Zimbabweans go to the polls on 30 July to select the president, members of parliament, and local government representatives. This election season is shaped by several marked differences from previous contests. Many of the parliamentary and council candidates are not party incumbents, and there are many independent candidates. Both of the main parties competing are under new leadership for the first time in decades, and both the MDC Alliance and ZANU PF are seeking ways to rebrand themselves. Both of the main parties are also highly factionalised by internal leadership contests that have been inadequately resolved.

There are also continuities in this election. The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission has been unable to establish credibility as an entity independent from ruling party influence within the government, and is deeply mistrusted by the opposition and civil society. Violence and intimidation continue to be used as mobilisation tools; although until now, intimidation is being used over overt violence. The economy is struggling.

What does this mean for the election and for politics in Zimbabwe in the next few months? The magnitude of the political changes over the past six months limits our ability to accurately predict the results of the polling. The main expectation is that ZANU PF will win the election, however, the party has a few key vulnerabilities, which will have to be managed during the election, in the case of a runoff, and in the months of consolidation following the election.

Zanu-PF will win

The question of ‘how much they will win by?’ is interesting, but ultimately subject to too much misinformation and pre-election manipulation to predict. The key factors that will ensure ZANU’s win are abuse of state resources and electoral manipulation.

Abuse of state resources:

- ZANU has overwhelming coverage in the state media, while opposition parties are expected to pay high sums of money, or are excluded.

- ZANU party officials distribute state food aid. There are continued reports of villagers required to produce their voting registration slips to obtain food aid.

- Command Agriculture is a rural agriculture scheme where all seeds and inputs must be purchased from the state and all food grown must be sold through the state. Command Agriculture is run by the military and provides a platform for intimidation and control.

Election Manipulation: The Zimbabwe Electoral Commission is supposed to be an independent commission, however, its relationship with ZANU PF is deeply compromised. Based on previous election patterns and issues that have been brought up thus far, these are some of the key mechanisms that ZEC will use to deliver a vote that favours Mnangagwa:

- The Voters’ Roll: As of 27 July, three days before the poll, the final Voters’ Roll has not yet been released, so there is no way to conduct an independent audit. ZEC released a preliminary Voters’ Roll, but refused to release the biometric data, which hindered independent auditors. Two independent audits were attempted, both flagged a number of critical issues. However, with no final Voters’ Roll, it is impossible to assess, and the legitimacy of the election is entirely undermined.

- Ballot Papers:

- Printing: After intense advocacy from civil society and political parties, ZEC agreed to allow them to partially observe the ballot paper printing process (from 20 metres away), however, when the observers raised complaints, ZEC accused them of interfering.

- Storage: ZEC refuses to disclose the details about storage and transport of ballot papers. If the observers are unable to track this process, there is no way to guarantee that ZEC is not over-printing ballot papers or stuffing ZANU votes into ballot boxes. There have already been rumours of flying ballot papers in from Georgia and of ZANU PF MPs carrying ballot papers in their campaign cars. With no clarification about storage and transport from ZEC, these rumours look highly suspicious and discredit the process.

- Polling Stations Layout: Midway through July, ZEC changed the layout of the polling station, so that voters are not concealed by the polling booth. ZEC argues that the Polling Officer needs to observe voters, in case they take photographs of their ballot papers. Following intense advocacy, ZEC has retracted this change of layout, however, photos from the training indicate that the Polling Officers are being trained to set up open polling booths, and the Election Officers’ Training Manual has not been changed.

- Results: There is no clarity about the process of counting and publishing the results.

Opposition, civil society, and independent observers have raised a number of other issues and problems with the way that ZEC is handling the election. Even for issues that could have been easily resolved with a clear answer and the provision of evidence, ZEC avoided responding, lambasted critics and refused to engage. Although ZEC’s new Chairperson, Priscilla Chigumba, was supposed to reform the organisation and rebuild its professional reputation, following previous Chair Rita Makarau’s strongly pro-Mugabe loyalty, she has failed to build confidence in the either the observers or the opposition. Moreover, the ZEC secretariat, which failed to deliver the 2008 results and managed the manipulation of the 2013 results, has not changed.

Intimidation is not working

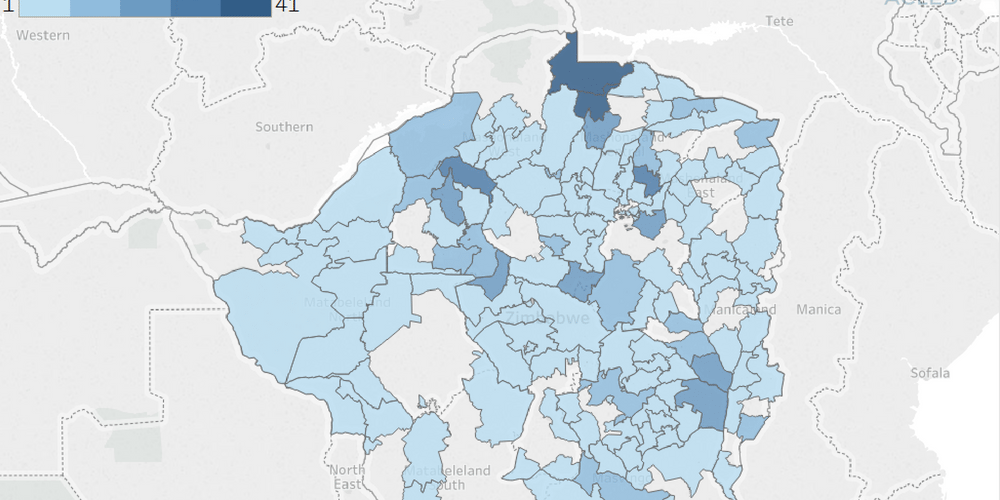

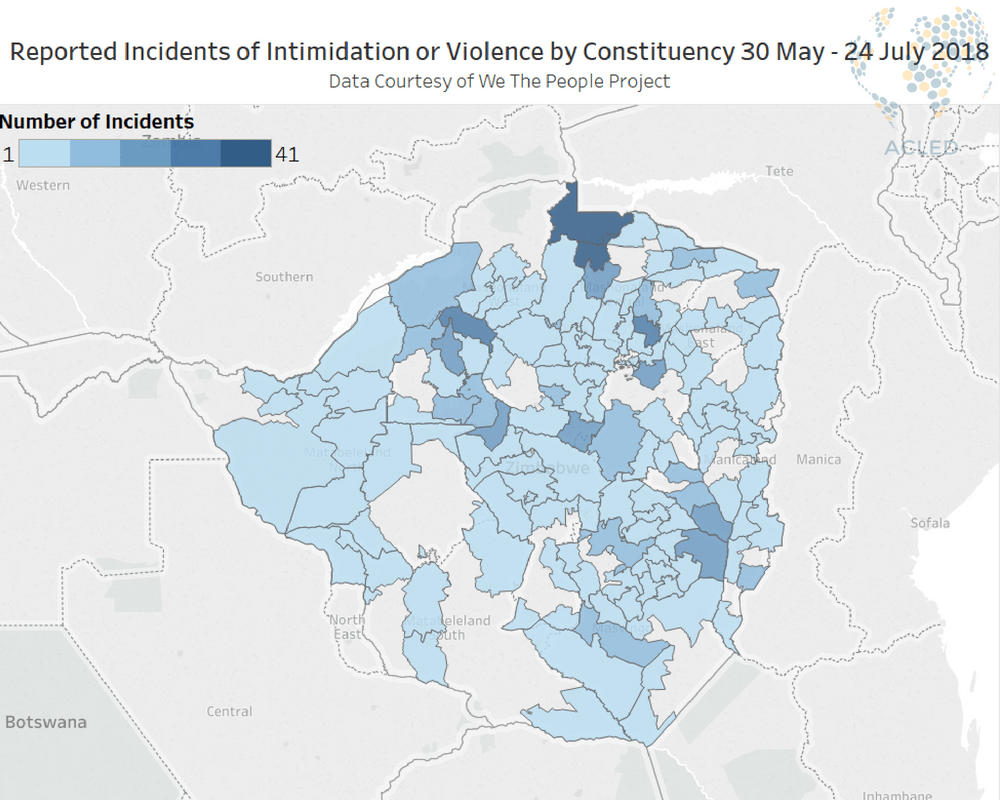

Different organizations collecting information on local disorder across Zimbabwe report significant levels of threats, intimidation, and attacks. The vast majority of the perpetrators are ZANU PF affiliates, mostly members of locally-mobilised youth gangs. The highest frequency of intimidation and violence is areas that typically have high levels of ZANU support. This indicates that there is a lot of anxiety within the party that supporters will defect.

