Riots and protests witnessed an uptick in intensity in Cameroon in September as demonstrators voiced their opposition to perceived discrimination towards the Francophone regions of Cameroon. Relatively routinized opposition to President Paul Biya’s 35-year rule has coupled with calls for independence (VOA news, 1 October 2017) demonstrating the complex set of grievances that motivate citizens to take to the streets. The movement has evolved from a strike by teachers and lawyers over political and economic marginalisation but more recently other groups have weighed in to voice their dissatisfaction, including the Ambazonia separatist movement and groups opposing the detention of activists.

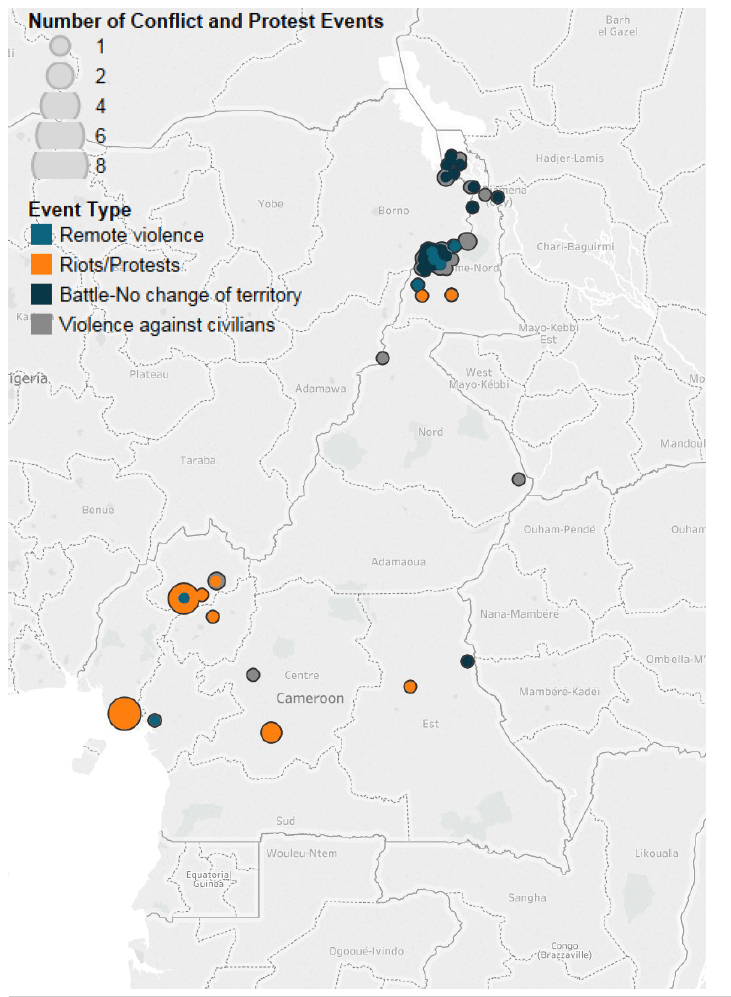

The months of November 2016, January and February 2017 experienced higher levels of protest than the February 2008 anti-government protests, with this trend largely driven by “dead-city” strikes in Buea and Bamenda (see Figure 1). Contention has been relatively contained to these two cities with the exception of September where unrest spread to Kumbo.

The government has taken a number of standard steps to quell the momentum of the protests. First, internet disruption has affected many parts of the Anglophone regions (Quartz Africa, 1 October 2017) as the government seeks to make mobilisation more difficult. This comes only recently after the region experienced a 93-day blackout when protests first began in January. Second, movement was restricted in Sud-Ouest Province – one of the English-speaking regions – and gatherings of more than four people were banned reminiscent of Museveni’s ban on public meetings in Uganda in 2012 (HRW, 11 May, 2012).

Third, although police dispersed protesters in November 2016 leading to clashes, repression declined in the following months. However, police repressed 60% of demonstrations in September compared to an average of 20% from December 2016 – August 2017. More unusually, the Rapid Intervention Brigade of the Cameroonian army deployed ahead of planned protests. Tensions culminated on the 1 October as seventeen people were killed nationwide, with at least eight people shot dead by Cameroonian soldiers during independence protests (Washington Post, 2 October 2017; BBC News, 2 October 2017).

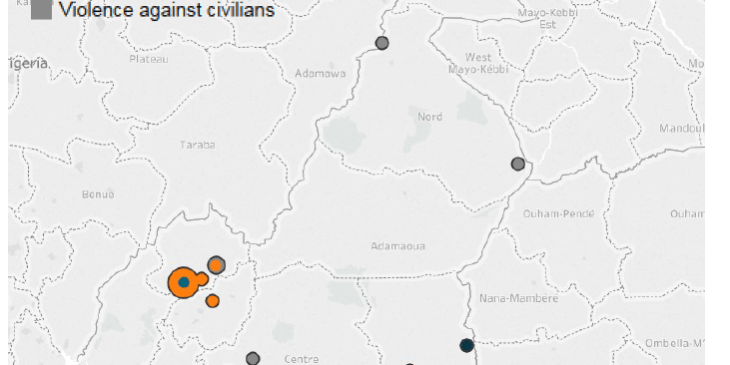

Security sources had justified the military presence at the protests to prevent episodes of violence, particularly “terrorist risks” as an IED exploded in Bamenda on 21 September injuring three police officers. Despite the bomb attack, fears of significant organised violence appear unfounded. Since November 2016, the majority of riot and protest events have taken place in Bamenda. Riots and protests in 2017 have concentrated in the south-west of the country, particularly in the Nord-Ouest and Sud-Ouest Provinces of Cameroon, whilst militant attacks have taken place overwhelmingly in the Extreme-Nord Province between Boko Haram militants and the Cameroonian army. Rather than overlapping conflict environments, very distinct geographies of political violence characterise Cameroon (see Figure 2). Therefore, further escalation of tensions are likely to be small-scale reactionary violence towards police force and as such are unlikely to be destabilising, though the government’s preoccupation with the Boko Haram insurgency and violence against civilians could lead to a mishandling of the south-west regions concerns, threatening to prolong dissent.