Violence associated with Fulani militias is on the decline since reaching a peak in January 2018. However, this decline is likely driven by the seasonality of violence. Shifts in the type of violence associated with Fulani militias in 2018 thus far suggest that there will be increased targeting of civilians and clashes with the government in coming months.

January 2018 marked a five year high in the number of events associated with Fulani militias in Nigeria. Within January 2018 alone there were 91 violent events associated with Fulani militants, resulting in a reported 302 fatalities. These fatalities include members of the Fulani militias, who have also been the target of attacks by other militias in the country. Violence between Fulani militias and community militias is a long-standing feature of the conflict landscape in Nigeria, however, the intensity of this violence in 2018 thus far is an anomaly.

Though much remarked upon, conflict involving Fulani militias defies easy classification. Fulani militias are not a centralized armed group, operating under a specific agenda. Much of the violence involving Fulani militias centers around disagreements between pastoralists and farming communities, which prompts many to refer to the violence as ‘farmer-herder conflict.’ Demographically, the majority of Fulani are Muslim, leading others to describe the violence as a religious conflict. The variety of terms used to describe violence involving Fulani militias alludes to the ethnic, religious, and material diversity of Nigeria’s Middle Belt, where much of the conflict takes place. We use the term “Fulani militia” at ACLED because it is the least biased of terms.

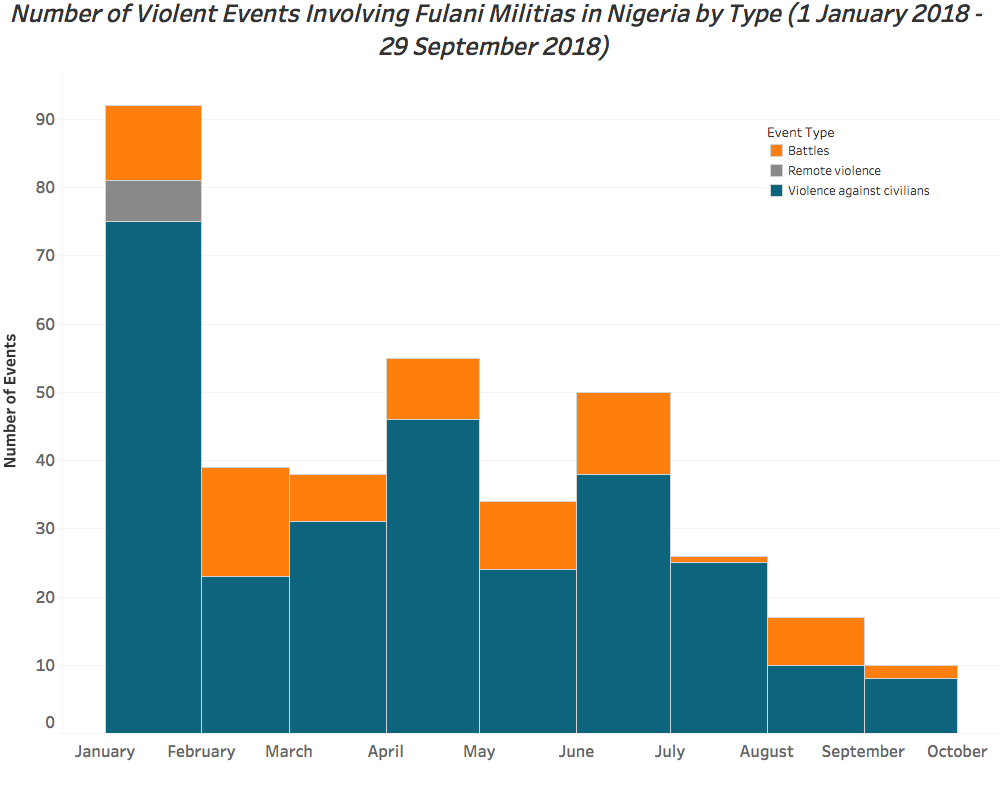

Since the start of 2018, violence involving Fulani militias has resulted in more reported fatalities than Boko Haram over the same period; since the start of 2018, 1,868 fatalities have been attributed to conflicts involving Fulani militias (both in conflicts instigated by such militias and in attacks on its members), as compared to 1,536 reported fatalities attributed to fighting involving Boko Haram. Since peaking in January, the number of violent events has tapered off; in September, there were 10 events associated with Fulani militias, which were associated with a reported 49 fatalities on both sides of the conflict. The graph below depicts the decline in violence since the start of 2018.

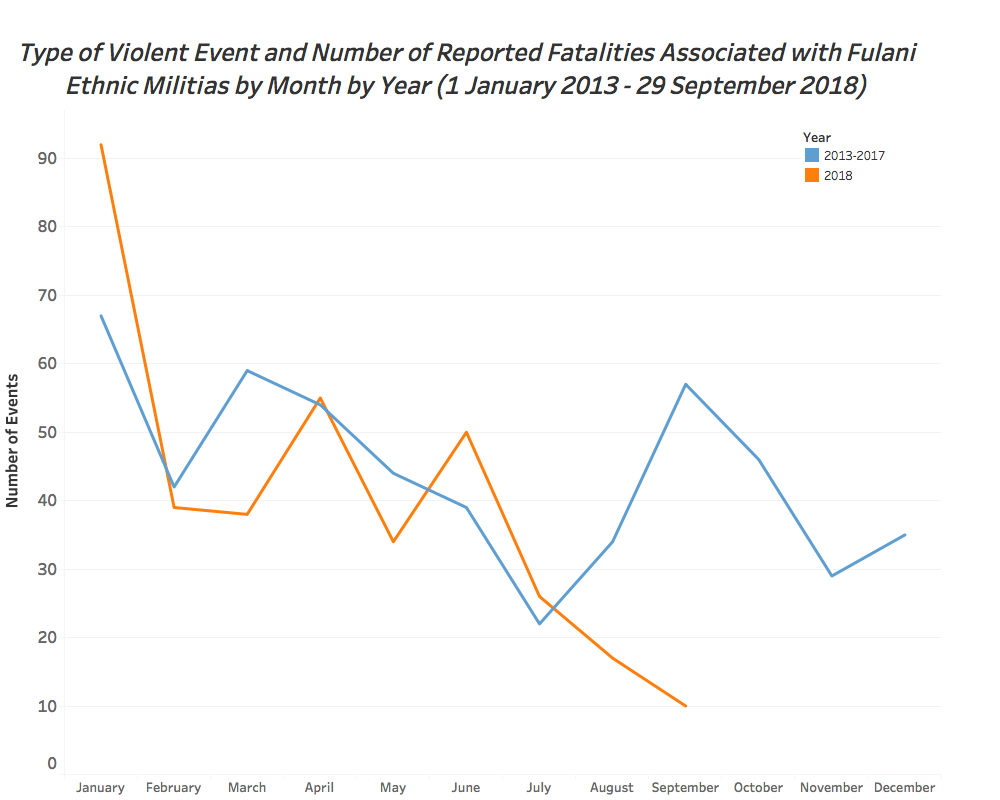

Part of this decline is seasonal. As depicted in the graph below, violence involving Fulani militias typically begins to decline in the late summer into the early fall, corresponding with the rainy season, when large-scale movement is difficult and during an important season for livelihoods production (World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal). Even if trends do not shift upwards again with the next dry season, long-term trends suggest that violence associated with conflicts between Fulani herdsmen and farmers throughout the country will continue well into the future as they have prior to the spike earlier this year for quite some time.

Importantly, however, shifts in the type of violent activity associated with Fulani herdsmen in 2018 thus far suggest that violence may be shifting away from intercommunal violence towards confrontations with the government and the targeting of civilians. Examining the patterns of violence associated with Fulani militias over the past five years helps to contextualize what is novel about the Fulani-herdsman related violence in 2018 as compared to previous years .

What’s Different About Fulani Militia violence in 2018?

