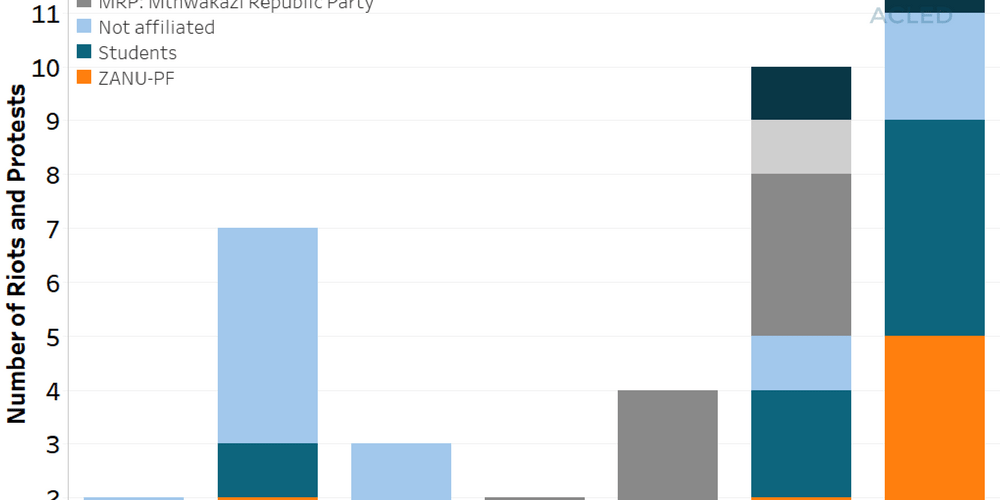

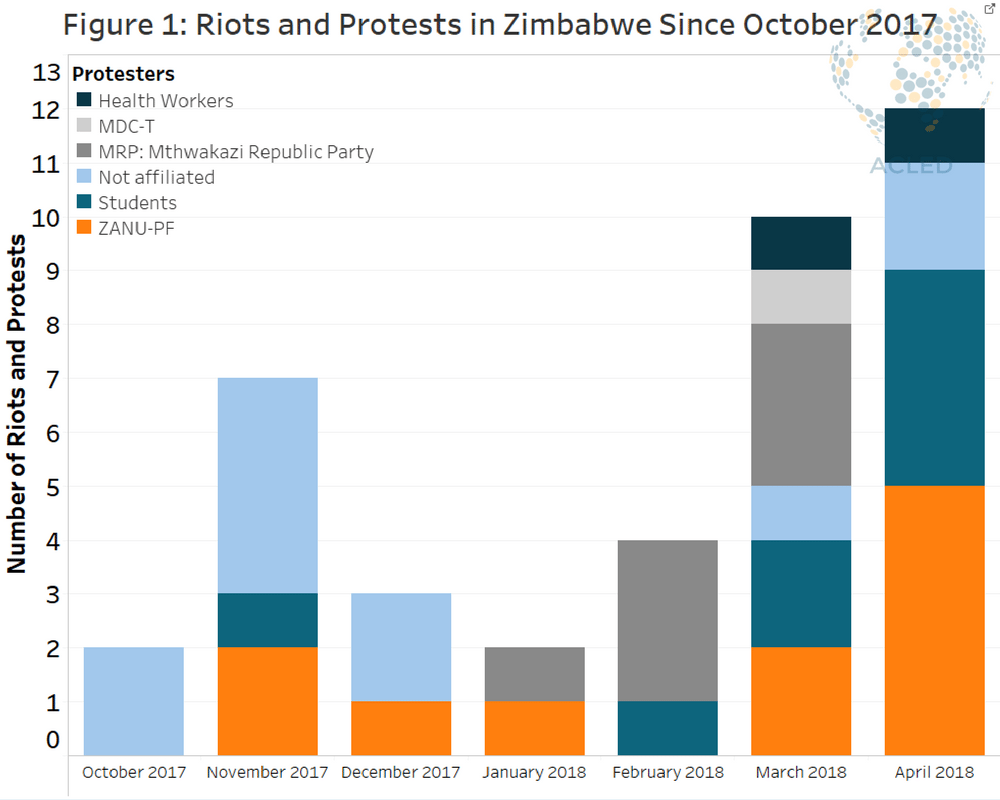

On 17 April, the Zimbabwean government drew international attention and outrage when it responded to a nurses’ strike by firing a third of the public health sector nurses (VOA, 24 April 2018). This nurses’ strike is not an isolated incident; it is a reflection of the increasing unrest and dissatisfaction since the coup in November 2017. Figure 1 shows the incidents of riots and protest since October 2017 – a spike in November reflects the protests that accompanied the military take-over of the government; levels of protest fall in December, January and February, reflecting the relative goodwill for the new government. However, in March, protest activity doubled, and by the third week of April more protests occurred.

The majority of protests are not opposition-coordinated, nor are they aimed directly at the new government. The grievances are economic and social factors; students protest increased fees (Newsday, 17 April), and doctors, teachers and nurses protest low salaries. Since the inauguration of President Mnangagwa, the government has failed to resolve the cash shortage or reverse the shrinking of the economy (Bulawayo24, 3 April 2018). The growing economic anxiety is reflected in the increasing protest levels, which belie the image of stability and economic progress projected to international investors by Mnangagwa’s government.

The other important actors are ZANU-PF supporters. There has been an increase in protest (and rioting) by local ZANU-PF structures. These spiked during the run-up to the party primaries on 29 April (The Herald, 23 April 2018), as local-level supporters tried to block candidates imposed by senior national politicians. These local-level protests taking place in rural towns confute the image of party unity and popularity projected by ZANU PF’s #EDhasmyvote election campaign. Despite these actions, there is little doubt–at present–that the current government will face any serious opposition (internally or externally) in the election.