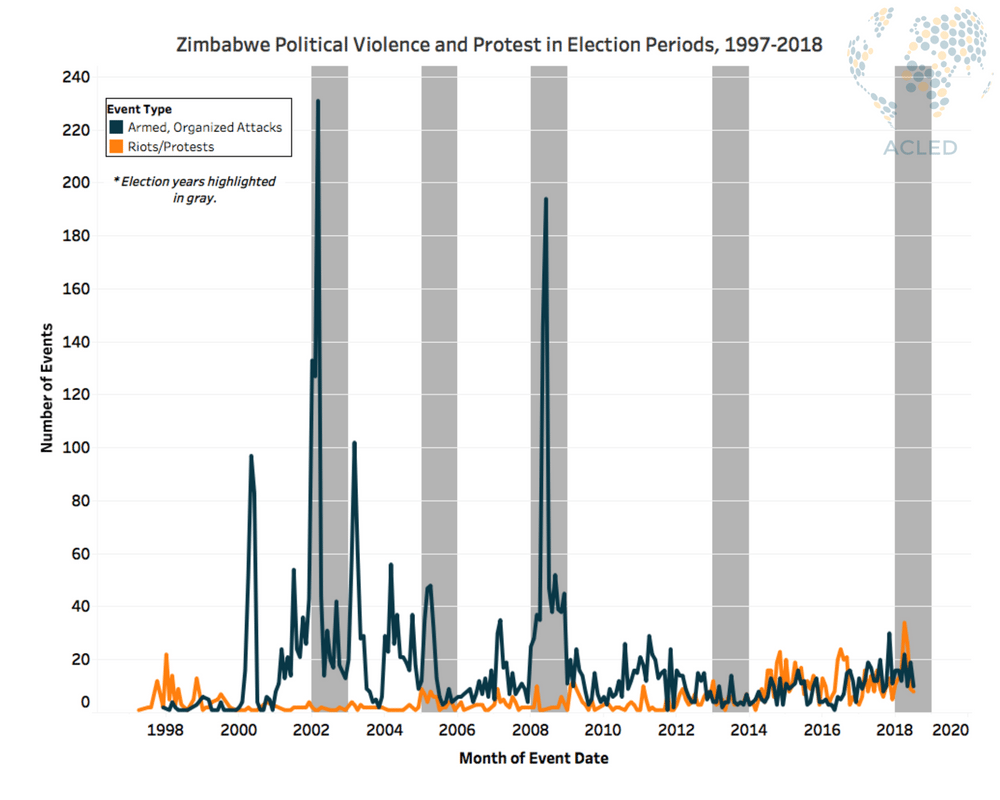

Because this information was not collated with the same level of detail for previous elections, a comparison is difficult. However, the patterns of activity do mirror previous pre-election periods (i.e. threats, intimidations and intermittent attacks), with the highest levels reported in the Mashonaland provinces (See map and graph of intimidation and violence reports).

There are two major differences to violence patterns from previous elections. Firstly, the fracturing of the opposition and the uncomfortable dynamics within the Alliance (such as having previous perpetrators of violence on MDC mobilisers running as Alliance MPs) has led to higher levels of violence reported within the MDC Alliance, between different opposition parties, and against ZANU PF supporters. Another key difference is that, where violence during previous election periods was highly organised and orchestrated from the most senior levels of ZANU PF, the violence during this period has been significantly more localised. Most incidents are related to local, rather than national dynamics, and the perpetrators are mostly mobilised by local politicians acting in their own interests (rather than national party interests) or are acting individually.

However, despite the widely reported intimidation, there have been record levels of open support for the opposition in polling. The most recent Afrobarometer suggested a minimal difference between ZANU PF and the opposition support (40% for ZANU and 37% for the opposition). However, this poll may be underplaying the urban/rural divide, which will almost certainly favour ZANU-PF.

Moreover, the narratives indicate that the high numbers of people reporting intimidation are doing so because they feel empowered to challenge it, rather than because they are cowed by the incidents. This nascent confidence is bolstered by the fact that the police have been marginally more responsive to reports, unlike in previous years, where they refused to file reports involving political violence. These responses are not systematic or widespread, but it is a step towards improvement. Overall there is an increased confidence in the population, in spite of the widespread intimidation.

Internal ZANU PF dynamics are changing

These elections mark a change in ZANU PF. How ZANU-PF changes depends on the results of the elections and the success of the strategies of different interest groups within and outside of the party during the elections.

