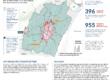

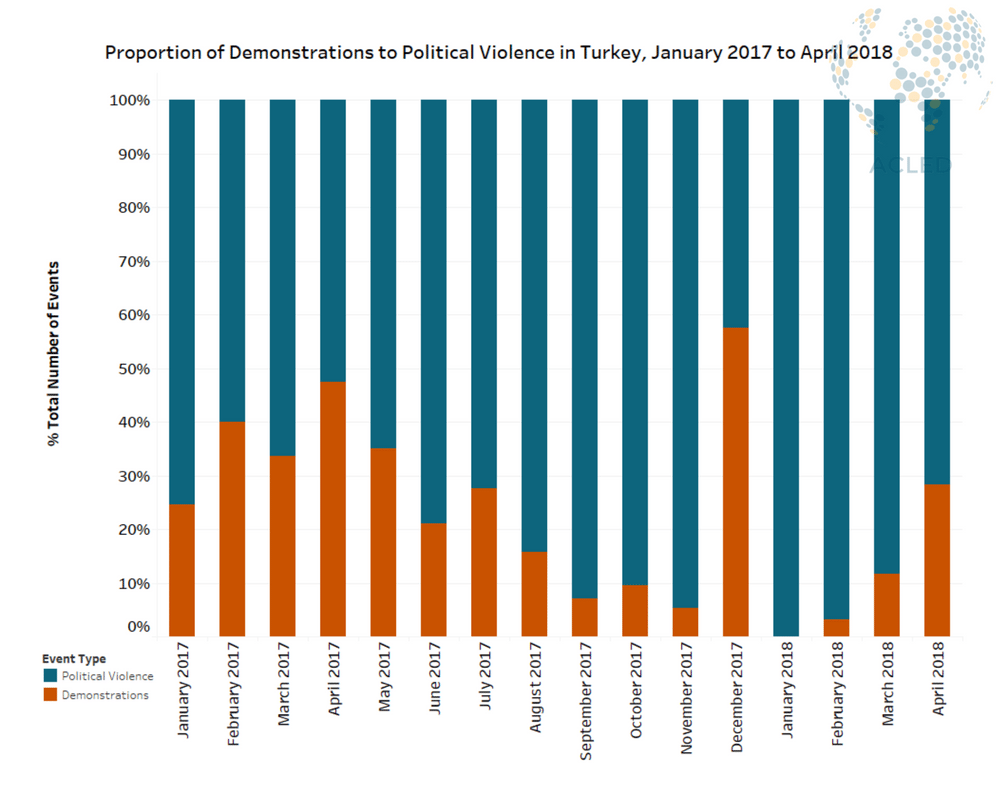

On April 16 of last year, the people of Turkey voted in favor of a constitutional referendum approving a series of amendments which significantly expanded the powers of the presidency, held by Justice and Development Party (AKP) leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The referendum resulted in an extremely narrow victory at 51% for and 49% against, which was sustained despite claims of irregularities in the voting process and calls by the opposition to annul the results. Since then, political violence has risen in Turkey considerably relative to demonstrations (see graph below), suggesting a move away from allowing dissenting opinions to be heard and towards increased stability through pursuit of greater security.

This broad trend towards a relative rise in political violence and a relative decrease in demonstrations can be seen as a result of the Turkish government’s crackdown on dissenting opinions following the referendum (The Guardian, July 14, 2017) and pursuit of greater stability through use of the military (Centre for Security Studies, February 2018). This is further illustrated through Turkey’s interventions in both Syria (for more, see this recent ACLED piece) and Iraq (for more, see this recent ACLED piece) following the referendum. These initiatives have allowed the Turkish government and President Erdogan to double down on showing strength through military action (Foreign Policy, February 7, 2018), particularly in terms of their ongoing conflicts with Kurdish militant groups and the Islamic State.

Looking forward, it seems likely that President Erdogan’s government will continue to prioritize stability while cracking down on dissent (Amnesty International, April 26, 2018), resulting in low numbers of demonstrations and high-levels of political violence as Turkish security forces engage with militants groups both inside and outside of Turkey. Demonstrations that align with the government’s worldview — such as those against the move of the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem witnessed over the past week (see this link for more on this) — can be expected to continue, while demonstrations by opposition groups, civil society activists, and journalists will likely continue to face repression.