A number of recent studies explore the relationship between gender inequality and conflict and generally find that higher gender inequality, or lower rates of inclusion, is associated with higher rates of conflict and violence. However, efforts to increase inclusion ought to be accompanied by institutional and normative changes too if negative violent consequences are to be curtailed.

Studies find a link between unbalanced sex ratios (Hudson and den Boer, 2002, 2004), a ‘surplus’ of young men (Hudson et al., 2009), or large youth populations (Urdal, 2008) and a higher likelihood or level of conflict. This vein of literature contends that gender inequality can impact conflict by increasing the capacity to mobilize for conflict, especially through the facilitation of the recruitment of young men (see GIWPS and PRIO, 2017; Forsberg and Olsson, 2016).

A more compelling argument, however, might be that gender inequality can impact conflict and violence through unequal gender norms (see GIWPS and PRIO, 2017; Forsberg and Olsson, 2016) as such norms may legitimize the use of force (Caprioli, 2005; see also: Caprioli 2000, 2003; Caprioli and Boyer, 2001). In this vein, Hudson et al. (2009) point to the role of “patriarchy and its attendant violence,” and reason that, evolutionarily, improved female status can in turn lead to societies where males are “less likely to submit and yield to male coercive violence” (Hudson et al., 2009).

Global indices can be a helpful tool as they distill complex information into a single number: a useful instrument in assessing and comparing multidimensional issues across countries. The new global Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) Index—compiled by the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security (GIWPS), in collaboration with the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)—offers a way to assess gender inequality and development in addition to peace and security. “The index incorporates three basic dimensions of well-being—inclusion (economic, social, political); justice (formal laws and informal discrimination); and security (at the family, community, and societal levels)—and captures and quantifies them through 11 indicators. … [And it finds that] countries are more peaceful and prosperous when women are accorded full and equal rights and opportunity” (GIWPS and PRIO, 2017).

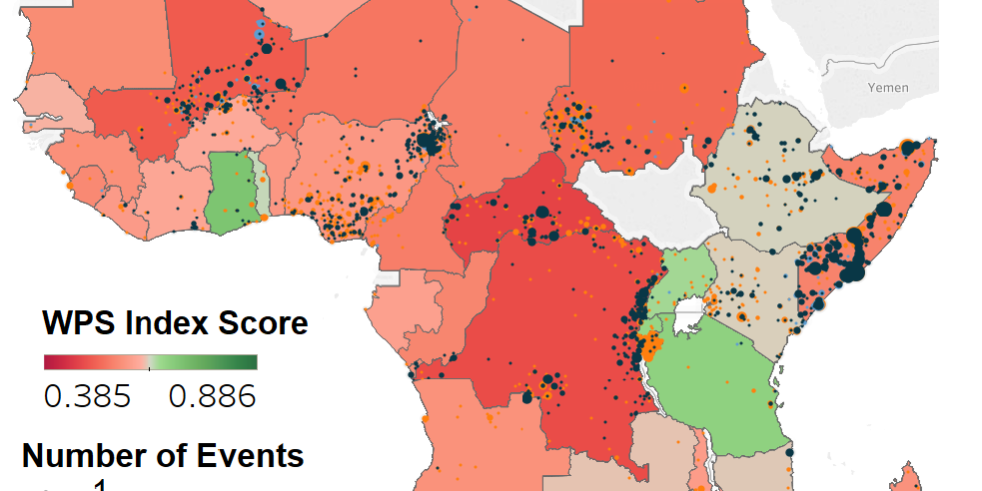

Figure 1 maps the 2017/2018 WPS Index score for African states, overlaid with ACLED political violence data recorded thus far in 2017; Figure 2 depicts the relationship between the WPS Index score and the number of political violence events by country [1]. Indeed, states with a higher WPS Index value, on average, seem to see fewer political violence events than those with a lower WPS Index value [2].

However, ‘inclusion’ alone is not enough. While gains are being made in women’s inclusion where it has long been lacking, this has often been met with a backlash. Berry (2015) notes that as the status of women in many societies grows, they may experience increased violence from men as men attempt to reassert their control through violence (see also: Vyas and Watts, 2008; Ahmed, 2008). A study by the ICRC found that “literate, educated and employed women experienced the highest rates of community violence, suggesting that men use violence as a way of repressing women’s increased status (Rombouts, 2006)” (Berry, 2015).

These trends can in turn point to the rise in political violence women face as opponents seek to discourage their greater participation in the political arena (Kishi, 2017) or their defying of the agendas of powerful male political elites (Berry, Bouka, and Kamuru, 2017). “Women around the world are attacked for being female and involved in politics … by men who wanted to punish or coerce their political choices or prevent them from participating in a political activity like voting or running for office” (Bardall, 2017).

In the recent Kenyan election, for example, more women ran for office than ever before—and they were, in turn, met with targeted and gendered violence (Berry et al., 2017). During the political primaries for the general election, Ann Kanyi, vying for her party’s nomination was dragged from her car and brutally beaten; during the assault, she was asked to quit politics (Wangui, 2017). “Other female candidates were robbed by men armed with machetes and batons (Muhindi, 2017), had their motorcades attacked and supporters killed (Nation, 2017), and were beaten and threatened with public stripping (Kerongo, 2017). … The goal: to turn back progress ushered in by a new gender quota, implemented as part of a 2010 constitutional overhaul, that has vaulted more women into positions of power in Kenya than ever before” (Berry et al., 2017).

In Burundi, during the 2015 political crisis, women were often targeted with sexual and gender-based violence due to their real or suspected party affiliation (or that of family members), lack of support for the president’s third mandate, or suspected participation in the protests against it (Human Rights Watch, 2016). (For more on the Burundi Crisis, see Raleigh, Kishi, and McKnight, 2016). Similar to the Kenyan case, soon before the 2015 political crisis began, Burundi was “one of few countries in the world to have adopted a gender quota for its legislature in an effort to promote the inclusion and participation of women in the political process” (IFES, 2014).

Similar spikes in gendered political violence were seen in Zimbabwe during election periods, where both women running for office as well as those participating in politics at the local-level were targets of violence (Kishi, 2017). Again, similarly, Zimbabwe too included a “special electoral quota system to increase women’s representation in Parliament” in its new constitution, approved in 2013 (UN Women, 2013).

All three of these countries are among the ‘more inclusive’ of African states as they fall within the top half of African states in terms of ranking by the WPS Index.

The establishment of gender quotas aiming to normalize the inclusion of women in politics is necessary. However, it is important that such steps are coupled with efforts to combat gender-based violence and the institutional and normative structures that allow for them. This means both strengthening the rule of law to protect women, while also dismantling the patriarchal structures in place that allow for such behavior as gendered violence (see also: Berry et al., 2017).

[1] Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Libya, and South Sudan are not included in the WPS Index (due to data limitations) and are hence not included in the figures here.

[2] Some degree of correlation is to be expected between the WPS Index and ACLED data, since ‘societal security’ is included in calculation of the index score. However, the WPS Index relies on a measure of conflict-related fatalities from the UCDP dataset, weighted by population, for its ‘societal security’ measure. Hence, looking at specific atomic events here—which include battles, remote violence, and violence against civilians—should be sufficiently different so as to avoid complete correlation here.