Since the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn on 15 February, followed by the 16 February State of Emergency, political violence in Ethiopia has been marked by two primary trends – a decrease in riots and protests, and an increase in violence against civilians.

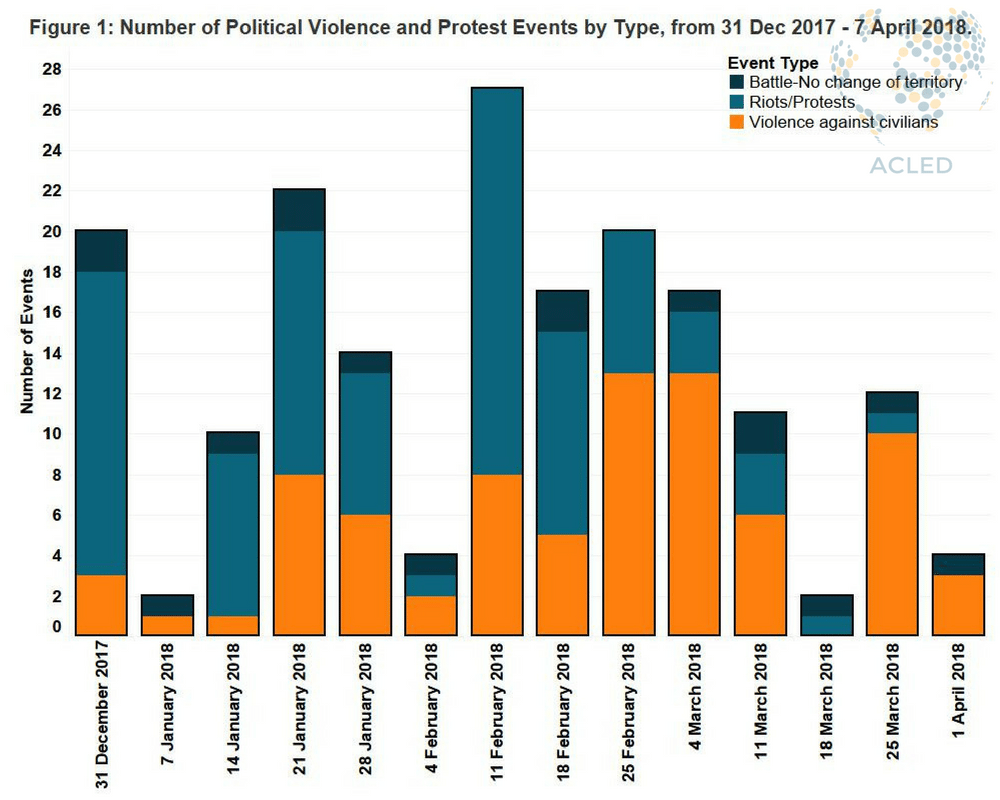

Riots and protests spiked in the week of the resignation (beginning 11 February), but have since dropped dramatically to an average of 3 protests per week between 25 February and 25 March (see Figure 1). Two significant developments explain this drop-off in protests. The first is the State of Emergency and subsequent crackdown on Oromo dissent. Second, the chair of the Oromo People’s Democratic Organisation (OPDO), Abiy Ahmed, was elected as Ethiopian Prime Minister on 2 April. The drop in protests can be partly explained by the positive nationwide response to Ahmed’s election. The government’s efforts to release prisoners who had been held under the State of Emergency is also an attempt to appease tensions. However, the protesters might simply have been limited by the State of Emergency, which effectively bans any protest or any public activity that could incite unrest (BBC, 21 February 2018).

