The Coalition in Iraq and Syria was set up in September 2014. As the Islamic State (IS) made rapid territorial gains in Syria and Iraq, the United States (US), joined by nine other countries, announced the formation of the Global Coalition Against Daesh.[1] Its goal was to cripple and ultimately defeat IS. Since 2014, Coalition membership has grown to include 77 countries (as well as NATO) — the vast majority of which contribute to the campaign without any direct military presence.[2] Only a small number of countries have been actively involved in both Iraq and Syria through direct military campaigns against IS since mid-2014. Hence, the Coalition in Iraq and Syria is both a temporary political alliance around a common goal and a military operation.

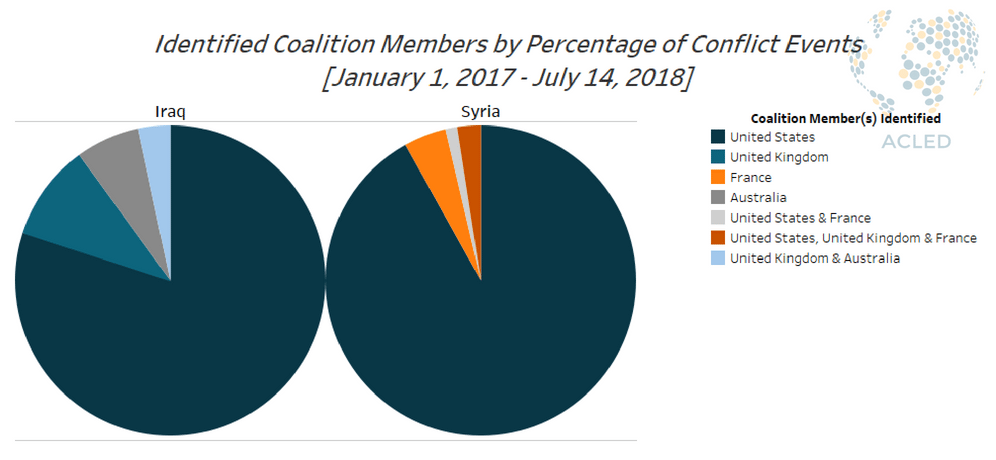

Actual military operations by the Coalition are often executed by the ‘Coalition’ — without it being precisely clear who exactly is responsible for the military events. ACLED data suggest that a stunning 97% of reported Coalition activity in Iraq and 85% in Syria are not attributed to a specific Coalition member. When specific members are identified, however, US forces constitute the majority of events, responsible for 80% of Coalition activity in Iraq and 92% in Syria (see figure below), suggesting that even in cases where specific actors are not explicitly named, it is likely that the US continues to make up a majority of these as well. Other active actors in these two countries vary: the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia are active in Iraq, for example, while the UK and France are active in Syria.[3]

While the Coalition shares the common goal of defeating IS across Iraq and Syria, its modes, means, and tactics vary across the two contexts. The distinct local features of each conflict take precedence over a standardized and comparable foreign military campaign across both countries.

The different nature of the conflicts in Iraq and Syria impact the varying degrees of involvement by the Coalition; namely, in Syria, the Coalition engages with only a fraction of the total conflict. In Iraq, the Coalition has been involved in approximately 16% of the total reported events in the country. In Syria, this number is closer to 4%. This highlights how Syria is host to a number of varied conflict arenas. In Iraq, 78% of all conflict events involve IS; in Syria this number is closer to 17%. Again, this points to the complexity of the Syrian conflict; the war in Iraq is less multidimensional than in Syria, which aids in making external engagement less complex.

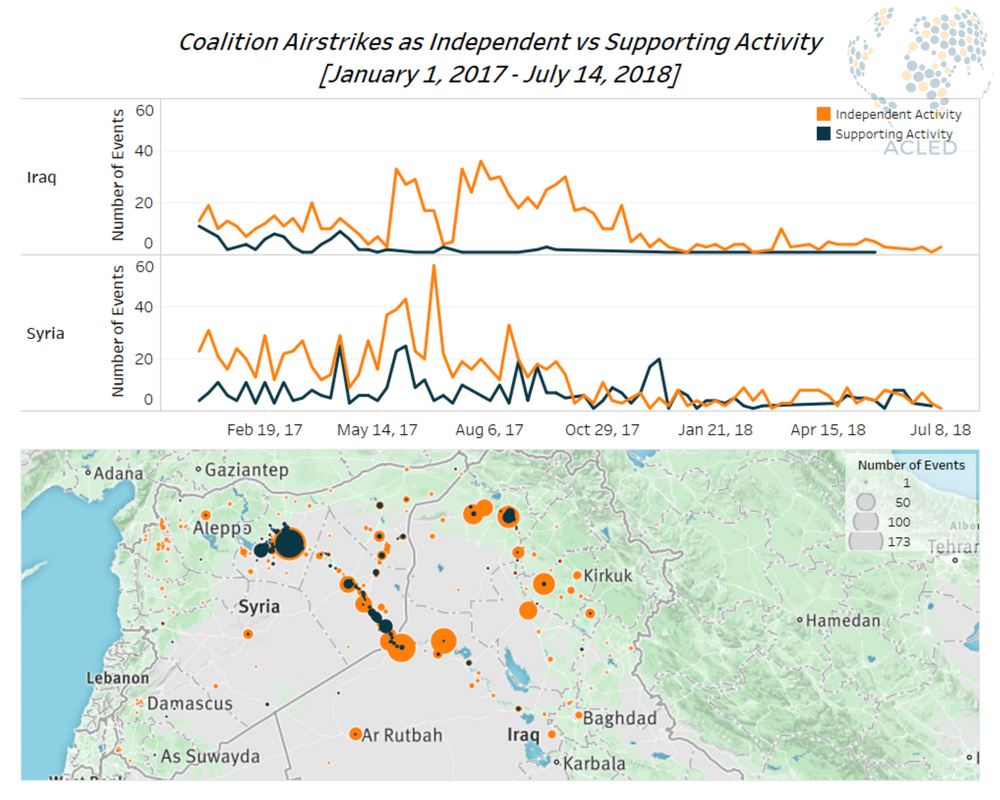

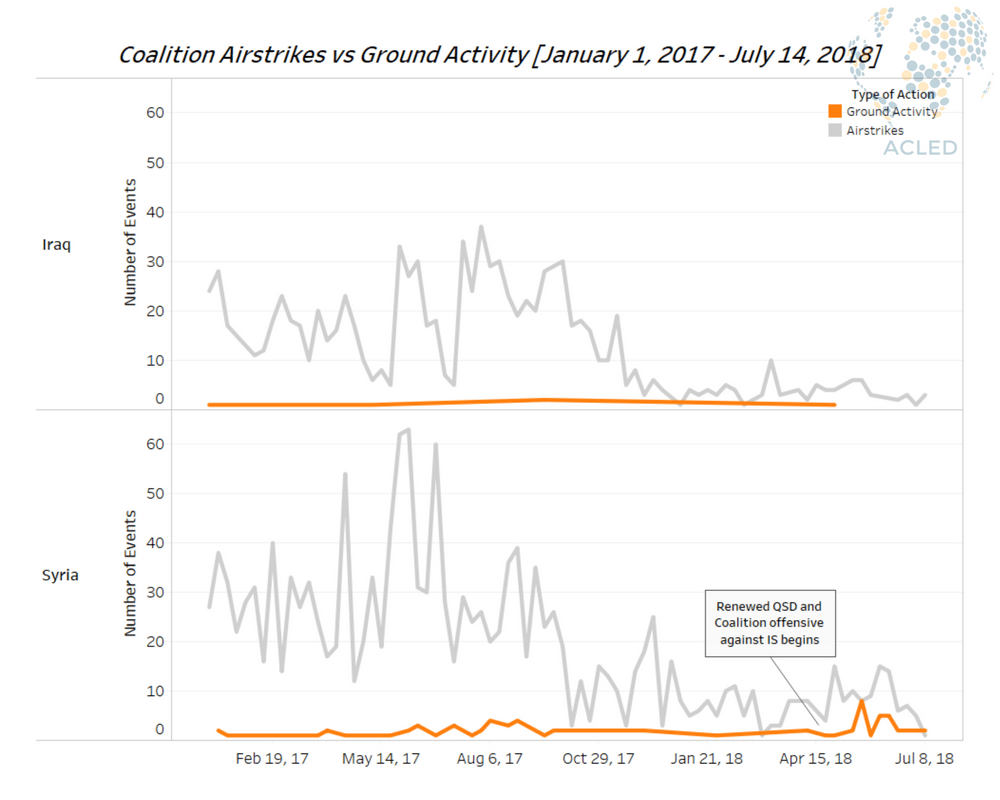

Different alliance patterns in the two countries contribute to the ways in which the Coalition allies with local ground forces, impacting the Coalition’s autonomy or lack thereof. In Iraq, the Coalition operates mostly on its own, using airstrikes to combat IS ground presence (see figure below). In fact, only 12% of all Coalition activity was carried out in support of allied troops on the ground in the country. In those allied instances, the Coalition’s primary partner was the Iraqi forces,[4] partly as the Coalition forces became active in Iraq under the invitation of the Iraqi government. The Coalition has also provided the Iraqi military with extensive military training and logistical support. In Syria, on the other hand, the Coalition’s primary partner[5] is the Syrian Democratic Forces (QSD), a mainly Kurdish group led by the People’s Protection Units (YPG), which is the official military force of the Kurdish Democratic Federation of Northern Syria. A higher instance of Coalition airstrikes occur to support allied ground forces in Syria, where Coalition strikes were carried out in support of ground forces in around 32% of all events (see figure below).

Different modes of violence characterize Coalition activity in Iraq and Syria; activity in Iraq is almost exclusively an air campaign used to ‘soften the battlefield’ before major battles, while activity in Syria shows increasing ground activity (see figure below). The presence of US Special Forces ground troops throughout the battle for Ar-Raqqa city accounts for a number of Coalition ground activities in Syria. Though additionally, Coalition troops have remained an active element of anti-IS ground operations in Syria as QSD and allied forces have attempted to push the group eastward. There has been an increase in the instances of Coalition ground shelling and engagement in battles since April following a renewed offensive against IS near the Iraqi border.

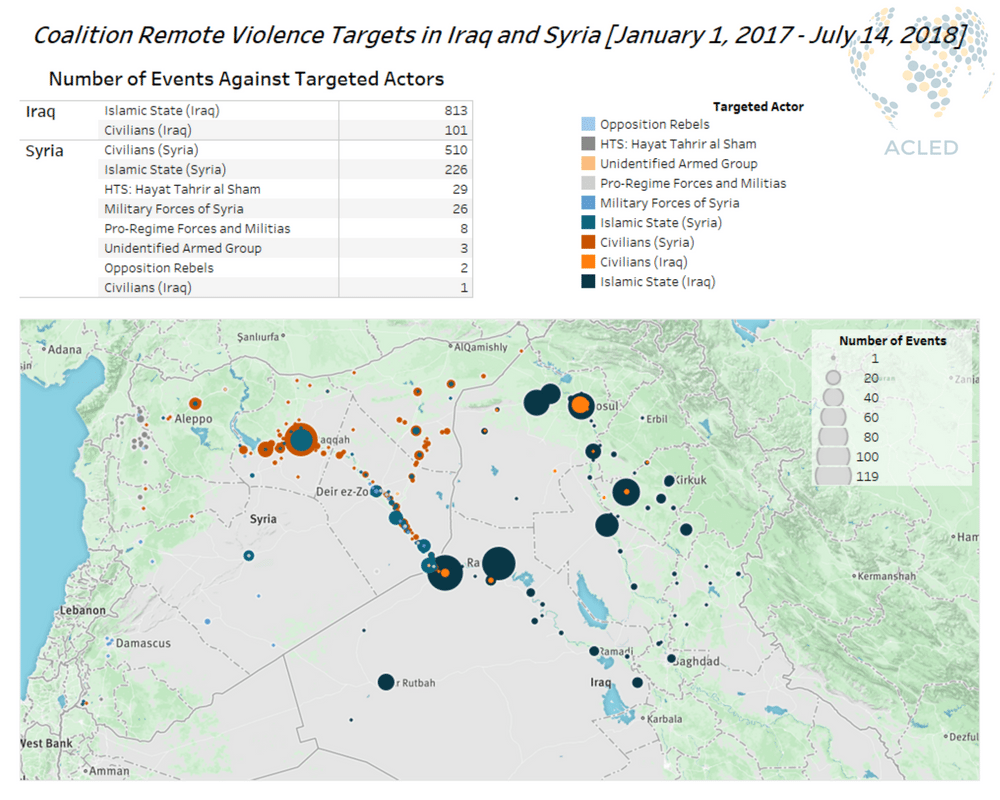

The targets of violence in Coalition activity vary by context; in Iraq, Coalition activity has exclusively targeted IS, while in Syria, Coalition activity has targeted other groups, including the Syrian regime and its allies. This is a result of the different conflict contexts. The majority of conflict in Iraq centers around IS. In Syria, IS constitutes only one of several key conflict actors. For example, remote violence carried out by the Coalition in Syria targeted and/or impacted a wider range of actors relative to in Iraq (see figure below). Not including instances in which civilians were the primary casualties of Coalition strikes (more below), Coalition remote violence in Iraq exclusively targeted IS, closely mirroring the Coalitions’ identification of IS as its sole official target within the country. Coalition targeting of armed groups in Syria, while primarily focused on IS, shows that the Coalition has occasionally strayed beyond its mandate to fight IS by targeting other groups as well, such as the former Al-Qaeda affiliate, Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS). More significantly, conflict with the Syrian regime and its allies has been a consistent undercurrent of Coalition activity in Syria as both Coalition and regime forces operate against IS in the northeast and as the Assad regime has consistently rejected the Coalition’s presence in the country as an illegitimate assault on the regime’s territorial sovereignty.

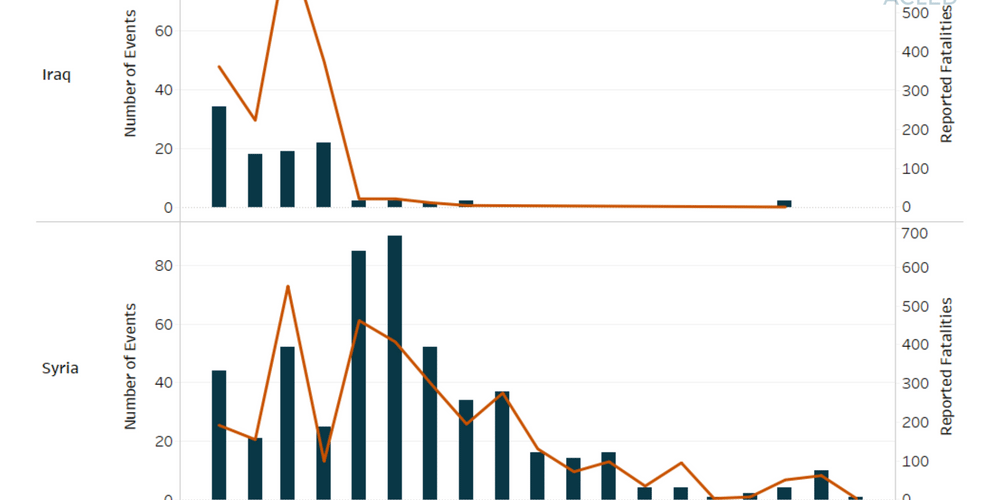

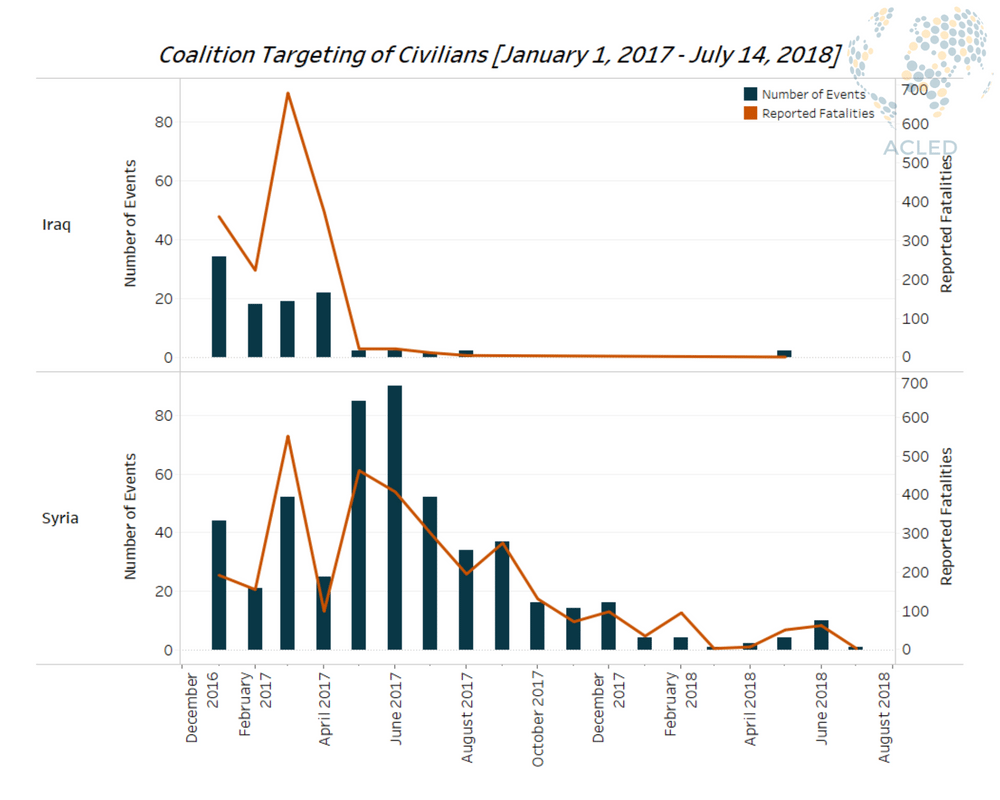

Lastly, civilian targeting and reported fatality rates differ across Syria and Iraq; namely, in Syria, Coalition activity has resulted in five times as many instances of civilian targeting as in Iraq. Coalition remote violence activity in Syria has been indiscriminate in ensuring that only military targets are hit. Civilians were reportedly hit more than five times as often in Syria than in Iraq by Coalition strikes, with a fatality rate almost two times higher (see figure below). While civilian casualties from Coalition activity in Iraq seem to be concentrated around the sites and timelines of major battles, civilian casualties stemming from Coalition activity in Syria are more geographically widespread, occurring not only along the frontlines of IS territory on the Euphrates River, but also occurring across eight of Syria’s fourteen governorates. This targeting of civilians in IS-held areas of Syria through seemingly indiscriminate remote violence has resulted in well over 3,000 reported civilian fatalities. These high numbers of civilian fatalities have not only led to international criticism of the Coalition’s activities in Syria but have also contributed to tensions and resentment with local populations — those who the Coalition is attempting to liberate from IS control.

What do these differences mean for Coalition activity in Iraq and Syria in the near future? Foremost that the dynamics will remain different between the countries. The fight against IS in Iraq is nearly over, with few incidents still reported. In Syria, however, the Coalition will remain active in the near future for three reasons. First, there has been a recent uptick due to a new joint QSD-Coalition offensive against IS in southern Al-Hasakah and eastern Deir-ez-Zor. Despite the “official” defeat of IS there are still IS-controlled villages in these and other areas of the country– mainly in Al-Hasakah alongside the Iraqi border — and dislodging them has proven to be difficult. Second, a new Coalition battlefront in Syria may be Idlib province, which has seen increased IS activity in recent months and where some previous and potential future Coalition targets are based (like HTS and other radical Islamist groups). Moreover, the very fragmented nature of the Idlib fight (with Turkish, Kurdish, Regime, Local, Islamist, Western, Iranian, and