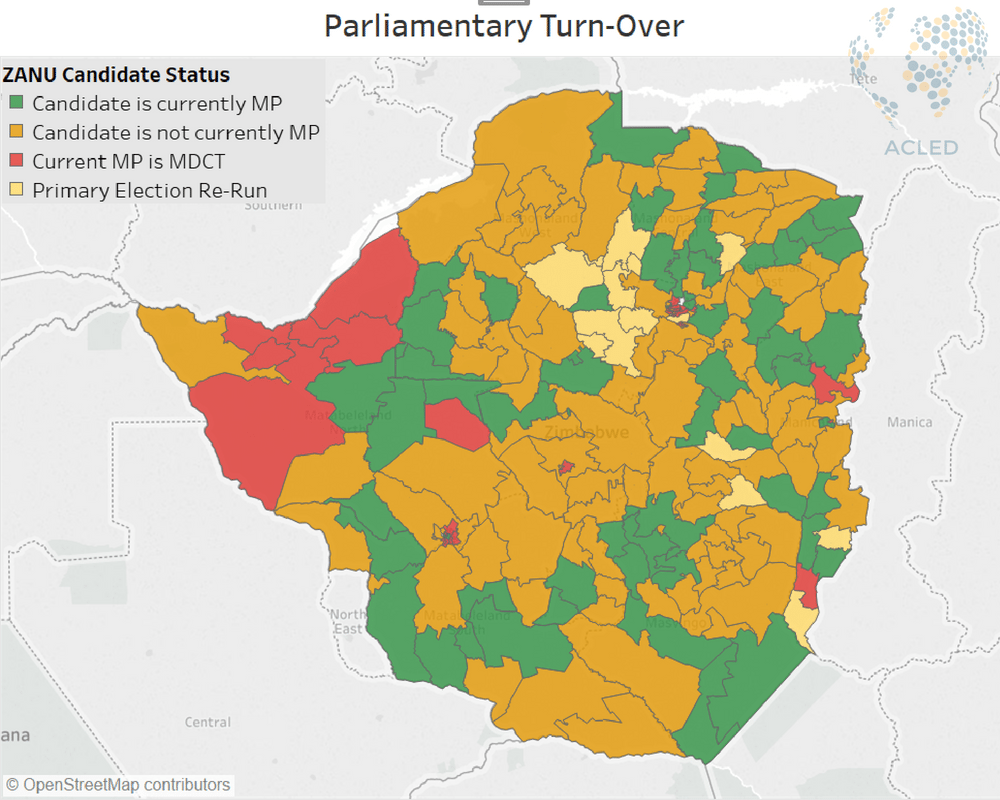

New Candidates: In the turmoil of the ZANU primary elections, there was a high turnover of candidates. Only 28% of the new parliament will be ZANU PF incumbent MPs. The new MP candidates are, for the most part, less experienced at political campaigning. They are also an unpredictable entity, as most do not have a parliamentary track record. The highest level of turnover is in Mashonaland West, Mugabe’s home province, which has experienced significant intra-party competition since the November coup.

Independents: 248 of the 1,649 parliamentary candidates are running as independents. Many of these independents are disgruntled ZANU PF candidates who lost primary elections or were forced out of the party. Prior to the 2018 election, independent candidates have not been successful (in the current parliament only 2 MPs are independents). If the former ZANU independents are able to leverage their local popularity to defeat the other candidates, ZANU PF will be eager to co-opt them back into the party. Existing outside of the ZANU PF patronage structure is uncomfortable, so these independents are likely to either re-join the party or to caucus with ZANU PF in parliament. However, their re-joining will be costly to the party.

Former ZANU PF supporters now running as opposition candidates: A number of former ZANU PF supporters are running as opposition candidates, either under break-away ZANU PF groups (such as Joice Mujuru’s Rainbow Coalition) or under the MDC Alliance.

- The break-away ZANU PF groups have been unable to sustain strong party structures or build widespread support – Between 2015 and 2018, Mujuru’s party split three times and the break-away groups are collectively polling at less than 5% of the vote. It is possible that if any of these candidates win, they might be co-opted back into ZANU PF, as their loyalties are notoriously unreliable, and the protection of a strong ZANU PF would be a more attractive option than a shifting fledgling party. The Mujuru allies were also mostly pushed out or defected from ZANU PF prior to the coup factionalism, so are less vehemently anti-Mnangagwa.

