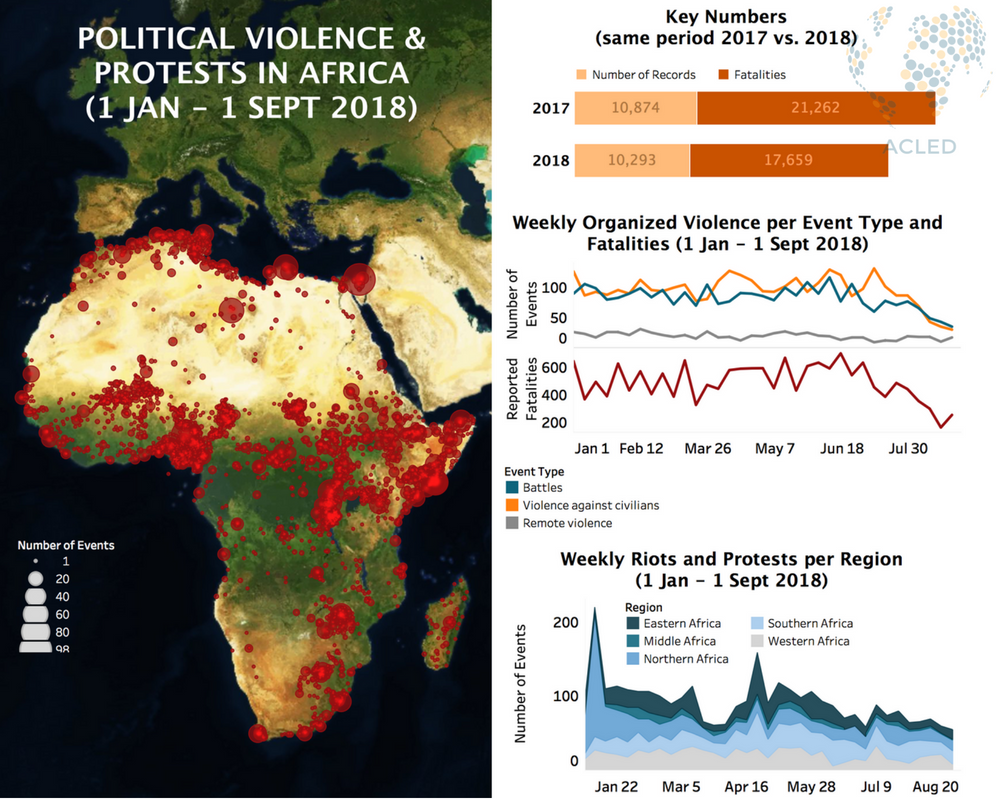

There was an overall downward trend in the levels of organised violence and protests on the African continent during the month of August 2018 compared to the rest of the year. There are fewer reported events than is typical for August based on previous years, but this pattern may still be reversed due to reporting lags. Significant developments still spanned a number of countries in August 2018.

First, tensions rose significantly across a number of contexts where elections were held, or are due to be held, in the coming months. In Zimbabwe, violence dramatically escalated following the election of Emmerson Mnangagwa from the ruling ZANU-PF party in the July 30th presidential election. The opposition Movement for Democratic Change (Alliance) challenged the results through legal and street actions, resulting in a clear shift from small intra-party incidents prior to the elections to widespread and highly organized violence and intimidation by the military and ZANU-PF activists. Following a series of raids on people’s houses, hundreds of opposition and civil society figures went into hiding. Further arrests were made and violence perpetrated ahead of and following the Constitutional Court’s ruling on the MDC legal challenge on August 24th. The MDC were unable to provide substantive proof of election rigging, and Mnangagwa was formally inaugurated on August 26th.

In Mali, President Keita was re-elected in the second round of polls on August 12th. During both election rounds, presumed Katiba Macina militants intimidated and assaulted a large number of voters and election officers, as well as destroyed voting material and stations, primarily in the Mopti region. On August 18th and 25th, dozens of protests erupted nationwide to denounce electoral fraud after the results of the second round were announced.

In Mauritania, arrests and violence also rose ahead of the parliamentary, regional and municipal elections of September 1st. In particular, a rare ambush was carried out on a Mauritanian military patrol in the North-East, near the border with Mali, on August 10th. After the elections, all opposition parties denounced fraud, irregularities and bad organization. Back in April and May 2018, members of the radical opposition National Forum for Democracy and Unity (FNDU) protested on several occasions already against the setting up of the independent electoral commission, which they considered corrupt.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), presidential elections are due to be held in December 2018. Tensions rose during the course of August as the government cracked down on the opposition after President Kabila declared that he will not run in the elections. Protests erupted in Lubumbashi on August 6th after the leader of the opposition platform Together for Change –Moise Katumbi– was twice prevented by authorities from returning to the DRC to submit his candidacy for the elections. The police responded violently to the protests, firing live bullets that killed a young boy. Later in the month, further protests erupted after the electoral commission announced that six other opposition contenders out of the 25 registered ones were barred from running in the elections, including Jean-Pierre Bemba, leader of opposition Movement for the Liberation of Congo (MLC), who was acquitted by International Criminal Court in June and has a powerful support base. The commission’s decision on the parties’ appeal against its decision is likely to influence the level of violence in the country over the next weeks.

In addition to election violence, militants sustained high levels of violence in northern and middle Africa. In Libya, the security framework collapsed as intense fighting erupted in Tripoli on August 25th between the Seventh Brigade and a coalition of militias operating under the UN-backed Government of National Accord. Around 30 fatalities were reported from the fighting, which was still ongoing as of September 1st. In both Libya and Chad, several rare incidents involved two Libya-based Chadian rebel groups during August. In Libya, Islamic State militants overran a Front for Alteration and Harmony in Chad (FACT) camp in the area of Fuqaha (Al Jufrah) on August 3rd. In Chad, militants of the Military Command Council for the Salvation of the Republic (CCMSR) launched two offensives on the Chadian forces in the area of Kouri Bougoudi (Tibesti) near the Libyan border and managed to overrun a base on August 21st. Chad reportedly launched airstrikes in the areas of Kouri Bougoudi, Miski and Yebbi-Bou in response, wounding civilians. These were the first CCMSR offensives in a year.

Meanwhile, there was an upswing in violence in Burkina Faso and Egypt in August. In Burkina Faso, attacks on state forces by Islamic State, Ansaroul Islam and other factions spread to areas outside of the Sahel region. Some of the deadliest IED attacks Burkina Faso has known were perpetrated against security forces escorting employees of the SEMAFCO mining company or sent in reinforcement in the areas of Nassougou and in Kabongo in the Est region. In Egypt, the Islamic State militants stepped up their attacks against the state forces in Sinai, urging the government to bolster its counterinsurgency operations.

In Algeria, significant security developments during August included the renewed fighting between Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the Algerian military in Skikda, though AQIM defections were recurrent throughout August, following a deal reached for their surrender by the government with the help of France. Significant reshufflings also took place within the military, with almost all senior commanders either sent into retirement or put into different positions by President Bouteflika as of the end of August.

Nigeria responded to a wave of attacks by “cattle raiders and armed bandits” in the state of Zamfara that allegedly killed 42 people end July, whilst a Parliament blockade by security operatives on August 7th suggested the rise in political maneuvering ahead of the 2019 elections. The incident occurred after the Senate president, three governors and 40 lawmakers defected from the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) to the main opposition.

In Ethiopia and South Sudan, new opportunities for conflict resolution arose in August as peace agreements and demobilisation and reintegration deals were concluded with a range of insurgent factions in both countries. In South Sudan, all the conflict parties bar one (the National Salvation Front, due to follow suit) signed the final version of the Khartoum Declaration of Agreement on August 30th after a month of relative calm. Peace agreements have been signed between the factions before, but the significant difference here is that the opposition does not have much leverage left. In Ethiopia, the gains made on the political stage were offset by tensions stemming largely from the Somali region. The growing tensions between Addis Ababa and Jijiga –particularly over the leadership of the President of the Somali Region, Abdi Illey, and the lack of accountability of the Liyu police paramilitaries under his command–resulted in clashes on August 3rd between soldiers and the Liyu police. They were followed by three days of organized riots and violence by Heego youth seemingly loyal to Iley. Iley resigned from his post soon after and was placed in custody in the capital. Meanwhile, the Liyu police paramilitaries intensified their assault on border areas between the Oromia and Somali regions. They attacked nine villages in Babile on August 10th, killing 23 civilians, and again in Meyumuluke woreda on (or around) August 12-14th, killing another 60. Two last notable developments in Ethiopia in August were the arrest of over a thousand people suspected of involvement in the recent violence in the country in a few waves throughout the month, and the continuing peace negotiations with Eritrea.

Lastly, some key trends in the typically more calm places of Uganda, Kenya and South Africa saw governments responding to perceived threats. Uganda had a violent response to the waves of popular support for MP Bobi Wine; there are high levels of mob- and gang-related violence in Kenya and South Africa. In Uganda, chaos erupted during the parliamentary by-elections in Arua on August 13th as Bobi Wine supporters demonstrated in parallel to the presidential visit. The presidential guard opened fire on the crowd, killing Bobi Wine’s driver, and arrested over 30 people, including him. His treatment in detention sparked violent protests and deadly state security responses in Kampala and other towns in Uganda throughout August. This is reminiscent of how Kizza Besigye was treated during his time as the prominent Museveni opponent. Three people died in Mityana (Mubende), Katwe (Kampala) and Bukalagi (Mpigi) on August 20th and 23rd as police fired live ammunition to disperse groups of protesters and rioters. Whilst reflecting Museveni’s unassailable grip on power in Uganda, these events also revealed his lack of popularity among a growing constituency of disaffected young people, especially in urban areas.

In Kenya, reports emerged in August of brutal gang attacks in Butere (Kakamega) by a group called “The 42 Brothers”, whilst police killed several members of other gangs in operations in Nairobi end August. In both Kakamega and Nairobi, state representatives (an MP and the former finance county executive of Garissa county) escaped assassination attempts in mid-August. Another relevant development was the arrest of the Deputy Chief Justice of Kenya on August 28th on charges on corruption and tax evasion charges, amidst tensions between the presidency and the judiciary relating to the annulation of the recent presidential election results.

In South Africa, although events continue to be dominated by service delivery protests and riots, there has been a typical flare up in mob violence. In mid-July, at least four people were killed in separate mob justice attacks in Dunoon area of the City of Cape Town. Similar incidents were reported in August in Cape Town, Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape and North West. On August 22nd for instance, about 40 residents in Mandalay stoned three men to death after they were caught breaking into a house. Along the same lines, xenophobic violence re-erupted last week in poorer urban areas and townships of South Africa’s metropoles. In Soweto in Gauteng, the residents went on rampage and looted dozens of foreign-owned shops around the township. Two people died in the violence.