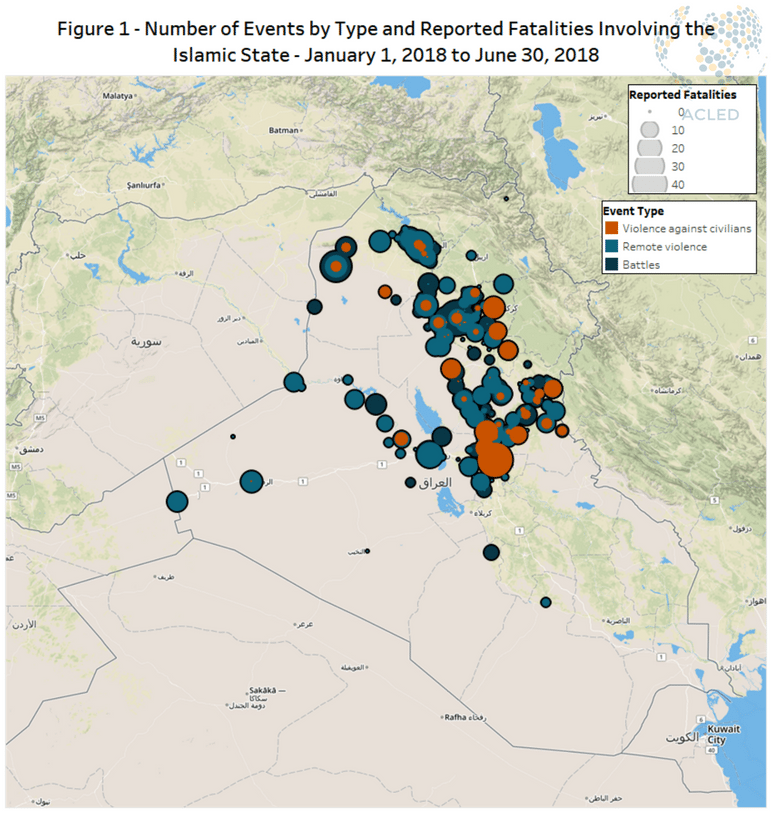

Following the protracted Battle for Mosul between October 2016 and July 2017, the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq was subsequently pushed out of its other major strongholds in Telafar and Haweeja. With the further loss of the border town of Al-Qaim, its last bastion in the Anbar Province, the proto-state in Iraq came to an end. Since then, the Islamic State has devolved from a group with the ability to seize and control territory back into an insurgency as it was recognized before the capture of Mosul. As a part of this process, IS has gradually reorganized in order to pursue what it refers to as a “war of attrition” (Wing, 2018). The insurgency is now concentrated along a geographic belt in Iraq which has been described as the ‘Colonization Zone’ (Knights, 2017), which is composed of largely rural Sunni-majority areas in the provinces of Salahuddin, Kirkuk, Diyala, and Nineveh, as well as the cross-sectarian outskirts of Iraq’s capital, Baghdad. A weaker version of the IS insurgency is also present in the Anbar governorate where political violence is of a more sporadic nature (see Figure 1).

In its new configuration, remote violence in the form of improvised explosive device (IED) attacks constitute the main modus operandi of IS, followed by combat engagements primarily with the Popular and Tribal Mobilization Forces (PMF/TMF), as well as their various constituent militias and tribes. IS militants also target their attacks against civilians primarily at Shiites; Sunni tribesmen perceived as close to government-aligned militias; people believed to be collaborating with Iraqi security forces; and individuals who represent local governance structures, including government officials, village chiefs, and tribal elders.

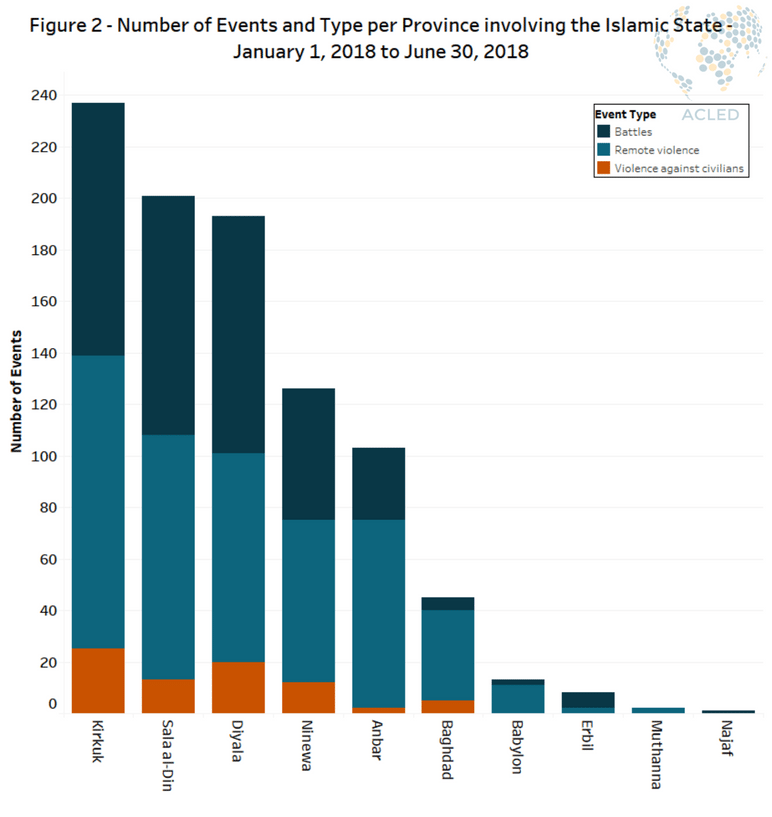

During the first six months of 2018, the most activity by IS militants was recorded in Kirkuk governorate, followed by Salahuddin, Diyala and Nineveh governorates, which fall along this ‘colonization zone’. These governorates are also bisected by the border between the areas administered by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and the central government in Baghdad. However, despite Iraqi security forces largely pushing IS out of its strongholds in Kirkuk governorate as recently as October 2017, the Islamic State has nonetheless managed to reconstitute itself in this area.

One important contributing factor that likely played into this reconstitution in Kirkuk governorate more broadly is the renewal of conflict between the central government in Baghdad and the KRG in Erbil following KRG’s referendum on Kurdish independence in late September 2017. This conflict centres on the disputed areas between their respective de jure jurisdictions, particularly those areas captured by the Kurdish Peshmerga forces since the Islamic State’s spread across much of the country in 2014-2015. This conflict reasserted itself most dramatically in the seizure of Kirkuk city from the KRG in October 2017 (New York Times, October 16, 2017). Since then, the continued tension in the borderlands between the KRG- and central government-administered areas of Iraq has led to a security vacuum, limiting the ability of the PMF, TMF, and the Federal Police, as well as the Peshmerga, to adequately secure them.

The typographical features of Kirkuk and the ‘colonization zone’ more generally are another important factor which offer advantages to IS militants by offering them areas where they can take refuge and stage attacks. These include the vast farmlands of Salahuddin, the forests and orchards of Diyala, and the far-reaching Hamrin mountain range, which cover large parts of Kirkuk, Salahuddin, and Diyala governorates (see Figure 2).

AnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringIslamic StateIslamist ViolenceMiddle EastPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceRioting And ProtestsViolence Against Civilians