- The former ZANU PF candidates running under the opposition Alliance will be less likely to automatically re-join a Mnangagwa-led ZANU PF, because they were pushed out during the run-up to coup or in the immediate aftermath. These candidates are either strong Mugabe loyalists or strong G40 allies, so rebuilding connections with them will take longer, particularly if there is a strong anti-Mnangagwa protest vote on the 30 July, and the Mnangagwa machine feels threatened by this group. If the anti-Mnangagwa protest vote does not materialise, the party will be more prepared to absorb these candidates. The candidates are unlikely to remain loyal to the opposition Alliance, as there are already indications of tension, and, in some cases, violence, between Alliance activists and their new representatives.

The party organisation structures: This election has demonstrated significant contention and dissonance within the party organisation structures. Following the election, the party will need to resolve the issues that have emerged during the primaries and the campaign.

Party Commissar: Historically Commissar is one of the most powerful positions in the party. During his tenure, Saviour Kasukuwere used this position to develop a strong network of allies committed to blocking the ascension of Mnangagwa. The new commissar, Retired Lieutenant General Engelbert Rugeje, inherited the structures populated by Kasukuwere and has not successfully taken control of this important aspect of party control. Rugeje was deeply involved in the violence during the 2008 runoff, and is feared in the areas where he operated, but has not been a convincing Commissar. Prior to the primaries, ZANU PF needed to cleanse the structures of G40 supporters and Mugabe loyalists, or convince these individuals to act in the best interests of the Mnangagwa-led party in the upcoming election. Rugeje failed in both of these tasks. The Provincial Chairs who were replaced following the coup have been unable to consolidate their provinces and the G40 or Mugabe loyalists who remained in the party structures have failed to unanimously rally around Mnangagwa’s cause.

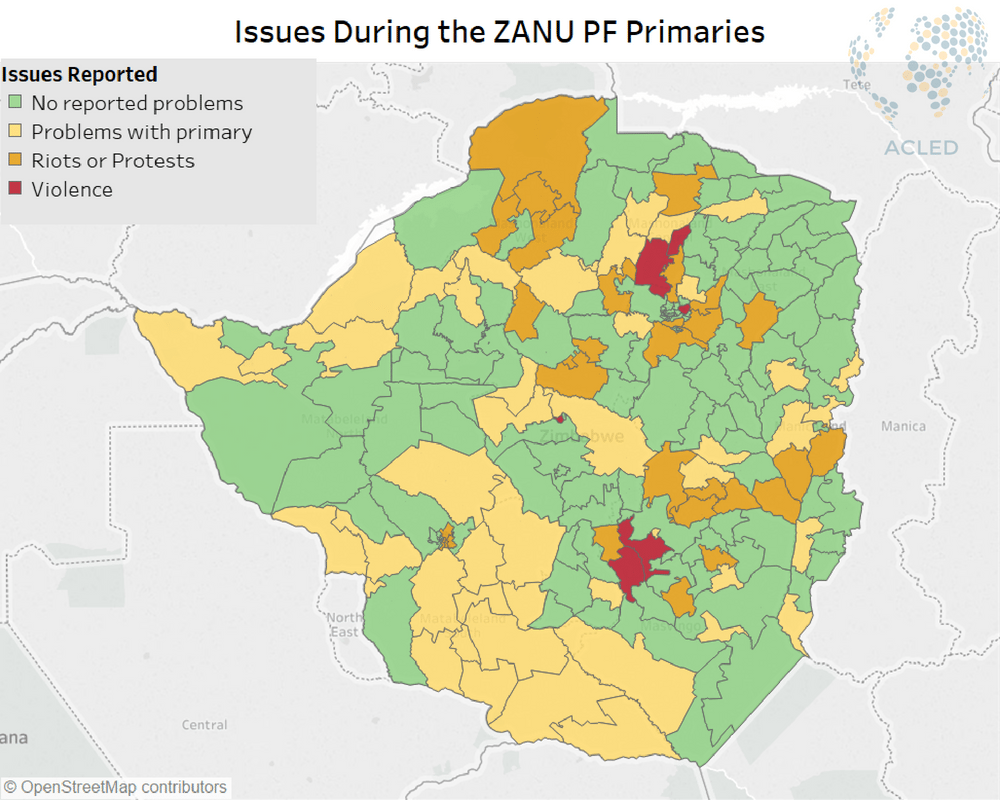

PCCs: The Provincial Coordination Committees are supposed to manage the ZANU PF primaries and run the campaigns in their provinces. They should be a key factor in implementing a strong party campaign at the local level. There has been considerable disarray within the PCCS during the primaries and campaign. (See the map for detail about problems during the ZANU PF primaries).

