Iran has been the stage of a new wave of civil unrest since the final days of December 2017, when citizens gathered in the streets in demonstrations that turned deadly (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece). Thousands amassed in these gatherings to air general popular grievances, mostly related to the country’s economic situation. Both before and after the two-week period of mass civil unrest at the beginning of 2018, labour groups and economic grievances have been the primary driver of the civil unrest that continues to rock Iran. However, besides the regime’s poor addressal of these issues, several other factors have led to the sustainment of higher levels of civil unrest in 2018 than was seen in the previous year, even after the fizzling out of the mass mobilization on display around the beginning of 2018. Among these factors is the momentum from the aforementioned spike in demonstrations, increasing US rhetoric against the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) (Arms Control Association, 6 June 2018), and the perceived effects of Iran’s involvement in regional conflicts on domestic welfare. The regime’s inability, or unwillingness, to properly address the nation’s economic problems–including mass layoffs, unpaid salaries, and the mistreatment of striking workers by employers and police forces–as well as the then-potential withdrawal of the US from JCPOA, have raised tensions as Iranians fear the possibility that their already troubled livelihoods could become even worse.

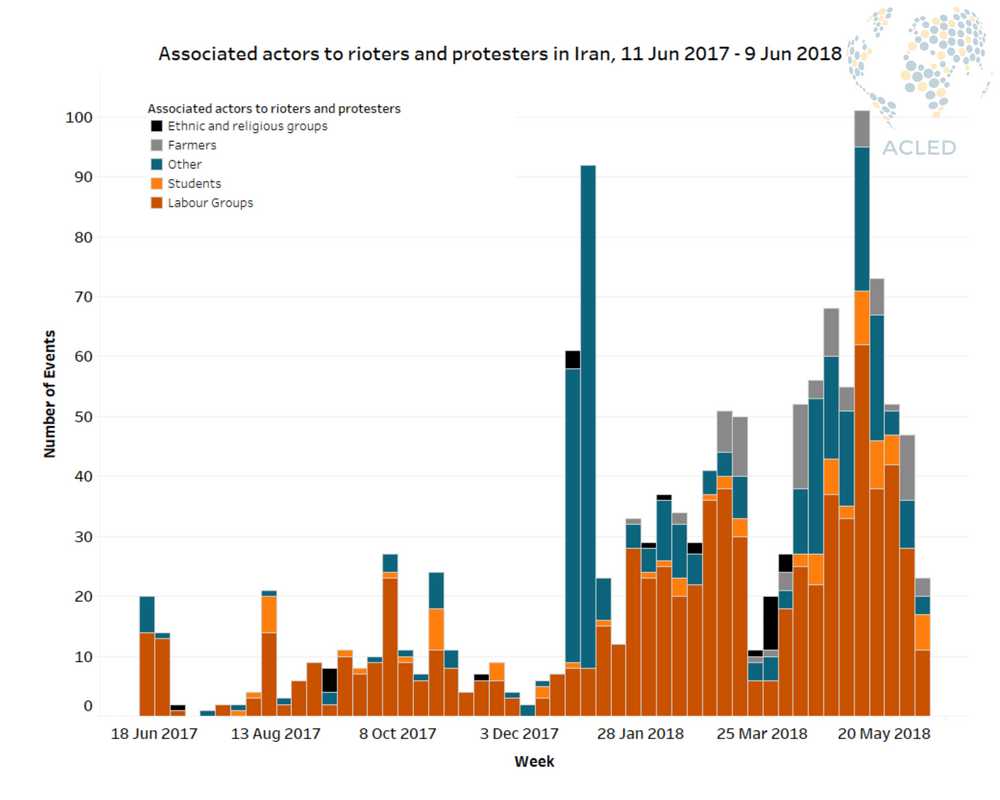

The overall weekly number of riots and protests has remained relatively high since early 2018 at the beginning of this wave of activism, when demonstrators were comprised largely of the ‘middle class poor’ — a “socioeconomically deprived [subset of the population with] … middle-class aspirations and qualifications” (Fathollah-Nejad, 3 April 2018). Working-class labourers, farmers, and teachers serve as the bedrock of these movements through at least June 2018. In recent weeks, they have made up well over half of all riots and protests. Groups such as factory workers, truck drivers, teachers, and municipality employees often seek months of unpaid wages or benefits like insurance. The chart below highlights the integral role of labour groups in riots and protests in Iran over a one-year period from June 2017 to June 2018.

The widespread participation of labour groups in demonstrations throughout Iran in 2018 may be related to crackdowns by police forces on striking workers, in addition to the unresponsiveness of employers toward their demands. Many groups end up striking or gathering in protests continuously or regularly when their demands are not met, suggesting that employers either do not have an interest in or do not have the means for addressing their grievances. The nationwide strike by truck drivers, for example, significantly affected the economy; while the government conceded a 20 percent increase in transport payments, it did not meet the protesters’ demand of 35 to 50 percent or end the strike (Radio Farda, 2 June 2018).

Workers and other groups are making their voices heard across the country as they sustain the demonstration movement that began in late December 2017. Chanting slogans such as “neither Gaza nor Lebanon, my life for Iran,” the protesters have signaled to the government that it should focus on providing stability and well-being to its citizenry rather than pursuing its regional ambitions (Fathollah-Nejad, 3 April 2018). Whether the government responds suitably to the demonstration movement will determine its lifespan and intensity.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskMiddle EastPolitical StabilityPovertyRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians