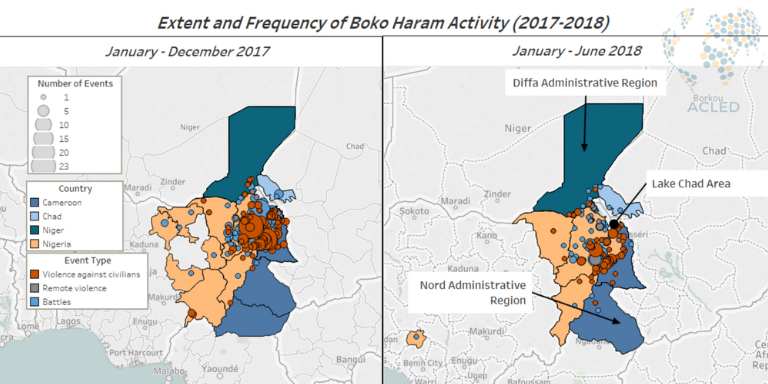

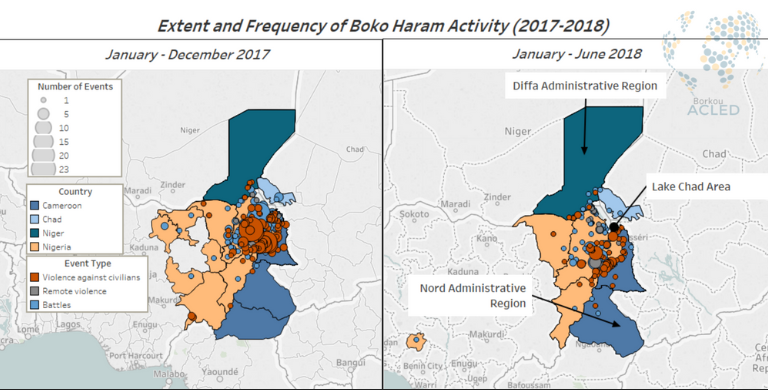

The military’s systematic hallowing of Boko Haram has caused a diminished foothold within Nigeria and may have accelerated lingering internal disputes. From 2016-Present, the Nigeria-Cameroon joint operations of Lafiya Dole and Last Hold have placed Boko Haram into a defensive posture, losing almost all Nigerian-controlled territory and limiting activities to remaining camps surrounding Lake Chad (Anadolu Agency, 21 April 2018). Consequently, Boko Haram has largely moved operations eastwardly. Activities in January through June 2018 have reached deeper into the Nord Region of Cameroon, as well as into the Diffa Region of Niger. Comparatively, movements in the central Nigerian States of Jigawa, Kano, Gombe and Plateau have ceased in 2018 (Figure).

Expressing confidence in their successes, the Buhari government declared Boko Haram “completely defeated” in early 2018 (Premium Times, 4 February 2018), and soon after entered a “post-conflict stabilisation phase” in the military’s north-east operations (News24, 7 July 2018). Despite heavy losses, Boko Haram’s offensives in June and July 2018 demonstrated a tempered ability to effectively engage military forces, a practice not done regularly since 2016. A mid-July 2018 attack on a military base in Jilli, Borno State contributed to the first territorial gain of the group since April 2018, causing the highest number of reported fatalities (31) in a single non-civilian attack in over two years (ICIR Nigeria, 17 July 2018).

Compounding Boko Haram’s slow collapse may be the growing ideological split within the group. Following the Abubarku Shekau’s rejection by Islamic State command in 2015, Abu Musab al-Barnawi – a top Shekau lieutenant – was appointed leader by Levant leadership. Shekau was declared illegitimate, and in turn stated Barnawi was attempting a coup against his authority (The Sun, 17 July 2018). Further pressing Shekau, the Barnawi faction has made a notable public relations push throughout 2018, providing basic amenities to area residents and stating their forces would not deliberately attack civilians (Reuters, 30 April 2018). Measurable regional loyalties are yet to be borne, though many Borno residents are beginning to claim a positive view of Barnawi’s faction (Global Institute, 24 May 2018).

It is currently unclear how joint Nigerian and Cameroonian forces may exploit this division while balancing Barnawi’s fledgling popularity. Despite Boko Haram’s current limitations, the group has demonstrated that they still have an ability to carry out significant attacks; future gains may depend on the coalition government’s strategic defence planning. Measures may include blocking social media and activating counter intelligence campaigns (City University of London, 25 January, 2018).