On 27 January 2018, the Jordanian government approved a new budget which removed subsidies on wheat and imposed a tax hike on over 100 common items. However, protests in the kingdom were less attended and less widespread than anticipated due to the same factors that limited protests during the Arab Spring.

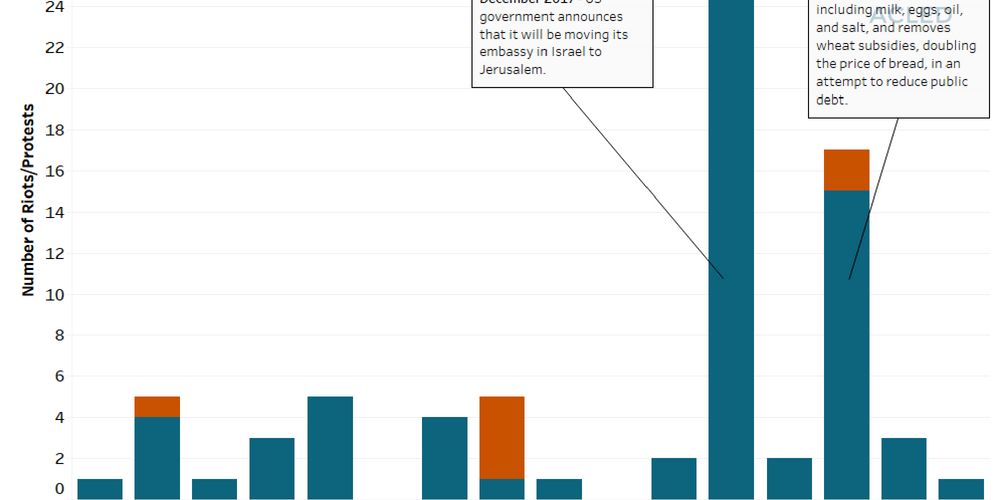

During the Arab Spring, protests in Jordan were limited by internal divisions, the middle class economy, and concerns of political consequences (MEPC, 14 March 2012). Jordan has a complex ethnic demography with the majority of the country’s inhabitants being non-Jordanians. Even within the so-called ‘true Jordanian’ population there are tribal conflicts negatively impacting cohesion. There is more cohesion within economic classes in Jordan, particularly the middle class which according to Tobin has become its own imagined community emanating from Amman (MEPC, 14 March 2012). However, the middle class in Jordan tends to be politically informed but not politically active and, if involved in protest, seeks reform over revolution, as was seen in 2011 and 2012. Finally, in Jordan there is real fear of political consequence from protesting. People fear being arrested or imprisoned for activism. Additionally, witnessing events in Iraq, Egypt, and most importantly Syria, has made many more cautious about attending protests. These factors all limit the development of widespread protests. The fact that demonstrations in Jordan are sparse hence makes the two significant spikes in riots and protests in the country over the last 6 months more significant (see Figure 1).

