisia has managed to avoid other major attacks on its territory. Conflict fatalities have significantly decreased compared to previous years, and are largely limited to armed clashes between armed militants and security forces in the west of the country (see Figure 2). These trends notwithstanding, the active presence of militants groups in the heights of Kasserine – Jebel Chaambi, Jebel Mghila and Jebel Semmama – continue to breed insecurity among the civilian population. Landmine explosions have injured and killed several shepherds over the past few months, while militants frequently raid civilian homes in search of food. In the latest episode of violence, the Tunisian branch of the Islamic State claimed the assassination of the young shepherd Khalifa Soltani, the brother of Mabrouk who had in turn been killed and beheaded in November 2015 in the same area (Mosaique FM, 3 June 2017). Although the prime minister has pledged to support Soltani’s family, the government is widely perceived as unable to promote local development and protect communities living in isolated areas from armed militants (Inkyfada, 28 January 2016).

Tunisia is currently facing multiple, intertwined challenges. Economic stagnation and political marginalisation have fuelled widespread frustration across the regions in inner Tunisia. Endemic corruption continues to pervade national and local politics, fostering distrust in the government and the political parties. Despite declining activity, armed militants continue to threaten civilian lives in remote areas. Shaken by persistent instability – three cabinet reshuffles have occurred in less than ten months – and with limited financial leeway, the coalition government is criticised for failing to live up to its promises and push through effective reforms (Le Point Afrique, 12 April 2017; Tunis Afrique Presse, 15 May 2017). Hence, in absence of palpable improvements, Tunisia will likely continue to see sustained popular mobilisation in the coming months.