Russian interests all at stake) will mean a complicated game of chess to protect Coalition interests, whether the “final battle” for it is played out militarily or politically. Third, the Coalition has been a vehicle for various (Western) states to ensure that they continue to have a stake in the conflict – primarily through the backing of QSD which is currently only second to the regime in scope of territory held in the country. With the Syrian regime (backed by Russian and to a lesser extent Iranian support) quickly closing in on the remaining rebel-held areas, the Coalition will continue to be active in Syria in the near future in order to keep its seat, through QSD-held territory, at the table. Therefore, it is unlikely that the Global Coalition Against Daesh will be dissolved any time soon; rather, the difference between Coalition operations in Syria and Iraq will only become more pronounced.

This piece is part of a special series with a focus on coalitions in the Middle East. For more information about the series, please refer to Special Focus on Coalition Forces in the Middle East.

[1] These original members include the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Canada, Germany, Poland, Denmark, Italy and Turkey. “Daesh” is the Arabic acronym for The Islamic State and a name that carries a more negative connotation than IS or ISIL.

[2] The level of involvement of these partners varies greatly, with some minimally committed through activities such as countering IS propaganda, others committed to providing humanitarian aid or stopping the flow of foreign fighters, while a smaller number provide military aid and logistical support (The Global Coalition, 2018).

[3] Prior to 2017, Netherlands, Norway, Bahrain, Jordan, Canada, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates were also active (Drennan, 2014).

[4] Including the Iraqi Air Force, Army units such as the Counter-Terrorism Service, the Kurdish Peshmerga, and the Popular Mobilization Forces, as well as the Iraqi Police force, including its Rapid Reaction Force.

[5] When operating against IS in areas outside QSD’s traditional territorial reach, the Coalition had worked alongside other Free Syrian Army rebel groups such as Lions of the East Army and Ahmad al Abdo forces against IS.

AnalysisCivilians At RiskConflict MonitoringMiddle EastPolitical StabilityRemote ViolenceViolence Against Civilians