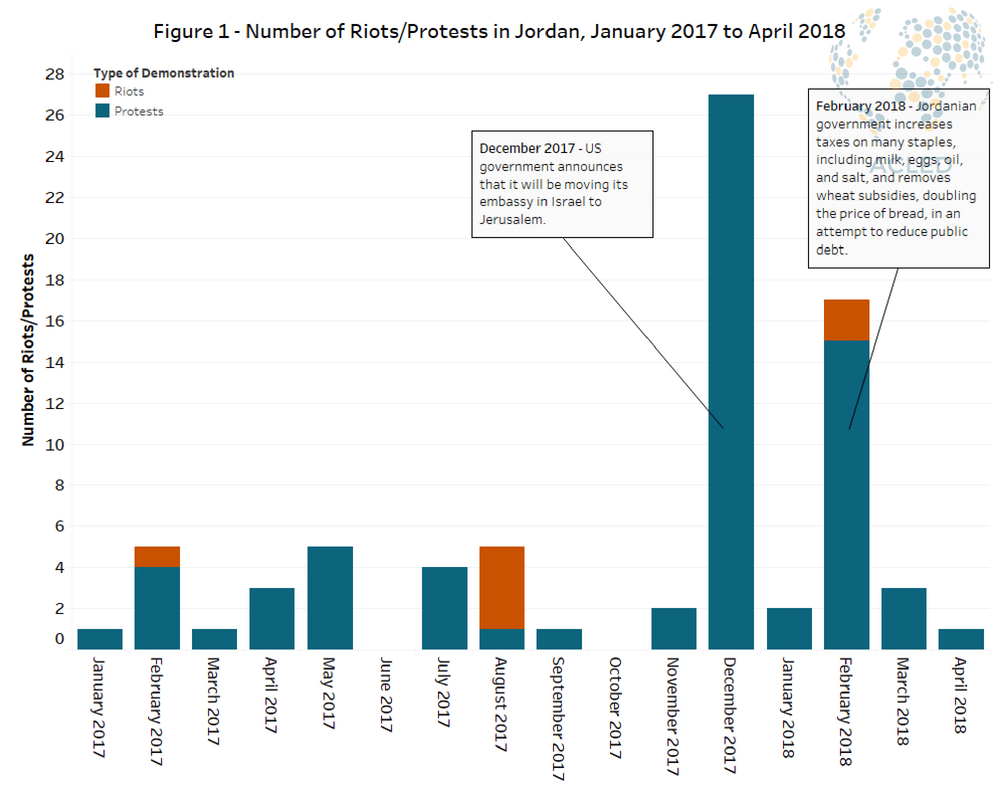

The first spike in demonstrations was in December 2017, where the number of demonstrations in the country rose sharply following the US government’s announcement that it would be moving its embassy to Jerusalem. This announcement resulted in widespread demonstrations around much of the Middle East and North Africa (for example, see ACLED 2018). Interestingly, support for Palestine was not limited in the way protests tend to be in Jordan. Support for Palestine is strong in Jordan across internal divisions. In Jordan, there are more than 2 million registered Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) and more than half of the population of Jordan has Palestinian ancestry (Human Rights Watch, 1 Feb 2010). Additionally, the Jordanian royal family has custodianship over Muslim and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem and the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf, which maintains the Temple, is supported by Jordan. These factors in addition to the religious significance of Jerusalem, contribute to the importance of the Palestinian national case in Jordan and the clear ability for Jerusalem to catalyze Jordanian protest movements.

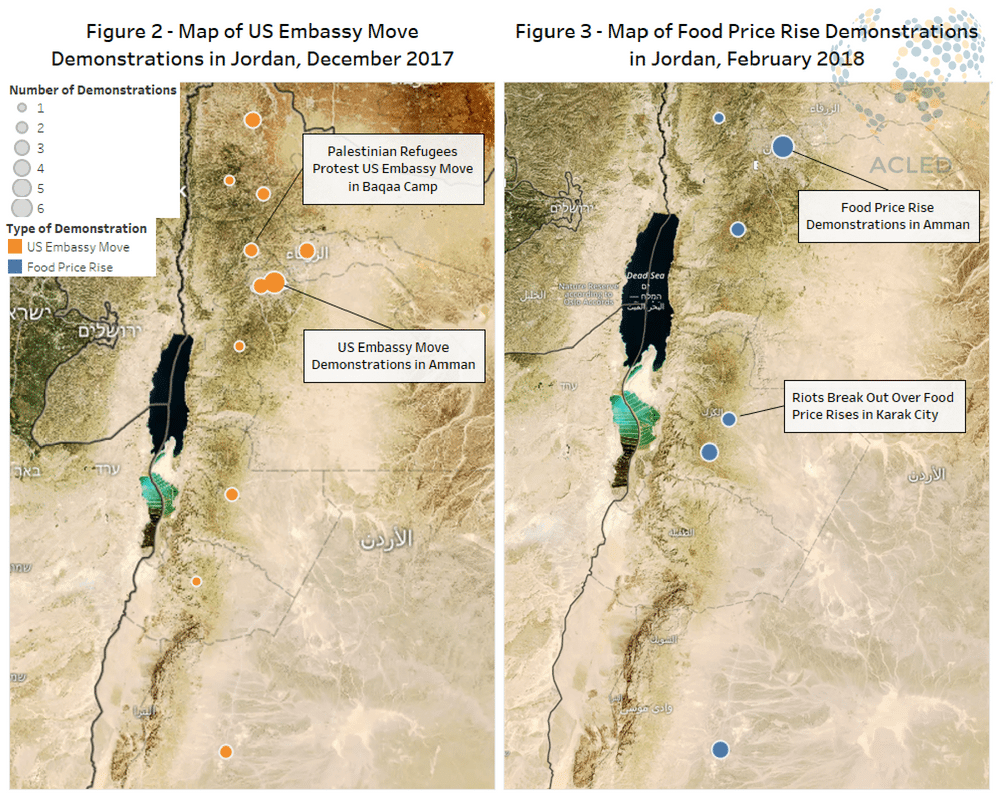

The second spike in demonstrations was in February 2018 (see Figure 1), following the Jordanian government’s decision to remove subsidies and impose tax increases on hundreds of items. In an effort to address Jordanian debt, the Jordanian government increased taxes on hundreds of goods including vegetables, milk, oil, and salt and just over a week later removed subsidies on wheat — doubling the price of bread (Al-Monitor, 23 March 2018). With a third of the population living below the poverty line and unemployment at 18%, these changes are expected to significantly impact the Jordanian population (Al Monitor, 20 February 2018). The most active group in the protests against the rising taxes have been Jordanian farmers who have been negatively affected by decreasing exports due to the war in Syria (The Economist, 28 April 2018).

While the Jerusalem-related protests of December 2017 were more widespread than those in February 2018, they were still concentrated in urban areas, including refugee camps. Meanwhile, the February protests were not as large or widespread as anticipated due to the same factors that limited protest activity during the Arab Spring (The National, 5 Feb 2018; Al Monitor, 20 Feb 2018); these demonstrations were concentrated in agricultural and tribal areas, and despite the extensive impact of the new government budget, protest turnout was low (see Figures 2 and 3).

Protest movements in Jordan related to domestic issues are still subject to the same limiting factors that were present during the Arab Spring — which makes protests in solidarity with Palestine unique as they seem to not be subject to all of those same limiting factors. This, in conjunction with the high numbers of Palestinian refugees in Jordan and their centralization in urban areas, points to why there were more protests in December against the US embassy move to Jerusalem than in February against domestic tax increases.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskHuman RightsMiddle EastPolitical StabilityResourcesRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians