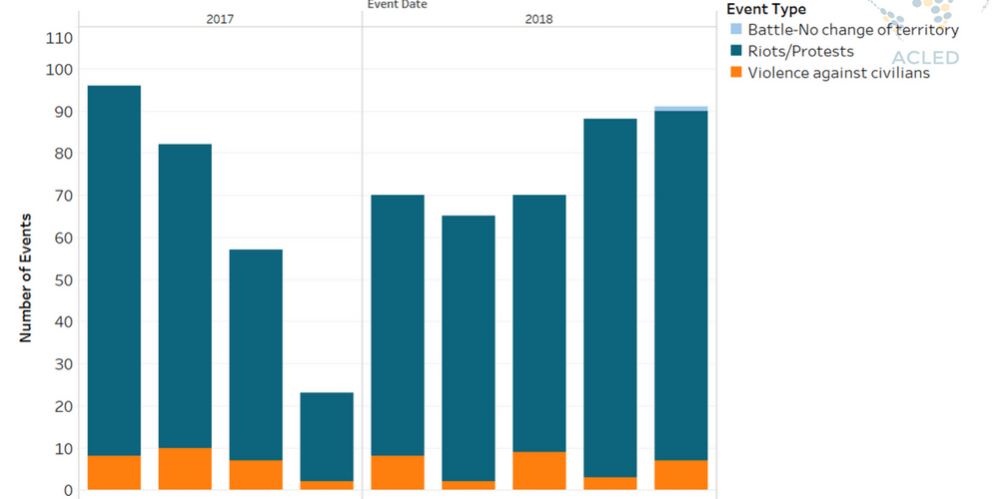

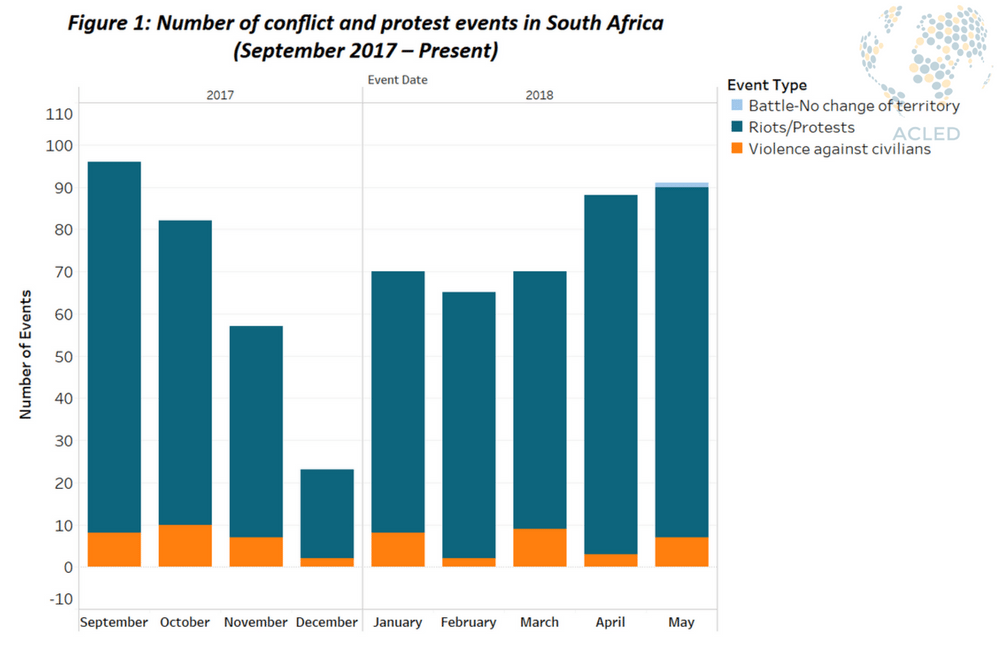

2018 has seen modest levels of political violence and protest events in South Africa relative to preceding years. The decrease in events can be explained by a number of factors, including the absence of elections (election violence), the decrease in student protests at tertiary institutions nationwide and the February 2018 change in leadership from the controversial Jacob Zuma to Cyril Ramaphosa. In recent months however, South Africa has seen a sharp rise in protest and riot events, matching levels not seen since September 2017 (See Figure 1). This rise has been particularly pronounced in April and May 2018, as protesters have taken to the streets over inefficient government services, including the allocation of housing and land.

