January 2016 began a string of violence by militant Islamist groups in West Africa that moved beyond the “arc of insecurity” reaching from Mali in the north to the Lake Chad basin in the east. This first attack was carried out by the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Al-Mourabitoun group on a hotel and restaurant frequented by foreigners in the Burkinabe capital of Ouagadougou, resulting in the reported deaths of 3 militants and 30 civilians (CNN, 18 January 2016). This attack would be followed only two months later in March by an assault by Al Mourabitoun and Al-Qaeda, this time on the resort town of Grand-Bassam in Côte d’Ivoire, leaving 16 civilians and 6 militants dead (BBC, 14 March 2016).

Although neither of these countries would see any comparable follow-up attacks in 2016, by the end of the year several other militant Islamist groups had engaged in smaller attacks in Burkina Faso. These included two claimed by the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and one by an unidentified Islamist militia from Mali on security posts in the country’s north. However, these attacks were overshadowed by an attack in December 2016 on an army post in Nassoumbou by around 40 heavily-armed gunmen, resulting in the death of at least 12 Burkinabe soldiers (MENASTREAM, 3 January 2017). This attack was claimed by a new group associated with both Al-Qaeda and Ansar Dine, Ansarul Islam, which announced its formation along with the claim shortly after the attack (Dakaractu, 4 January 2017).

Since these attacks, Burkina Faso has seen an upward trend in the number of battle and civilian attacks attacks and fatalities. Fatality levels are at levels matched by the 2014 ouster of President Blaise Campaore in 2014, and those from the discovery of a mass grave in February 2002. Although the total reported fatalities remain fairly low (see Figure 1) when compared with monthly totals from Mali or Nigeria, the increasing number of attacks by militant Islamist groups is the driving factor behind this rise and represents a significant spread of militant activity in the country. Events involving militant Islamist groups accounted for more than 75% of all fatalities reported in Burkina Faso in 2016 (58 of 81), while in 2017 they represented just fewer than half of all reported fatalities (40 of 90). And although their share of total fatalities fell, another third of all fatalities reported are attributed to unidentified armed groups which used violence either associated with militant Islamist groups in the area, such as planting IEDs, or which heavily overlapped with the operating areas of these groups.

Figure 1: Number of Events and Reported Fatalities by Type in Burkina Faso, January 2015 – September 2017

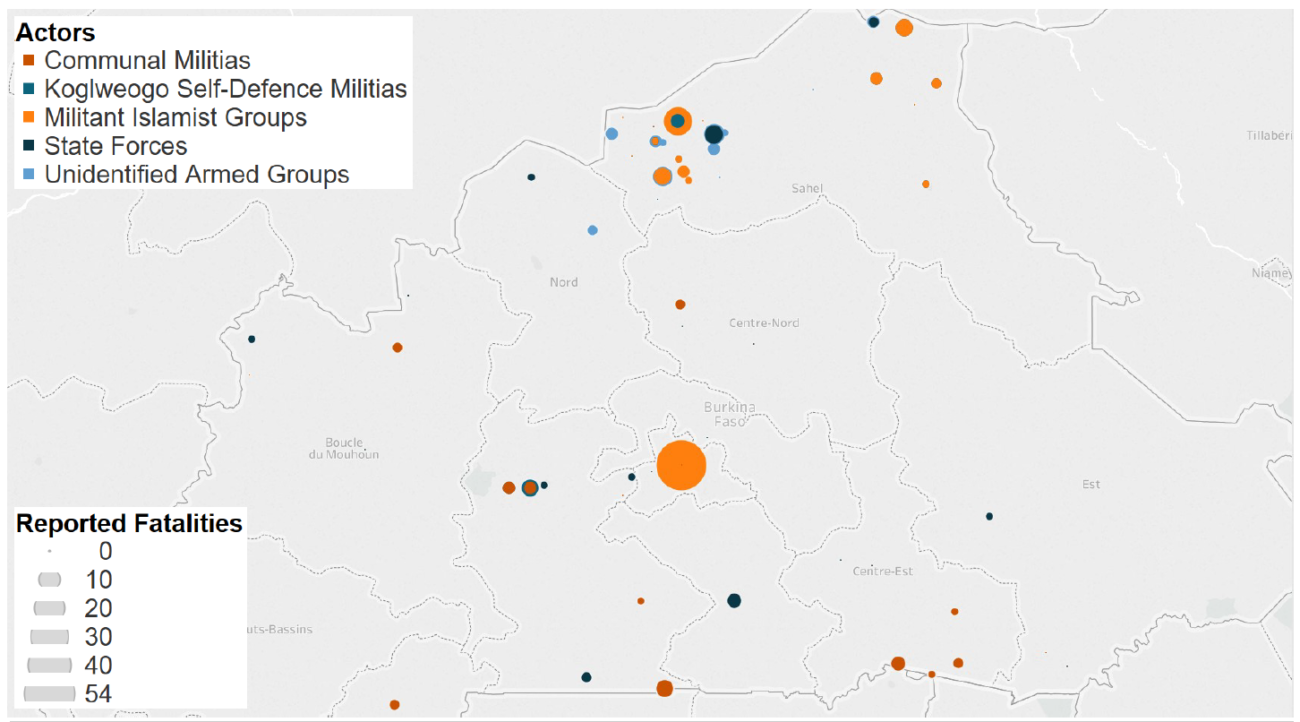

This last point is particularly important as the increasing violence recorded in Burkina Faso since the end of 2016 has largely been clustered in the northern Sahel province, with the majority of incidents occurring in the Oudalan and Soum regions bordering Mali and Niger (see Figure 2). These regions have seen almost all of the activity by militant Islamist groups and also the majority of violence by unidentified groups, suggesting that there is likely significant overlap. The clustering of these attacks on the border with Mali and Niger is not surprising given that cross-border attacks have also been relatively frequent in Niger since the beginning of the conflict in Mali. Discussions between the governments of Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger to develop a regional security task force, similar to the Multinational Joint Task Force dealing with Boko Haram, were actually motivated by the increasing incidence of cross-border attack (West Africa Brief, 6 February 2017), although with little success despite more recent French efforts to revive the idea (The National, 2 July 2017).

Another perspective on this rising violence by militant Islamist groups in Burkina Faso is the form it takes. Although both battles and violence against civilians have seen a proportional increase in 2017 over 2016, there have been additional dynamics within these trends, such as attacks on schools. Ansarul Islam’s specific targeting of schools and teachers has involved the militants showing up at schools and demanding the teachers instruct their students in the Quran and stop teaching French (France24, 20 March 2017), while in others cases, militants have gone as far as killing school principals and teachers (Xinhua, 4 March 2017). Ansarul Islam has also been the only group to engage in a large-scale attack outside of Sahel province since 2016. This attack took place between August 13-14, 2017 when militants from the group imitated the 2016 attack on Ouagadougou by assaulting another hotel and restaurant frequented by foreigners, resulting in 16 civilians and 3 attackers killed (The Guardian, 14 August 2017).

However, despite the persistent violence being carried out by militant Islamist groups in Burkina Faso, the upward trend in the country may be short-lived based on dynamics in Mali and Niger. Both countries saw significant decreases in reported fatalities in September, with Mali’s reported fatalities falling month-over-month from a high of 185 in June 2017 to a low of just 34 in September 2017. With overall violence levels falling in Mali, this has the potential to translate into a corresponding fall in violence in Burkina Faso based on diminished cross-border attacks.