Riots and protests reached their highest levels for over two years in September as demonstrators protested the rule of President Faure Gnassingbé. Despite comparatively fewer protests to other countries in Africa, the scale of participation has been large with as many as 800,000 people demonstrating on 19 August (BBC News, 21 September 2017), though the true figure is likely to be lower. The capital, Lomé, has seen the highest level of protest activity since 2013 but it is the activity outside of the centre where developments are taking place.

The protests echo other reform-led protests that have swept the continent since the 1990s, though the thin veneer of promised change from the government has in the short term failed to convince the opposition. The opposition rejected a parliamentary vote to amend the constitution to limit presidential terms to two-terms (BBC News, 21 September 2017), demonstrating that governance reforms that pay lip service to democratic promotion will not prevent street demonstrations from taking place. This pattern is particularly prominent in West Africa where prominent pro-democracy protests took place in Gambia in the run up to President Yahya Jammeh’s electoral defeat.

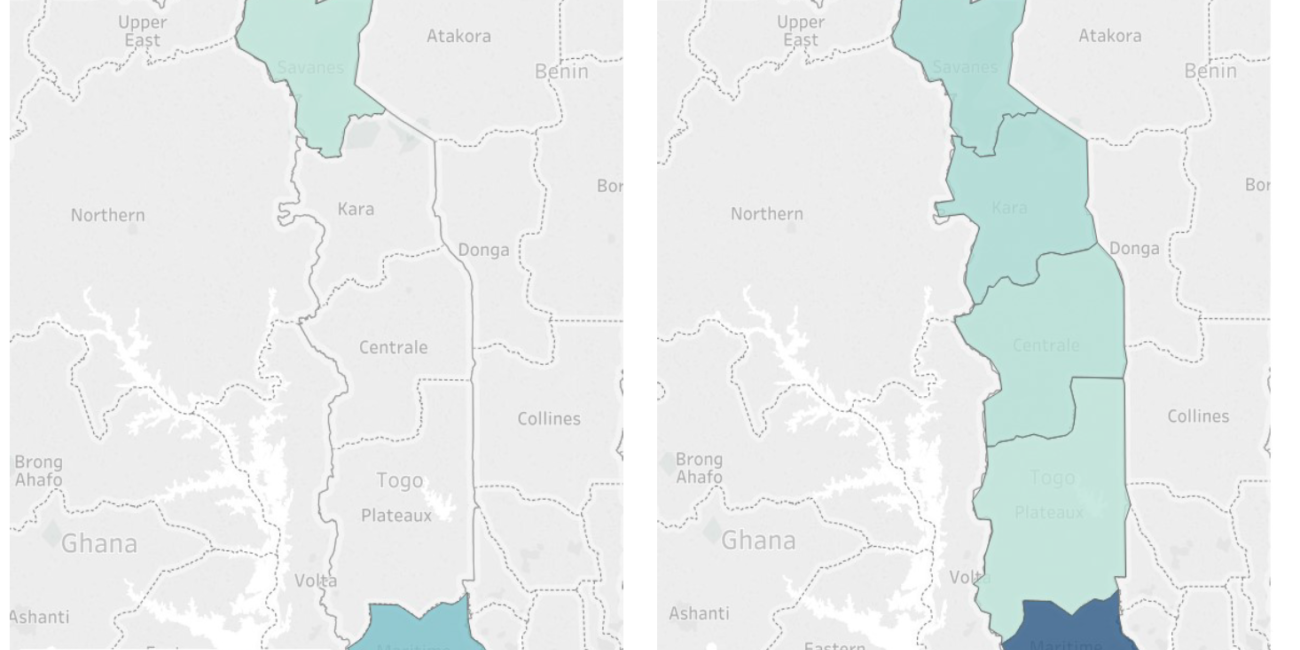

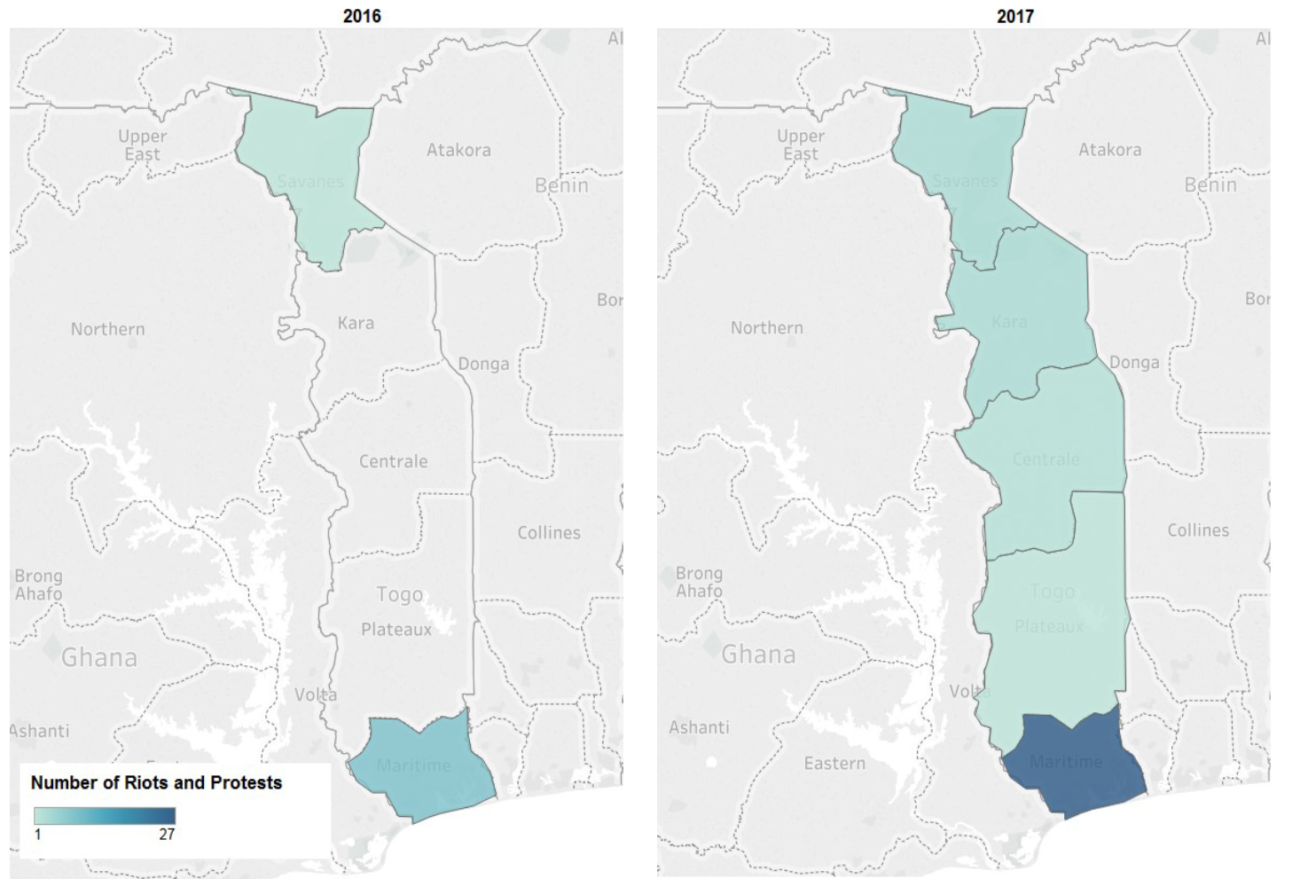

August was comparatively more violent than September with reports of clashes between police forces and rioters supporting the opposition Pan African National Party (PNP). Since June, protests have spread north from Maritime Region to Sokodé in Centrale, Bafilo in Kara and Mango in Savanes Region (see Figure 1). The north has traditionally been a stronghold for the Gnassingbe family.

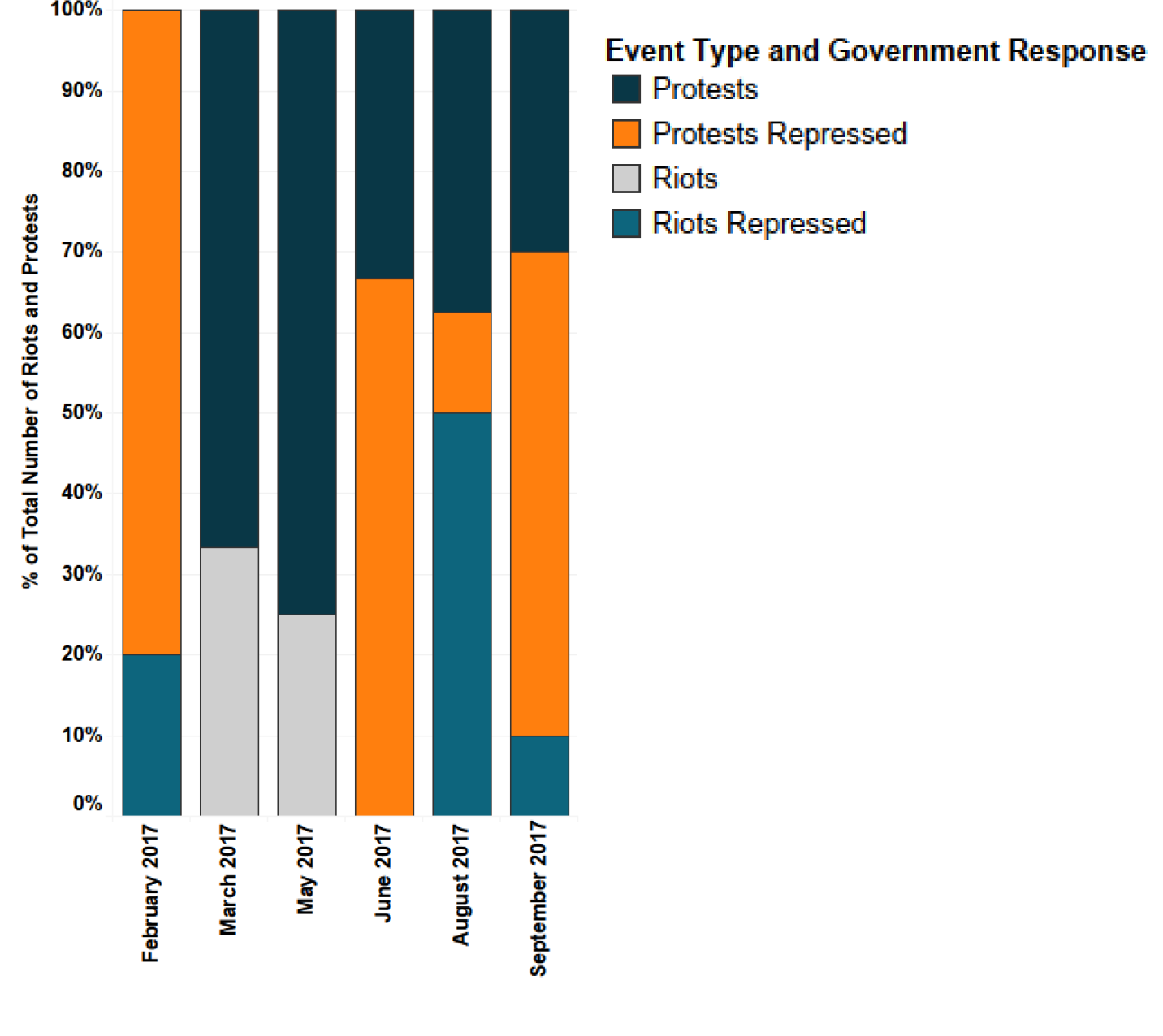

Two potential dynamics present themselves in the Togo protest wave: continuity and incremental alliance building for change. First, the role of the military will be important in determining whether protesters continue to rally. In August and September, 62.5% and 70% of protests were repressed by security forces respectively (see Figure 2). “Military careers were one of the few ways of social advancement for the northern ethnic groups” (Osei, 2016: 14) under Faure’s father – Eyadema.

Key posts in the army are occupied by officers from the Kabye ethnic group and are likely to retain their loyalty rather than capitalise on the political opening of the protest wave, rendering an unexpected ouster less likely.

However, despite lacking representation in the parliament and propelling onto the political scene in 2014, the opposition protest leader has made some shrewd political moves. Tikpi Atchadam – the protest movement leader of the PNP comes from the north of the country and offers the opportunity to bridge the historical divide between the regime-backing north and the opposition south of Togo. Attempts to combine his northern appeal base with Jean-Pierre Fabre, leader of the National Alliance for Change (ANC) that came 2nd in the 2015 Presidential election, could amplify the attractiveness of an alternative political choice to citizens (Le Monde, 7 September 2017) in weeks to come.

While the trend of popular protest is a rising occurrence across North and sub-Saharan Africa, governments appear to be employing similar techniques to insulate themselves from instability. Across the continent, states deploy internet shutdowns, arrange pro-regime protests, and use a mixture of selective concessions and police brutality under differing circumstances and with varying effect. Close attention to the organisation, strategic flexibility, fluid hierarchy of command and closeness to political elites (Tufecki in the New Yorker, 21 August 2017) may well offer important clues as to the true potential of popular protest movements to achieve their goals and/or unseat African leaders.