The Mashonalands are problem areas

ZANU-PF and the MDC Alliance have a chequered path to success in this election. The MDC alliance is likely to retain hold of the urban areas, and Matabelelands (North and South, although South was lost to ZANU-PF in some questionable elections results in 2013). Further, there is typically scattered support for the MDC (and now opposition Alliance) in different constituencies throughout the state. ZANU-PF often has a strong rural presence, but the issues pre and post-coup mean that particular areas are now more contentious. Indeed, Mashonaland – where significant issues were recorded in the 2008 election- is again a restive zone. These areas represent a crucible for Zimbabwe- the most densely populated, the most politically entitled, and the most prone to violence.

Mashonaland West:

Mashonaland West is Mugabe’s home province, so was likely to be a difficult area in the first post-Mugabe election. During the coup, Mashonaland West Acting Chair, Ephraim Chengeta was replaced by Ziyambi Ziyambi, a Mnangagwa ally, who was also appointed Minister of Justice in the new cabinet. However, there were high levels of tension between Ziyambi and the Minister of State for Mashonaland West, Webster Shamu, due to internal party politics coupled with the reality of local leverage: Shamu was originally expelled from ZANU PF with Mujuru, then readmitted to the party by Mugabe, then appointed Minister of State for Mashonaland West in Mugabe’s last Cabinet reshuffle, then reappointed to the same position by Mnangagwa. He was loyal to neither president but was too locally powerful in Mashonaland West to be ignored.

Shamu snubbed Ziyambi at official provincial events and upset the Mnangagwa faction by running against and defeating the newly appointed Mnangagwa loyalist leader of the Provincial Youth League, Vengai Musengi, in Chegutu East. He also upset the Mnangagwa loyalists by supporting his wife’s campaign against Chris Mutsvangwa in Norton, thereby causing Mutsvangwa to be defeated. Mutsvangwa considers himself a key Mnangagwa ally, who was denied the opportunity to hold a full ministerial position because he was not a sitting MP. He needs to win the Norton seat to occupy the position of power that he expects to occupy. Mutsvangwa contested the result of the primary, and he will run as the ZANU candidate. In late May, Shamu was fired from Cabinet, on allegations that he rigged the primary elections, he and his wife were then expelled from the party. However, his name was already on the ballot paper for ZANU PF, so when he was invited back into the party a few days later, he remained as the candidate. In July, a video circulated on social media in which Shamu instructs ZANU supporters not to vote for Mnangagwa.

Meanwhile, Dexter Nduna, the Mnangagwa ally appointed Deputy Chair of Mashonaland West in the mini-purge that removed Shamu, was arrested following his primary election. Nduna believed that his opponent, a friend of fired former G40 leader, Patrick Zhuwao, was a G40 plant, intended to undermine Mnangagwa’s chances. Nduna was chased away from a polling station by presumed G40 sympathisers, so opened fire on the crowd. He has been released, and he will run as candidate, but is likely to struggle to muster the full support of his constituency after his primary election.

Following a number of highly-contested primaries in Mashonaland West, 41 former ZANU PF supporters applied to run as independents in the parliamentary and local election campaigns. The PCC expelled all 41, including Walter Mzembi, the former Minister of Mining, who is linked to the Mugabe family and popular in his constituency, and former Deputy Minister of Education Godfrey Gandawa. Gandawa is running as an independent in Magunje constituency, where he is actively decampaigning Mnangagwa. ZANU PF is clearly concerned about Magunje, because it is one of the constituencies where a torture base has been confirmed to have been established (in the same show grounds that the 2008 Magunje torture base was established) Gandawa’s home was also raided by unidentified armed men, who abducted family members and threatened to assassinate him.

Mashonaland East

Mashonaland East is another volatile province. Reports from Mashonaland East PCC meetings say that the party strategy is incoherent. Following the coup, Chairperson Bernard Makokove was expelled and replaced with Joel Biggie Matiza, a Mnangagwa ally who had previously been chair. Matiza has been trying to steer the province back to Mnangagwa, but has had high levels of resistance from the grassroots structures and local G40 supporters. In Matiza’s own primary election, in Murewa South, there were riots, when it was discovered that the voters’ preferred candidate, Noah Mangondo, had been left off the ballot paper. ZANU PF supporters in Murewa South wrote to the Commissar complaining that Matiza was imposed on them by the Mnangagwa faction, and that they intend to vote for Mangondo, who is running as an independent.

