Since the beginning of May 2018, voters in both Lebanon and Iraq have gone to the polls in historic elections. There have been concerns that these elections could spark violence amongst the participating actors due to sectarian tensions and the divisive political landscapes in these countries — as well as pressures from the Syrian Civil War and conflict with the Islamic State (IS). However, a relatively low amount of organized, election-related political violence was reported in both cases involving actors participating in these elections – suggesting a general consensus among these actors that adherence to the existing political systems is the right path forward in these countries.

In Iraq’s case, this was the country’s first parliamentary election since the government formally declared victory against the IS in December 2017 (New York Times, December 9, 2017). The elections took place within the context of the failed Kurdish independence bid last year and concerns from Sunni parties over the fairness of the election given that many internally displaced people (IDPs) and refugees from Iraq’s Sunni areas – which, until recently, were under IS control – have yet to return to their homes. These dynamics created tensions within the country in the run-up to the election on May 12 (Middle East Eye, February 5, 2018).

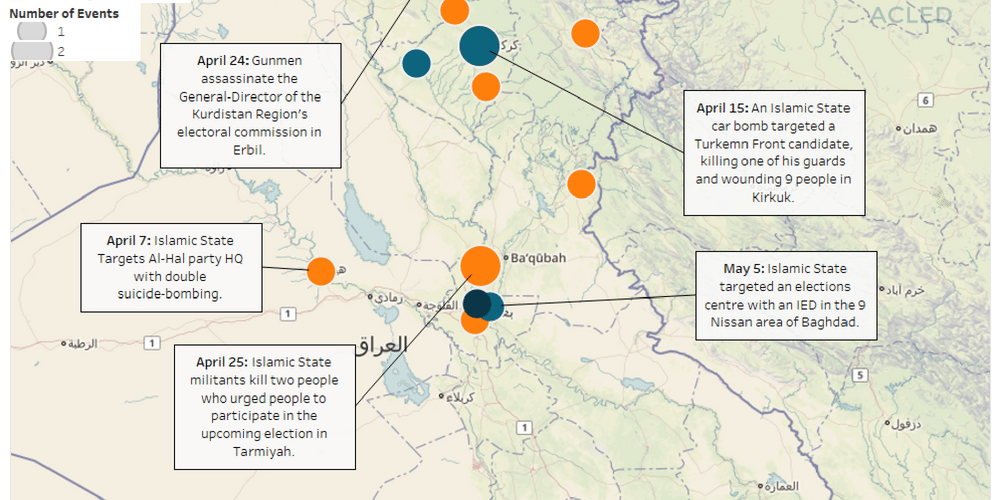

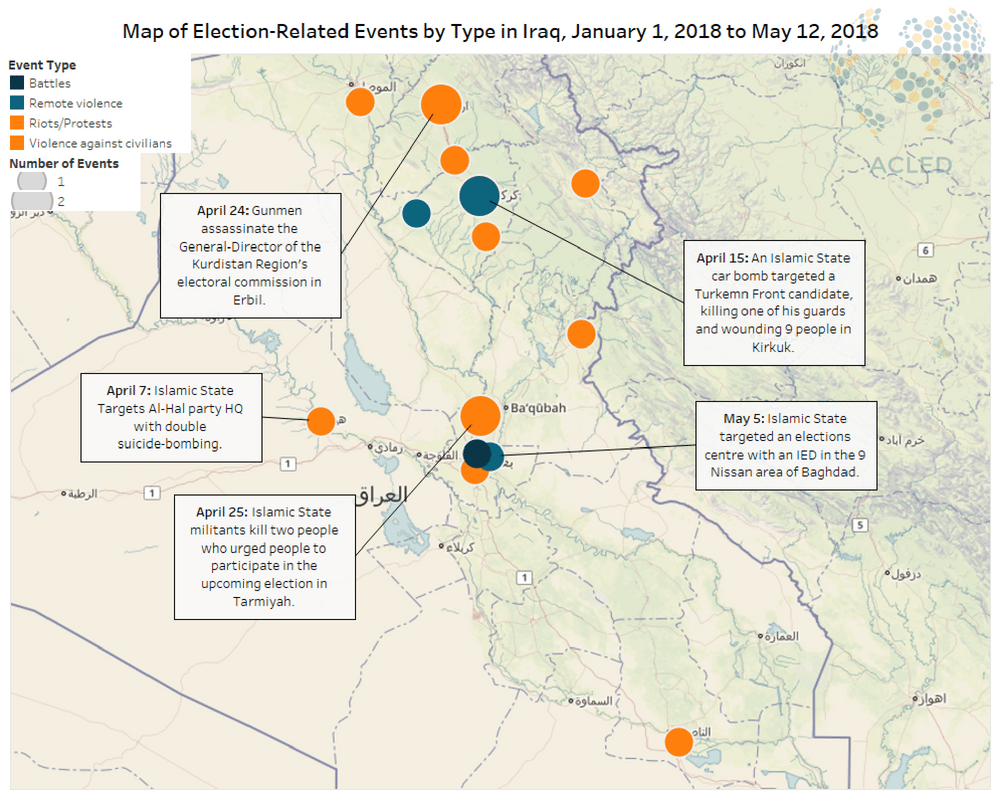

And it was within this tense context that IS stated, in an audio message that was released on April 22, that anyone who ran or attempted to vote in the May 12 election would be targeted by the group (Reuters, April 28, 2018). Following this recording, the number of attacks against candidates, electoral officials, and citizens preparing to vote all rose gradually, with a particular escalation in attacks against electoral candidates in the two weeks before the election (Education for Peace in Iraq Center, May 10, 2018). The map below depicts the location of these events and the circumstances around a few of the most notable ones. These attacks were reported primarily in the northern governorates of Iraq, including in Anbar, Baghdad, Diyala, Kirkuk, Ninewa, and Sala al-Din. While a number of them were claimed by IS, the perpetrators of many others remain unknown.

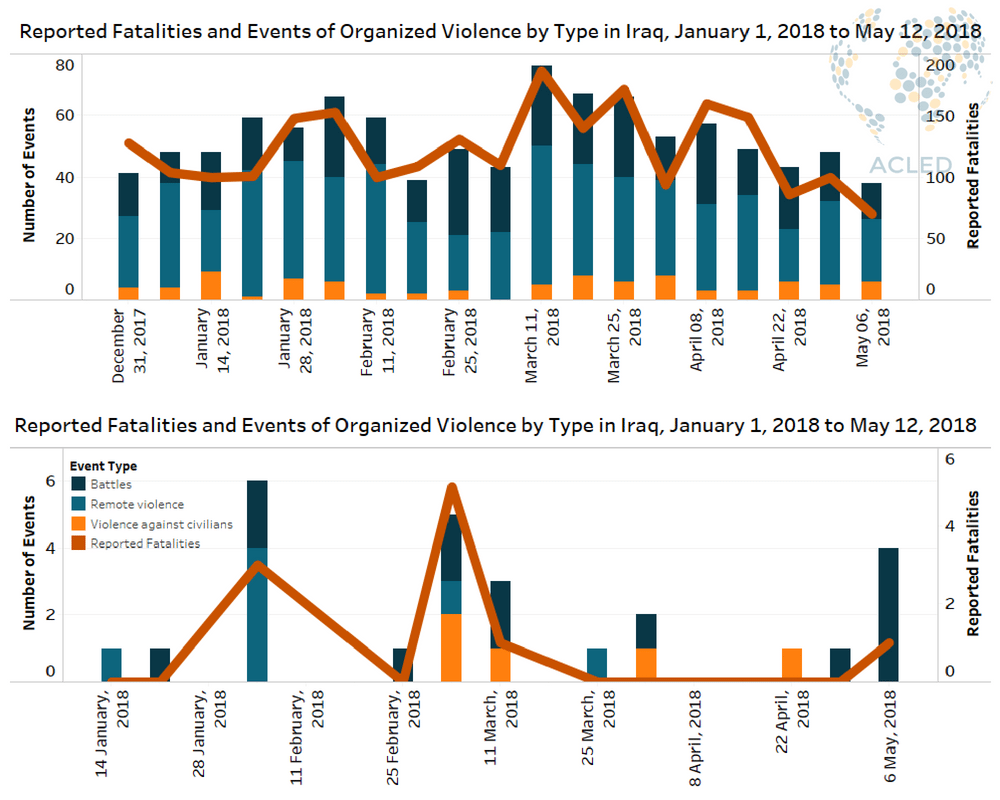

When examined in the broader context of Iraqi political violence however, these events have occurred within an overall drop in both the number of reported events as well as fatalities in Iraq (see graph below). Additionally, no significant post-election violence has yet been reported in Iraq. This suggests on the one hand that the Islamic State’s operational capacity in Iraq has been significantly diminished compared to this same time last year when it still held significant territory, while on the other that the parties to the election are largely committed to the democratic process, despite existing tensions, given their reportedly peaceful participation in the election.

