In post-civil war Sri Lanka (2009-2018), communal violence erupted along the religious division of the Muslim-Buddhist fault line. The growth of nationalist Sinhalese-Buddhist organizations – such as Bodo Sahitya Sabha (BSS) – combined with a political environment of impunity have led to an increase in the number of attacks on the Muslim minority community (Aljazeera, 13 March 2018).

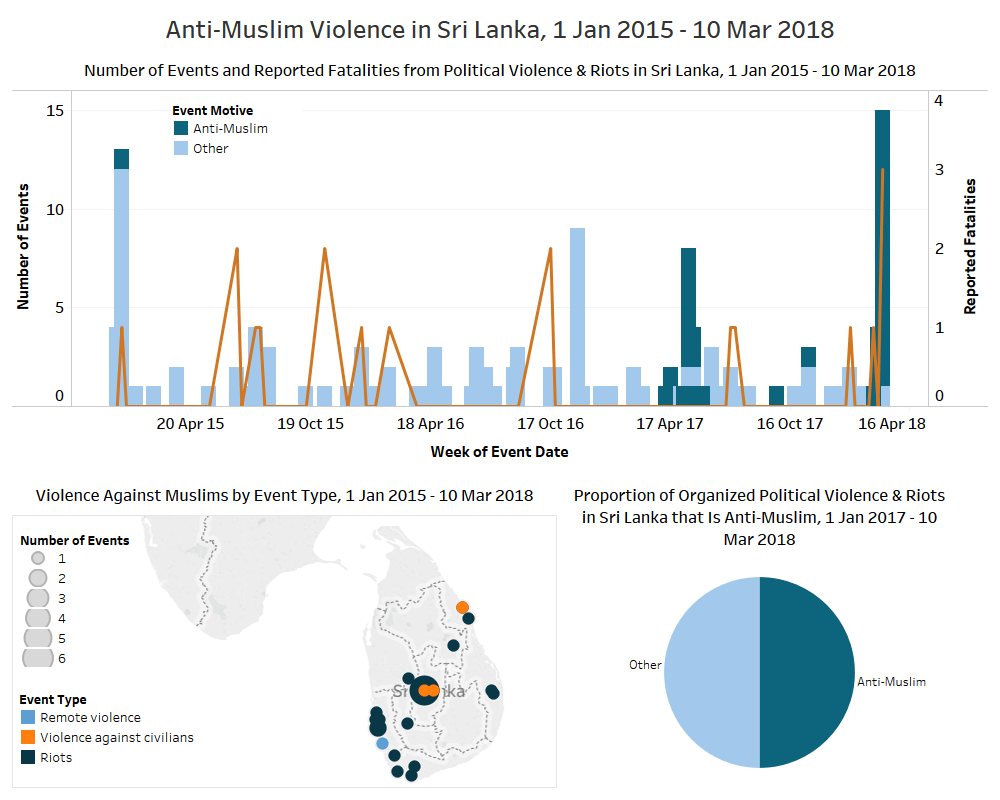

Data from 2015 to 2018 showcase a periodic wave of anti-Muslim violence in Sri Lanka. A number of such incidents have also been reported prior to 2015, with the most significant outbreak of anti-Muslim rioting taking place in June 2014, leaving four people dead (New Straits Times, 14 March 2018). In the two years following the 2014 attack, violence decreased, with only one attack reported in 2015 (see Colombo Page, 8 January 2015). Since April 2017, anti-Muslim sentiments flared up again with 15 events reported throughout 2017. The latest onset of communal violence against Muslims has increased the number of recorded incidents to 18 since the beginning of 2018. The Sri Lankan government has declared a state of emergency for the first time since the end of the civil war to curtail violence in the affected region (CNN, 8 March 2018). The data shows that since January 2017, 50% of all reported incidences of organised violence and riots have been directed against Muslims.

Attacks on the Muslim minority group are typically limited to rioting and arson, and their lethality has been low. Anti-Muslim violence has been predominantly concentrated in the south, east, and center of Sri Lanka, whereas the northern provinces have been less affected. Continued incidents of anti-Muslim violence in the country are indicative of the mainstreaming of hard-line Buddhist nationalism and could make Sri Lanka a tinderbox for future communal violence.