In Gomoronzi, there were problems during the primary election when Petronella Kagonye, Minister of Labour and Social Welfare, arrived at the party headquarters and demanded to take charge of collecting the CVs for ZANU PF candidates. The local ZANU PF members rioted and physically removed her from the building. They accused her of being out of touch with the grassroots and imposing Harare politics on the district. She won the primary election, but there were further riots in Goromonzi South, accusing the Mnangagwa faction of rigging the primary in favour of their candidate.

Meanwhile, in Goromonzi West, the current MP, Biata Nyamupinga, a close ally of Grace Mugabe, was left off the ballot paper. Without Nyamupinga’s name on the ballot paper, the winner was Energy Mutodi, a Harare businessman who is a close ally of Mnangagwa. Nyamupinga will run as an independent candidate and is expected to take a number of ZANU votes with her.

The Security sector

Although the security sector and Mnangagwa were perceived to be very close following the November coup. Mnangagwa rewarded top security officials with key government and party positions, but since, this relationship has fractured. Mnangagwa and Chiwenga have clashed over important decisions, such as the suspension of ZANU PF party members and the firing of nurses and policemen. Mnangagwa is projecting a carefully moderated image of a reformer keen to bring international investment to the country. Chiwenga is less invested in this image and has the potential to derail Mnangagwa’s credibility. It is likely that Chiwenga will support Mnangagwa through the election, however, there have been key reminders to Mnangagwa that he needs the security sector to remain in power. Not least of these reminders was the explosion at a ZANU PF rally on 23 June, which was either planted by a faction of the military, or was known about by the military, who did not prevent it.

The security sector portrays itself as the un-corruptible body that safeguards political power in Zimbabwe, following their guarantee of Mugabe’s victory in 2008 and their central role in the 2017 coup. However, the security sector is not without its own divisions and factions, and the 23 June rally explosion indicates that the security sector is not guaranteed to act professionally in all circumstances.

The security sector needs Mnangagwa to win the election, however, it would be useful for the security sector if he does not win by an overwhelming majority, because this will force him to accede to their protection and acknowledge their influence. From this perspective, a runoff would suit the military, because it would enable them to reinforce their role as kingmakers.

Mnangagwa needs to win a safe majority in the election, not only to secure his international credibility as the elected leader of the country, but to earn himself the internal credibility of having been elected rather than owing his position solely to the military.

Conclusion: a bruised brand, an internal mess, and few solutions in sight

ZANU PF is a bruised brand. An interesting feature of the 2018 campaign has been the focus on voting for Mnangagwa, rather than voting for ZANU PF. The campaign posters focus on his face and his scarf, and the slogan is #EdHasMyVote. All of his campaign speeches have emphasised that he is a new candidate with new ideas (regardless of his 38-year history in government). By distancing himself from ZANU, Mnangagwa could be attempting to lay the groundwork for rebranding the party and redeveloping the structures after the election. A less tightly-loyal party would be better able to absorb successful non-ZANU candidates after the election and strengthen the party capacity. However, this rhetorical distance also reflects Mnangagwa’s distance from the local structures. Without a loyal and efficient Commissar and functioning supportive PCCs, he is less able to control the local dynamics, which is a vulnerability.

The MDC Alliance and ZANU PF have surprisingly similar campaign narratives – building a new Zimbabwe, developing the economy, creating jobs and business opportunities – and both parties present themselves as new and fresh alternatives to the ZANU PF regime. However, both parties are entering the election as unstable coalitions of interests. In the post-election period, the parties will need to consolidate their internal politics, and figure out whether and how they will absorb or coalesce with other political parties.

While there is a small possibility that the 30 July result will require a runoff, this election is essentially a runoff, as the levels of support for the 21 other presidential candidates that are not ZANU PF or MDC Alliance are negligible. This will mean that a runoff will require redoubled campaigning from both parties and will likely be a more volatile campaign than the lead up to the 30 July. But should a runoff not occur, the lower the result for ZANU-PF in the first election will increase the likelihood that the election period ends with a government of national unity.