On 24 August, before counting finished, it was announced that the MPLA had won the majority of the parliamentary seats in the Angolan election. The MPLA candidate, Joao Lourenco, won the presidential vote (The Guardian, 24 August 2017). There has been significant commentary that this election does not alter the politics of Angola. Jose Eduardo dos Santos stepped down after 38 years in power, but chose Lourenco, Minister of Defense and MPLA Vice President, as successor. Prior to leaving, dos Santos passed a bill protecting security figures from dismissal, and he promoted his daughter, Isobel, to chair Sonangol (Financial Times, 20 August 2017).

However, even given allegations of fraud – four opposition parties issued a statement demanding a re-count (Maka Angola, 4 September 2017) – the MPLA was less successful than it has been previously. The ruling party won 150 of the 220 seats, compared to the 175/220 won in 2012 and the 191/220 won in 2008 (Al Jazeera, 25 August 2017).

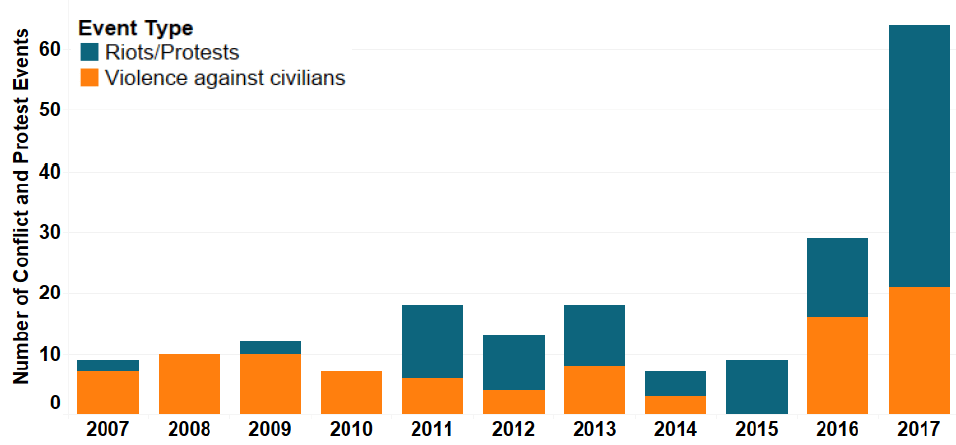

Moreover, 2017 has seen nearly five times the level of protest that was seen during the last election year, 2012 (see Figure 1). (Confidence in the exact number of protests over time is limited because of significant barriers to reporting). Dissidence is suppressed: protesters and journalists are often imprisoned (All Africa, 24 August 2017), on 12 August, demonstrations by groups not running for election were banned (Human Rights Watch, 16 August 2017), and the state media accuses UNITA of using demonstrations to return the country to war (Business Day, 23 August 2017). Nevertheless, protest continues to grow. In June, UNITA marched for free and fair elections. Four thousand people demonstrated in Luanda (News24, 3 June 2017), and many hundreds more in Benguela, Huambo, Lubango, Menongue, Namibe, and Sumbe.

Many protests this year focused on economic issues: there were a number of actions from teachers and government employees demanding unpaid wages, there were also a number of protests against industries (FCKS Cement Company and Somipa Mine). The close links between the business elite and the political/military elite mean that economic protest is just as much an expression of frustration with the MPLA and state as political protest. The leadership of FCKS Cement, for instance, is closely linked to the MPLA and military (Maka Angola, 25 September 2015).

There has also been a rise in localised protest in the Lunda area, by groups demanding autonomy for the region (Maka Angola, 27 June 2017). An increase in localized activity was also reflected in the slight increase in reports of violent clashes in Cabinda. The FLEC rebels called for a poll boycott in Cabinda (International Business Times, 13 February 2017). The political status quo may not have altered significantly on 23 August but the rise in protest is an important signal for Angola’s opposition.