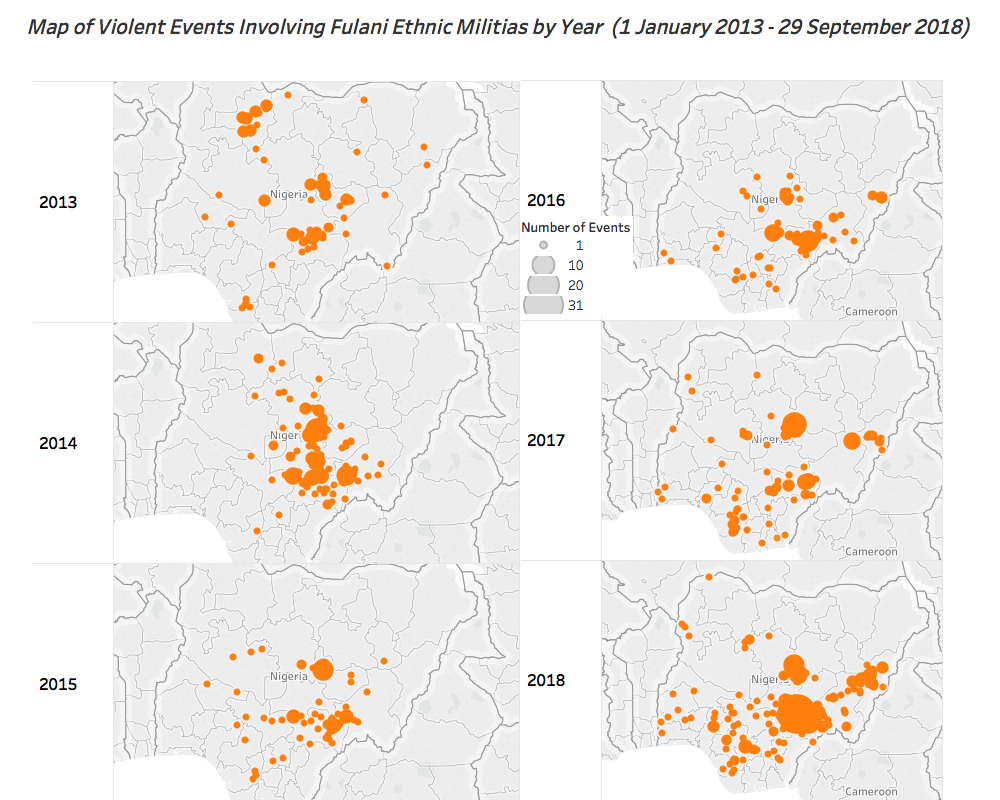

Much of the uptick in the overall levels of the violence involving Fulani militias in 2018 can be attributed to dramatic increases in a handful of states. Between 2017 and 2018, the number of violent events involving Fulani militias increased from 26 to 100 in Benue State, from 20 to 69 in Plateau State, from 8 to 43 in Taraba State, and from 1 to 40 in Nassarawa. All of these states are in the country’s “Middle Belt,” located in the In addition to increased violence in these states, in 2018 violence spread to areas that had not been affected by violent events involving Fulani militias since 2013. The figure below illustrates this southward trend of violence associated with Fulani militias over the past five years. Part of this movement may be attributable to the violence in the country’s North East, which has made some communities too dangerous to reside in. Relatedly, the Boko Haram conflict has drawn the security sector’s attention to the North East, leaving fewer resources to respond to instability elsewhere.

More fundamentally, changes in land use, resulting from things like drought and displacement, have created a breakdown in customary relationships in a number of communities throughout Nigeria. The role of land use, and land use ‘winners and losers’ from legislation, cannot be overstated. In previous periods, any ‘herder’ movement was arranged by customary authorities with more settled communities. This was contingent on the ability of customary authorities to regulate land use. Those powers were mitigated by legislation, and by increasing farming settlements. Few arrangements have been made for pastoral communities across Nigeria and elsewhere, leading to extremely vulnerable and contentious livelihood choices.