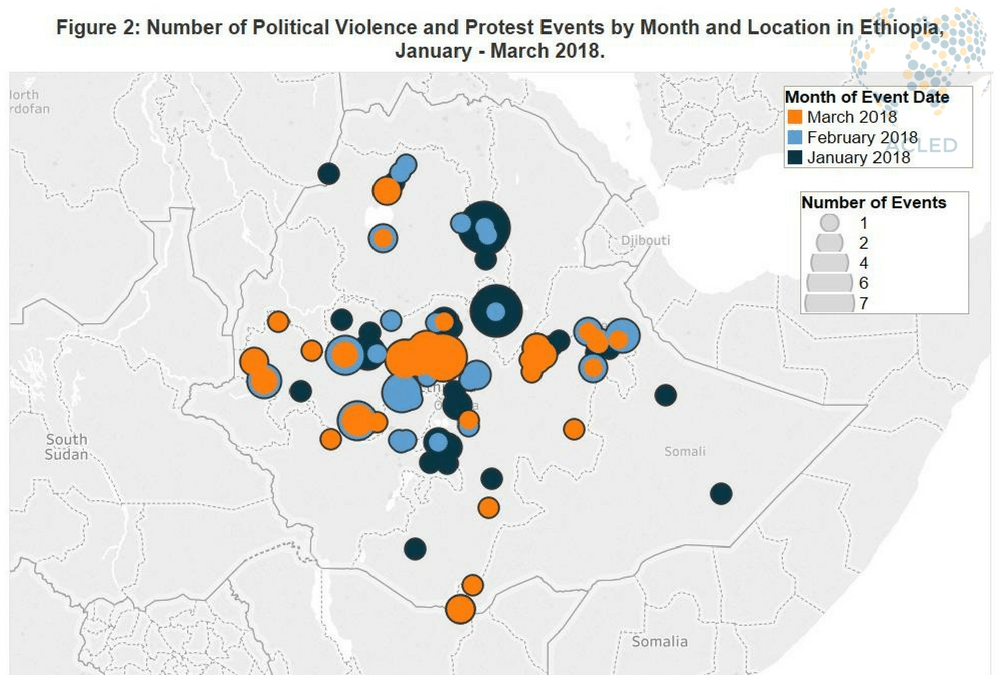

Moreover, in the weeks following the State of Emergency, particularly in March and prior to the inauguration of Desalegn’s replacement, there was a rise in violence against civilians (see Figure 2). Under the State of Emergency, civilian-targeted violence has primarily been carried out by the military and police force.

Another change in the violence profile of Ethiopia is the drop in the presence of the Somali state’s paramilitary force, the Liyu police. In 2017, they were responsible for 23% of violence against civilians, whereas from 1 January to 7 April 2018, they were responsible for only 8% of civilian targeting. This could indicate that Ethiopia’s federal government is no longer enabling regional militia groups to exacerbate tensions along ethnic lines and that the Ethiopian crisis has re-orientated around core political issues and Ethiopian nationalism.

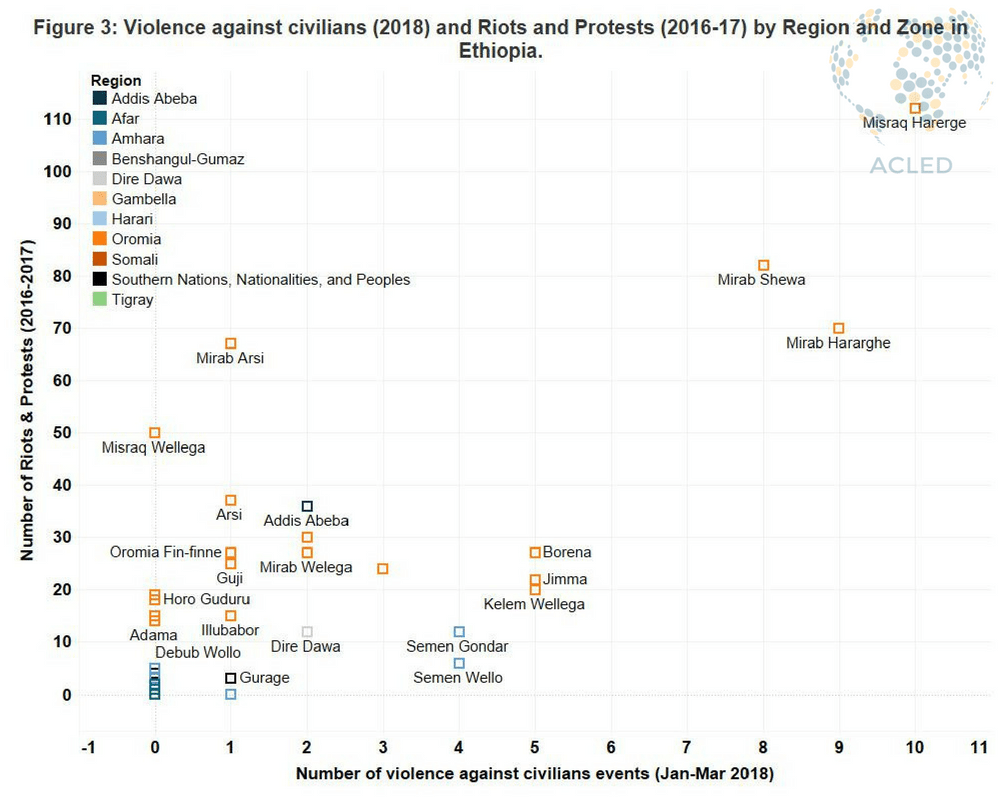

As in 2016 and 2017, political violence remains concentrated in the Oromia region in 2018. Misraq Hararghe, Mirab Hararghe and Mirab Shewa attracted the highest levels of violence against civilians (see top right of Figure 3). Misraq Hararghe and Mirab Hararghe also experienced the highest levels of organised violence in 2016 and 2017, as there were a number of clashes between the Oromo Liberation Front and Ethiopian security forces, or between Oromo militias and Somali militias and Liyu police. Until now, the Ethiopian government has pursued a strategy of deterrence, which targets areas it deems most susceptible to re-occurrences of organised violence. However, the inauguration of the country’s first Oromo Prime Minister (The Star, 9 April 2018), should precipitate both a reduction in clashes and violence against civilians in the Oromo region.