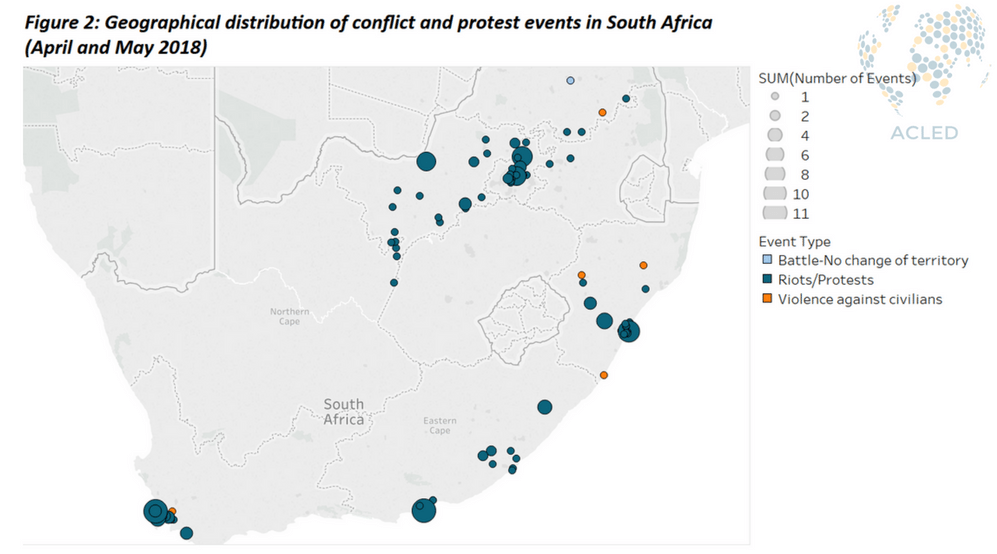

In April 2018, protests and riots erupted in towns and cities throughout the North-West province (see Figure 2). The perceived lack of governance in the province, as well as corruption on the part of the province’s Premier, Supra Mahumapelo, led to residents taking to the streets demanding his resignation. Indeed, events in the province escalated to the point where newly instated President Ramaphosa was compelled to return from a state trip to the United Kingdom in attempts to remedy the situation. The province has, for years, been plagued by inefficient management of government resources and inadequate service delivery. The fact that every audit from each of the province’s constituencies for the past five years has reported high levels of corruption speaks to this issue. Indeed, out of all the country’s provinces, the North-West has the lowest number of clean audits. Under heavy political pressure, Mahumapelo eventually resigned from the provincial government, and the North-West was put under the administration of the central government.

The disorder that plagued the North-West in recent weeks speaks to the larger problem of inadequate service delivery throughout the country. While issues such as sanitation, affordable transport, education and electricity often spark protest action, the issues of housing and land have been particularly dominant recently. Constitutionally, South Africans are guaranteed access to adequate housing, and although government has built upwards of 4 million low-cost houses in the post-Apartheid era, the government has been unable to handle the burgeoning demand, especially in urban centers. Mimicking global trends, increasing numbers of South Africans are gravitating towards to urban areas in search of better prospects. Such urban migration puts pressure on an already stressed government fiscus, and evidence suggests that local governments, even if they are run efficiently, are unable to meet the rising demand. Indeed, the City of Cape Town, a municipality which has consistently received clean audits, has a housing backlog of 575 000. Such housing backlogs prompt the homeless and landless populations to occupy vacant urban land, often resulting in municipal demolition teams tearing down these informal and illegal settlements, which often leads to backlashes and riots from these populations. Recent protests in April and May 2018, centered in peri-urban spaces such as Vrygrond, Parktown and Phillipi in Cape Town and Protea Glen and Eldorado Park in Johannesburg, are primary examples of this ever-increasing phenomenon in South Africa.

At the African National Congress Elective Conference in December 2017, now-President Ramaphosa expressed the urgent need to address the land issues in South Africa. While his rise to power in February 2018 has given South Africans hope for a brighter future, basic services, such as access to housing and land, if not adequately dealt with, will result in more violent protests in the forgotten backwaters of urban South Africa.

AfricaAnalysisCivilians At RiskElectionsPolitical StabilityResourcesRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians