Which group is the most violent in Africa? A recent report exploring Africa’s active militant Islamic groups aimed to tackle this question. The report, produced by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies (ACSS), argued that Somalia’s Al Shabaab has eclipsed Nigeria’s Boko Haram, to become “Africa’s deadliest group”. The claim was supported with data drawn from ACLED.

While this superlative has been cited by a number of news outlets (including Quartz, Vice News, and Newsweek) since it was published in April 2017, its foundation was recently challenged by an article by Salem Solomon and Casey Frechette. Solomon and Frechette argued that ACSS’ conclusions are the result of choices made during their analysis of ACLED data, which, they argue, are not robust. They assert that, when considered in terms of who did what and to whom, it is Boko Haram, not Al Shabaab, who has killed far more people.

A closer look at the ACLED dataset reveals that: both are correct. This is not simply a semantic discussion, or one based on academic definitions: it reminds us that it is important to recognize what conflict data can and cannot do before drawing conclusions from them. This is especially true, given the impact these conclusions may have on foreign policy, as Solomon and Frechette accurately note.

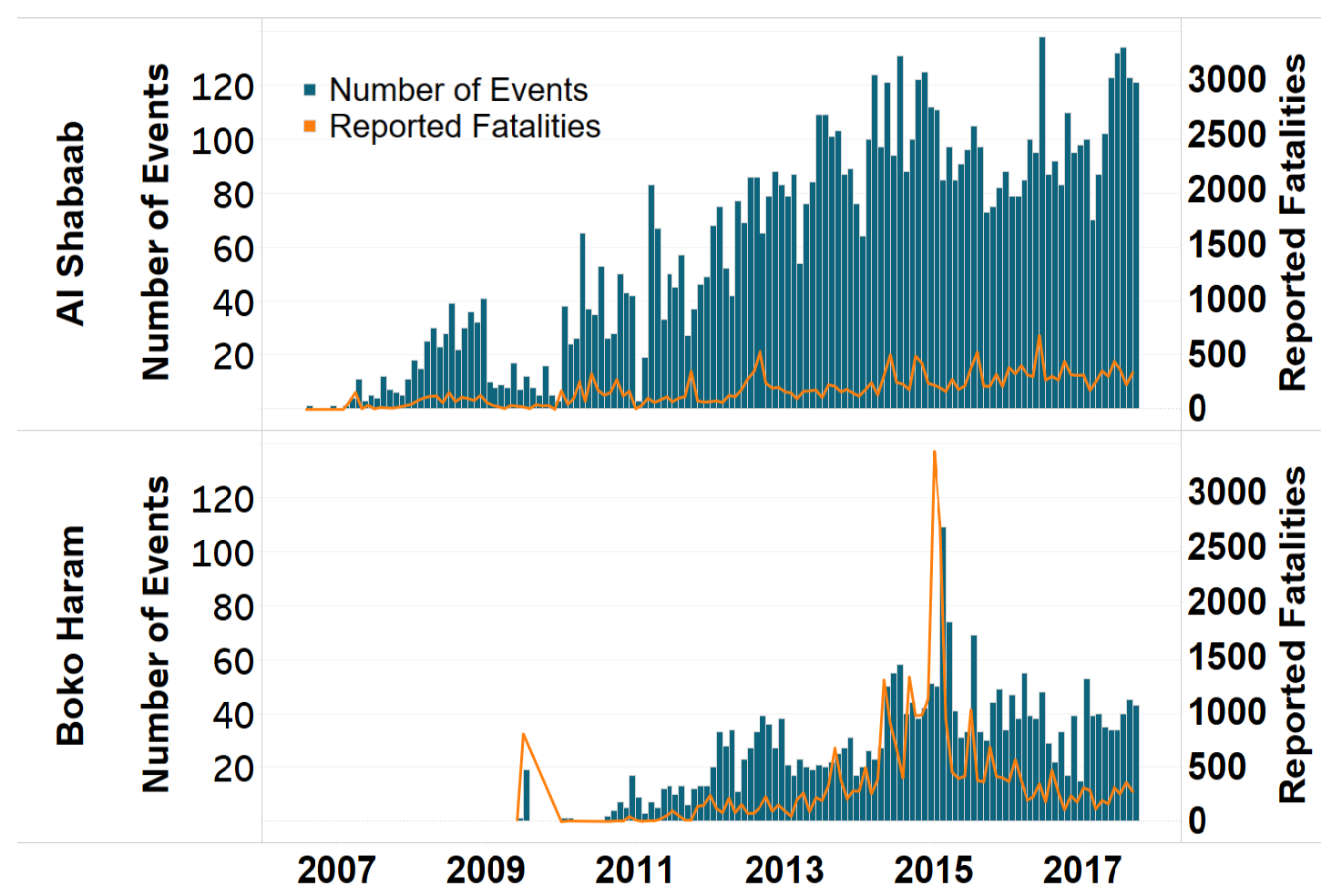

So, how can both groups be considered the “deadliest”, a label that is normally afforded to only one? A closer look at the data for both groups can help to shed some light. According to ACLED data, in 2016, Al Shabaab was involved in the most violent events (911) in Africa, resulting in a total of 4,282 reported fatalities for those events. Boko Haram was the 6th most violent armed organized group in Africa in 2016: involved in 419 events resulting in 3,500 reported fatalities. However, the ratio of events to reported fatalities suggests that while over 4 people were killed in every Al Shabaab attack, more than 8 people were killed in each Boko Haram attack. To further complicate matters, on average, twice as many people are killed (on both sides) during battles involving Al Shabaab than when they target civilians, whereas reported fatalities associated with Boko Haram do not significantly vary depending on what type of event they engage in. Finally, Boko Haram has certainly declined as a force in the past eighteen months: they are smaller, weaker, scattered and often operating on foreign soil (Cameroonian events are included in this analysis). In contrast, Al Shabaab has gained significant strength and territory during the same period.

In determining “Africa’s deadliest group”, the authors of both pieces assumed that ACLED data identifies who killed whom. But, they do not, and no data reliably do. In studies of conflict and violence reporting, the “who, what, where, and when” is often correct and easily confirmed and corroborated. Problems often emerge when people want to know “why?” or “how many?”. Conflict reports come in from rural frontlines, urban slums, border regions, private property and many other types of locations. Reporters are not there to relay the details; they must rely on sources that — more often than not — are involved in some way in the conflict and, therefore, are biased to a certain degree. Indeed, even studies that are based on police records, hospital admittances, cemeteries, etc. fall victim to this phenomenon. Effectively, conflict data can tell us what happened, but not much more.

Unfortunately, for researchers, policymakers, and those affected by conflict alike, what conflict data cannot tell is considerable, and consequential: it has real world impacts that must be understood and factored into our analysis and commentary accordingly.

Fatalities and Casualties

Fatality numbers are the most biased, poorly reported component of conflict data, making them, overall, the most susceptible to error. They are often debated and can vary widely. With exceptions, such as events where unarmed civilians are killed, there is no way to reliably discern which armed, organized group kills more or fewer members of the group(s) they fight using ACLED data. There are incentives for conflict actors to over- or under-report fatality numbers. In some cases, over-reporting of fatalities may be done as an attempt to appear strong to opposition, while in others, fatalities perpetrated by state forces may be under-reported and those by rebels over-reported, in order to minimize international backlash against the state involved. There may also be a systematic violence bias in mainstream news reports where fatalities are over-reported in order to increase media attention. There are contexts, too, in which fatalities may be under-reported as a function of the difficulties of collecting information in the midst of conflict.

While ACLED codes the most conservative reports of fatality counts to minimize over-counting, this does not account for the biases that exist around fatality counts at-large. Furthermore, the true cost of conflict cannot be measured by deaths on a “battlefield”. Conflicts that may result in fewer deaths on the battlefield still contribute to instability and fragility. For example, conflict can impact food security, which can in turn result in large numbers of fatalities – as seen recently in South Sudan. Conflict can also damage health infrastructure which can result in future vulnerability to health pandemics – as seen in Liberia, where over half of its medical facilities were destroyed during the Liberian Civil War, leaving the country extremely vulnerable to the Ebola epidemic, which resulted in thousands of deaths.

Moreover, counting deaths on the “battlefield” is necessarily “biased towards men’s experiences of armed conflict to the detriment of those of women and girls” as Bastick, Grimm, and Kunz point out in a report. This is because while more men may be killed while fighting, women and children are often the victims of other forms of violence during conflict (e.g. sexual violence).

And so, while it is certainly important to report the death and destruction imposed by armed groups, it is wrong to gauge the impact of these groups based on numbers that data providers explicitly acknowledge as both questionable and inadequate to capture the true impact of conflict.

Group labels and motivations

Some research treats the perpetrators of violence differently. Labelling groups with mantles such as “terrorist” or “insurgent” presumes a distinct goal, motivation, modality and target. We think that labels often legitimize or delegitimize activity, and strongly believe that terrorism is an event where people are killed who are not expecting to be risking their life at that time. But, because beliefs, intentions and expectations are not possible to parse in our quantitative data, to use such labels would distort, rather than inform, the debate. Further, who is considered a terrorist, and who is not, is a discussion that is pointedly political and has no basis in data. For example, many limit the definition of a terrorist attack to those carried out by a non-state actor; however, many governments kill their citizens with greater frequency and in higher numbers than any non-state organization. Are these “terrorist” governments? Where you stand on that depends on where you sit politically.

Risk to whom?

Determining how “deadly” a conflict group is is essentially a proxy to assess the risk that a group poses. Yet the risk associated with a conflict group is multi-faceted and cannot be reduced to the number of fatalities they are allegedly responsible for. This is because, not only are fatality counts unreliable as discussed above, but also they fail to capture a number of important dimensions of risk.

The ‘risk’ associated with a group can be gauged by observing a wide range of indicators including, how much violence it commits or the lethality of these events (see Figure 1); however, it is not limited solely to these factors.

The risk associated with a particular group, especially vis-à-vis others, can also be gauged by considering in how many distinct places they commit violence, over what period of time they are active, with whom they interact, and what their activity is relative to other armed, organized actors. Using all of these measures concurrently, a researcher can assess whether a certain group is a larger threat to the state or civilians than other groups. Fatalities, or incidents of violence, alone do not paint the full picture.

When considering these many facets of risk, the difference in the risk profiles of Al Shabaab and Boko Haram is clear. Al Shabaab has had, over its active period, a relatively low rate of civilian targeting, when compared to other groups in similar positions (see Figure 2). (That being said, for many years, ACLED analysts have suspected that Al Shabaab employs unidentified armed groups to kill civilians for them, and to perpetrate many of the less popular acts which take place in the insurgency.)

Rather than target civilians, their strategy is to be the Al Shabaab that is simultaneously the business innovator, the local militia, the job creator, the dealmaker, the negotiator and the parallel government (read: taxing force).

Somalia is “functioning” as a system where violence is an accepted reality. This may be due, at least in part, to the relatively low rate of violence against civilians as a proportion of Al Shabaab’s overall violent activity: at 11%, it is 20% lower than the average rate of civilian targeting (as a proportion of activity over time between battles, remote violence, strategic developments, and civilian targeting). Further, civilian targeting has never been a large part of Al Shabaab’s repertoire (an average of 11% of total activity and over 14% in 2016).

In contrast, nearly 31% of Boko Haram’s activity this year has been directed towards civilians, reaching a nearly 47% high in 2014 and decreasing to less than 24% in 2016.

By accounting for the multidimensionality of risk in assessments about groups, one can better understand the nature of a threat. So, for example, while civilians may be at higher risk of death at the hands of Boko Haram relative to Al Shabaab, Al Shabaab may pose a higher risk to stability in the region given the nature of its activity. This instability may in turn result in a severe negative impact on civilians. Limiting analysis to purely fatality numbers would miss these important dynamics.

How do groups shape the conflict environment?

The trends and statistics noted above are informative, but Al Shabaab and Boko Haram are two very different groups and contrasting them and the conflict environments they create may not be so useful. Both Nigeria and Somalia would be very dangerous places without Boko Haram or Al Shabaab, respectively. Both groups have helped to create political environments where violence is dominant, and the state appears unable to prevent it.

In Nigeria, the threat of Boko Haram to the population is reduced when considering the large size of Nigeria’s population and hence the population at risk (the one-in-a-million [or micromort] risk of conflict-related death to civilians in Nigeria in 2016 [at the hands of any armed actor] was 0.03). However, their influence is vastly increased when considering what this violence, and the Fulani violence in the Middle Belt, says about the administration of the state: that the state does not, in fact, have a monopoly on violence in Nigeria.

In Somalia, Al Shabaab has not been successful in preventing the formation of a state, but the fact that 128 armed organized groups were active last year in Somalia suggests that non-state groups have yet to be convinced of the benefits of having a state.

While far fewer civilians were reportedly killed in Somalia versus Nigeria last year (894 versus 2,086, respectively), when accounting for the fact that the population of Nigeria is almost 13 times larger than Somalia, this difference is not so stark. In fact, the one-in-a-million (or micromort) risk of conflict-related death to civilians in Somalia in 2016 [at the hands of any armed actor] was 0.17 – which is over 5 times higher than that seen in Nigeria, suggesting that the average civilian is at higher risk of conflict-related death in Somalia than in Nigeria.

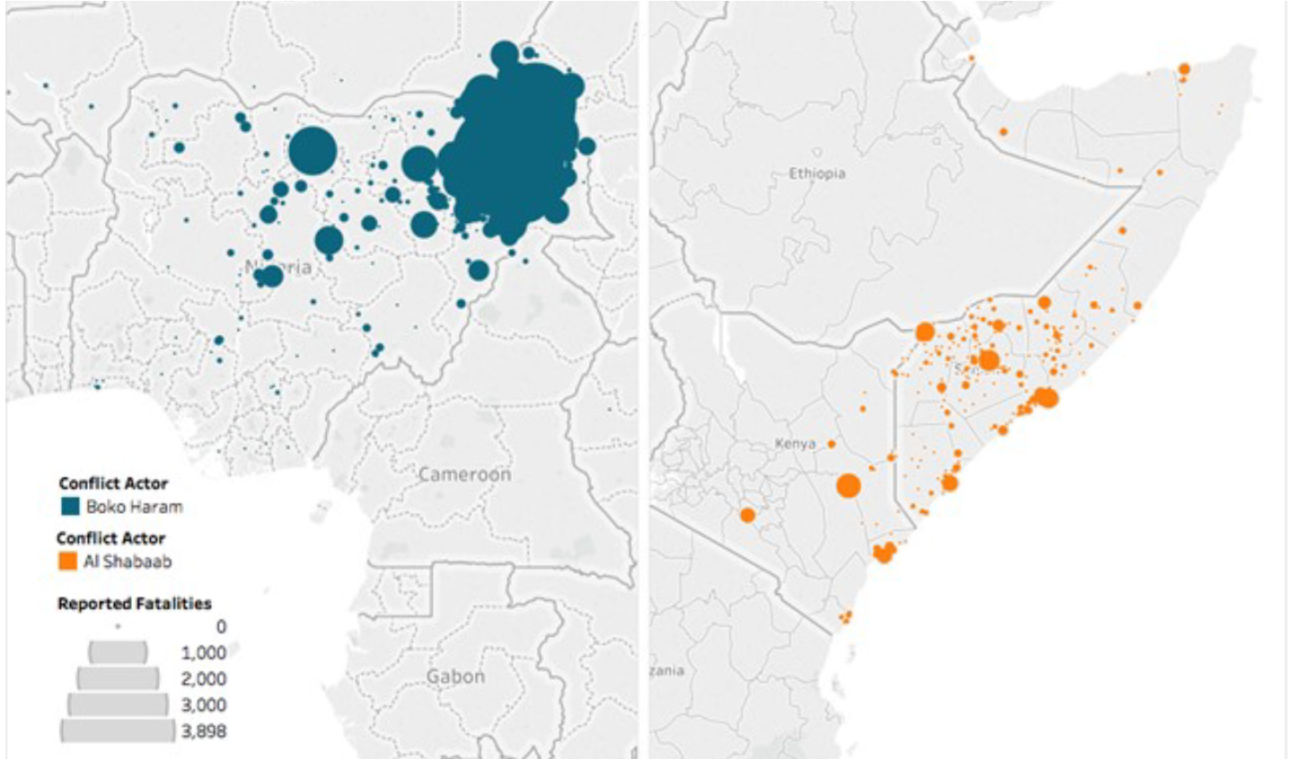

One key difference between these two groups comes down to effectiveness: Boko Haram is not very good at challenging the state and offering itself as an alternative government option, while Al Shabaab has excelled at this. The scope of their activities also differs. While reported fatalities involving Boko Haram have been spatially limited to north-eastern Nigeria near the country’s borders, reported fatalities involving Al Shabaab have taken place across the majority of Somalia (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Reported Fatalities from Conflict Involving Al Shabaab and Boko Haram, August 2006 – September 2017

Statements about the “most” or “least” anything when it comes to conflict should always be made with caution as they, by definition, only point to one dimension. Furthermore, employing fatality counts to support these kinds of unqualified statements is inherently problematic due to the shortcomings of these metrics, as explored here.

Beyond the potential biases of fatality counts, however, is the fact that they represent only one perspective on risk. Even if fatality data were “perfect”, they still would not illuminate the true risk that a group may have for populations in the areas in which it is active. Focusing on these tallies ignores a wide range of indicators, which can help us to gauge the risk associated with a particular conflict group, and how their activity compares to other armed, organized actors. Finally, these points have particular bearing outside of academia and specialized conflict research in so far as fatality counts are used to support claims about “deadliness”, danger or risk of particular conflict actors, especially relative to others, which are in turn consumed by the media, and policymakers as a result.

An abridged version of this report, in collaboration with ACSS, was featured in the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage on 2 October 2017.

Authors: Prof. Clionadh Raleigh, Dr. Roudabeh Kishi and Olivia Russell