In Lebanon, meanwhile, the parliamentary election held on May 6 was the first to be held in the country in nine years. These elections were originally planned for 2013, but were postponed due to the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War, which has resulted in considerable spillover violence in Lebanon as well as a massive expansion in the country’s refugee population (for more on Syrian spillover violence in Lebanon, see this recent ACLED infographic). Lebanon’s May 6 election is also the first since the passage of the country’s new electoral law adopted in 2017 to address sectarianism by instituting a proportional representation system. By reforming the system, the intent was to open more opportunity for independent candidates to earn a seat in parliament (29 June 2017, The New Yorker). This was deemed necessary due to the tense relations that exist within Lebanon’s population, particularly between its large populations of Shiites, Sunnis, and Maronite Christians, as well as smaller groups such as the Druze and Orthodox Christians (Berkeley Centre, August 2013).

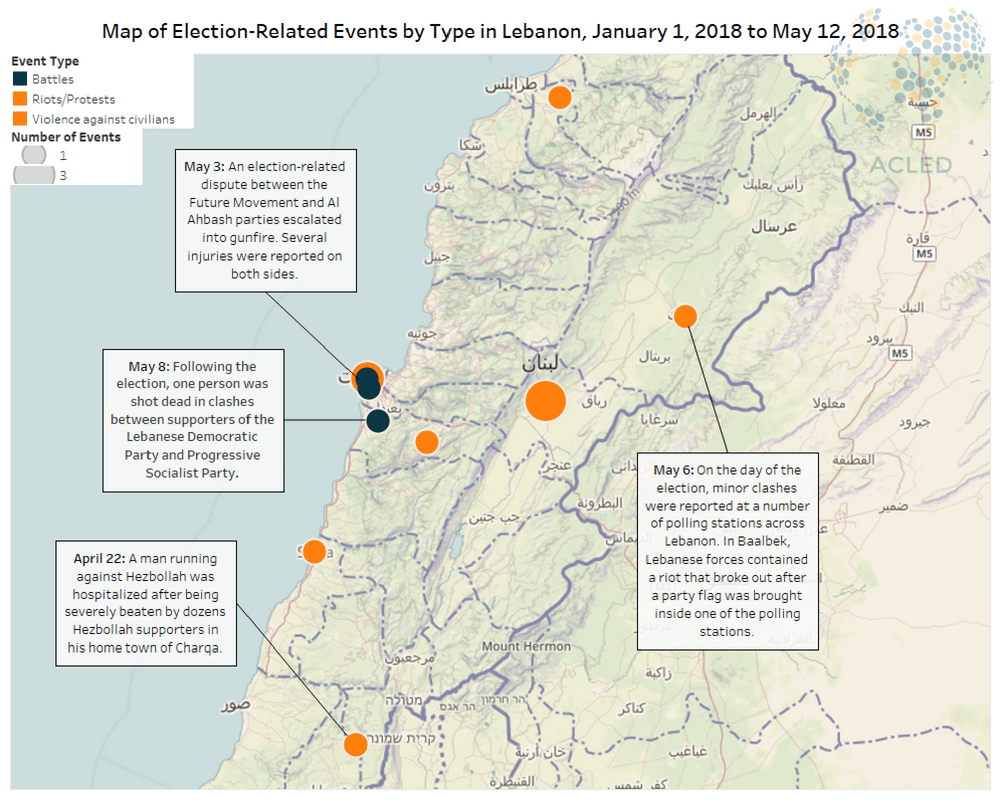

While there were a number of clashes in Lebanon between partisan groups in the run-up to the elections and on the day of the vote, those involved were largely unarmed and no fatalities were reported — although one person was reportedly killed in a clash that broke out a couple days after the election. The map below depicts the location of these events and the circumstances around a few of the most notable.

Given that Lebanon is one of the most diverse countries in the Middle East and is still overcoming the political and social obstacles created by its 15-year civil war (The New Yorker, June 29, 2018), the relatively low-level of election-related violence surrounding this election can be considered a significant success for Lebanon’s electoral system. This is especially true given that, outside of isolated incidents — like the clash mentioned above, which resulted in the only reported election-related fatality — there has also yet to be any widespread unrest related to the results of the election.

In both of these countries, the potential for considerable election-related violence existed due to long-standing sectarian tensions along religious, ethnic, and political axes (e.g. Shia-Sunni, Christian-Muslim, Arab-Kurd), which have in the past been major fault lines in these countries (Carnegie Middle East Center, June 30, 2017). However, it appears that after many years of tensions and considerable pressure placed on these countries via their direct or indirect roles in regional conflicts, the governments and populations of Iraq and Lebanon are placing a greater focus on stability (New York Times, May 13, 2018; The Daily Star, May 11, 2018). One notable way this can be seen is in the lack of any overt violence carried out by groups participating in the political process. And despite attempts by IS militants to violently suppress the vote in Iraq, there were no reports of actors participating in the democratic process in either country attempting to engage in such violence. This suggests a general consensus among political actors in these countries that adherence to the existing political system is the right path forward.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskElectionsMiddle EastPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians