The last few months have seen the Islamic State’s Sinai Province carry out a number of attacks on security forces in the Sinai Peninsula, including a raid on an army checkpoint in the Al Barth area that killed at least 23 soldiers (The Guardian, 7 July 2017), and another which targeted a police convoy in the Bir Al-Abd area, killing at least 18 police officers and a driver (CBC, 11 September 2017). These attacks, along with operations that did not make international headlines or provoke government responses, have continued the ongoing low-level insurgency which has plagued the Peninsula since weakening of the central government during the political upheavals of 2011 and 2012.

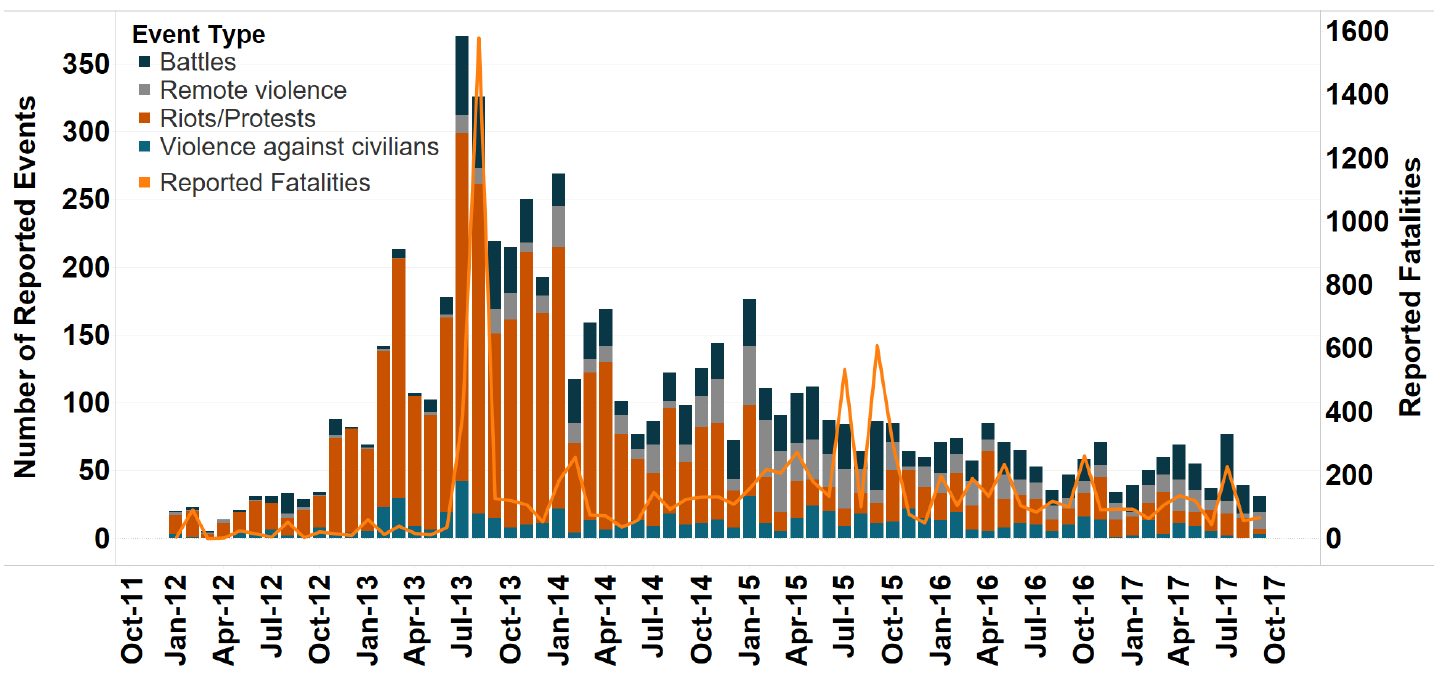

However, when examined from the longer term perspective of the last few years, the ongoing violence in the Sinai actually fits within a trend towards an overall decrease in the number of reported events in Egypt. With around 30 recorded events, September 2017 saw a combined total of conflict events and Riots/Protests at levels comparable to the relative stability witnessed in mid-2012 before the beginning of protests against the government of former President Mohammad Morsi, although still roughly double the average number of recorded events during the period preceding the Egyptian revolution in 2011.

The overall fall in numbers of events in Egypt is due to a fall in all manner of unstable events, and particularly riots and protests. There are a few different reasons for this drop, but the effective dismantling of political freedoms by the state and corresponding contraction of the space for political dissent are an important component, as discussed in our March 2017 article on Egypt (ACLED, March 2017). September 2017 represents a culmination of this trend, demonstrated by the plummeting of riots and protests recorded (see Figure 1).

However, while events in Egypt as a whole have been falling when viewed over the long-term, two inter-connected factors complicate any attempts to draw conclusions from this trend. The first is the Egyptian government’s use of the counter-insurgency campaign in the Sinai Peninsula to justify the continued need for a strong government and consequently the suppression of dissent. The second factor, which is arguably an extension of the first, is the ongoing communications blackout (Washington Post, 15 September 2017) affecting significant parts of the Sinai Peninsula, including its major cities such as Arish, Rafah, and Sheikh Zuweid (Madamsar, 20 September 2017). When combined, these factors suggest that the perception of what is going on in the Sinai is likely distorted by the government. Despite this, the overall trend towards fewer events, if not reduced fatalities, indicates a general return of stability to Egypt over the near term, but is not a positive direction for political freedoms.