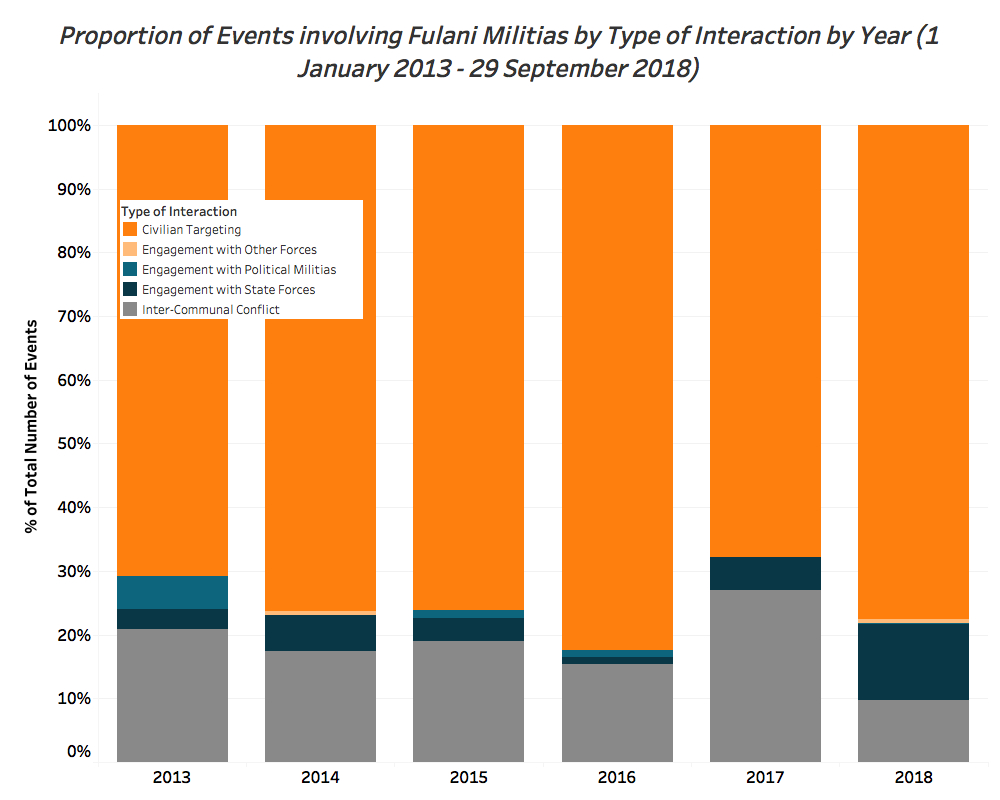

The geographic shift in where violence associated with Fulani militias occurs has been accompanied by a change in targeting patterns. As demonstrated by below, the proportion of violence involving Fulani militias has, since 2013, shifted towards violence against civilians and confrontations with the government and away from intercommunal violence. In 2013, 21% of violent events associated with Fulani militants were fights with other communal militias; this fell to just under 10% of attacks in 2018 thus far. In contrast, the proportion of events that have involved violence targeting civilians by Fulani militia rose from less than 71% of events in 2013 to over 77% in 2018; this nearly 6% jump coincided with a significant increase in the activity level of Fulani militias, meaning that it constitutes a significant change in the security of civilians in affected areas. In 2018, Fulani militants have also begun to use remote violence, a notable development that may portend a fundamental shift in conflict dynamics.

Additionally, there has been a shift towards violent confrontations with the government. In 2013, such interactions constituted around 3% of the violent events associated with Fulani militias; in 2018, that proportion has risen to nearly 12%. Part of this increase may be attributable to the measures that the government has taken in response to the crisis. In 2018, the government has “deployed additional police and army units and launched two military operations to curb violence in six states – Exercise Cat Race… and subsequently Operation Whirl Stroke” in the states hardest hit by the crisis (International Crisis Group, 26 July 2018). According to the Nigerian Acting Director for Defence Information, Operation Whirl stroke “is different from normal military operations because it has drawn Special forces from all security agencies,” suggesting that the government is bringing more pressure to bear on the crisis than previously (The Guardian, 19 May 2018).

What Might be Next?

Some government policies that have been adopted in recent years in response to the crisis threaten to incentivize future conflict. For example, Benue State passed legislation related to open grazing in November 2017 that has served to inflame tensions in the state. The reform outlaws grazing outside of ranches and legislates that livestock only be moved by rail or road (International Crisis Group, 26 July 2018). Unsurprisingly, Fulani herdsmen complain that it is discriminatory, while residents support the law as a corrective to the federal government’s perceived lax response to the crisis (International Crisis Group, 26 July 2018). Though Buhari’s administration has overseen both Exercise Cat Race and Operation Whirl Stroke, there is a widely held perception that Buhari (who is ethnically Fulani) is biased in favor of the Fulani militias (CTC Sentinel, February 2017).

The possibility of violence increasing to January 2018 levels in January 2019 remains a possibility, particularly given the impending February 2019 elections, in which incumbent President Buhari is seeking re-election. The campaign season may see the violence take on partisan characteristics, if campaigns work to associate Fulani militias with Buhari’s All Progressives Congress (APC). This dynamic is already at play in Ekiti State, where the State Publicity Secretary of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), Jackson Adebayo, released a statement characterized the APC as encouraging Fulani militias to engage in violence. The statement, released in February 2018, said that “Rather than condemning the herdsmen killings… what the APC and its obviously heartless leaders have been doing is to criticize Governor Fayose for the anti-grazing law and visiting Benue State to commiserate with Governor Samuel Ortom and the people of the State over the killings of 73 people by herdsmen” (Daily Post, 12 February 2018). This sort of purposeful misrepresentation and baiting, likely to increase as the election approaches, could contribute to an escalation of violence involving Fulani militias.

Though violence involving Fulani militias appears to be on the decline now, the shifts in the targets and type of violence — combined with the failure of the government to address some of the underlying structural incentives that have fostered this conflict, and the risk of the politicization of this violence — suggest that this decline may largely be seasonal and that violence may accelerate in early 2019.