Five years after the violent elections of 2013, general elections were held again in Pakistan on 25 July 2018. The election process itself was tainted with less violence and less interference from militants like the Pakistani Taliban (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece). However, with 30 seats at the national and provincial level still unfilled either because they were vacated or because voting was postponed, Pakistan’s election season is not over yet. Vacant seats will be filled in by-elections scheduled for mid- and late-October (The Express Tribune, August 17, 2018). While campaigning and electioneering have continued in several provinces, so has electoral violence in the form of targeted attacks against candidates and members of political parties.

A relatively new party, Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI), won the most seats in the July 2018 general elections in a major upset. Political gains made by PTI led to changes in the political power dynamics in Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces. While the majority of the vacant seats up for election are in Punjab province, the majority of targeted political violence has been reported in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh provinces thus far. Recent political violence in the lead up to the by-elections is indicative of the high levels of political tension and competition in Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces, caused in part by significant changes in political support in these areas during the 2018 general elections. As political competition ramps up in Punjab, we might expect a similar outcome.

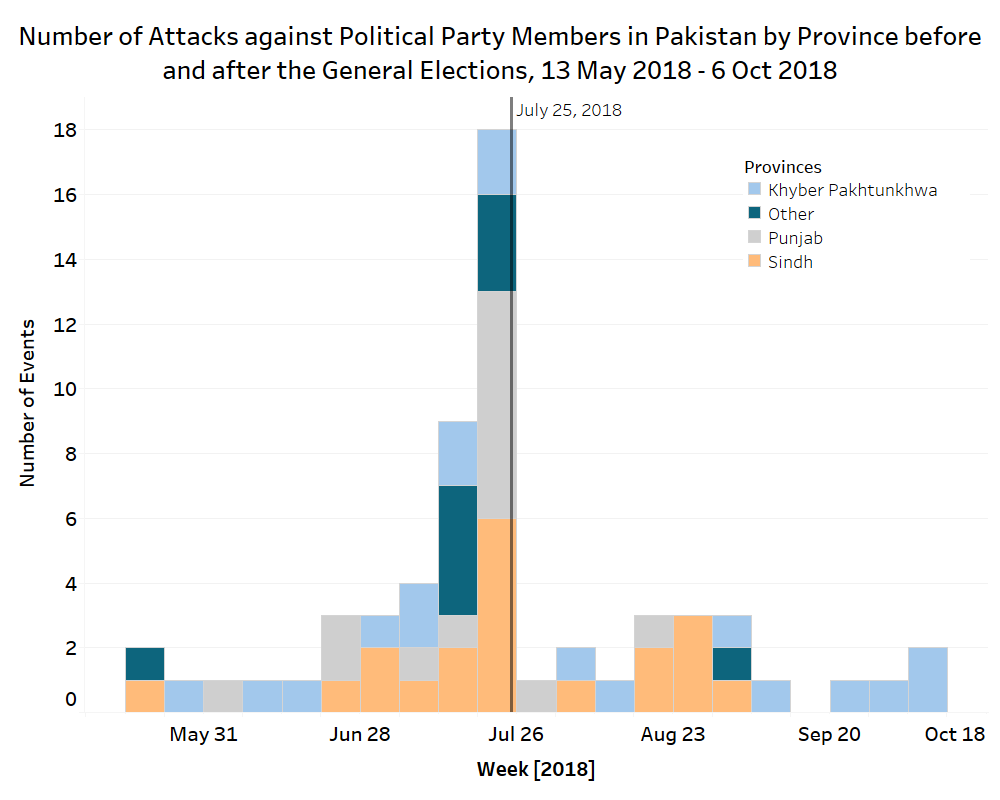

The graph below shows the number of reported attacks against party affiliates, leaders, and candidates each week in the ten weeks prior to and following the general elections on 25 July. There was a significant spike in targeted violence in the two weeks prior to election day, with 18 attacks during the election week itself. Three of these were against PTI members in Punjab province, while four attacks victimized PPP affiliates in Sindh province. Just over one third of these eighteen attacks were in Punjab.

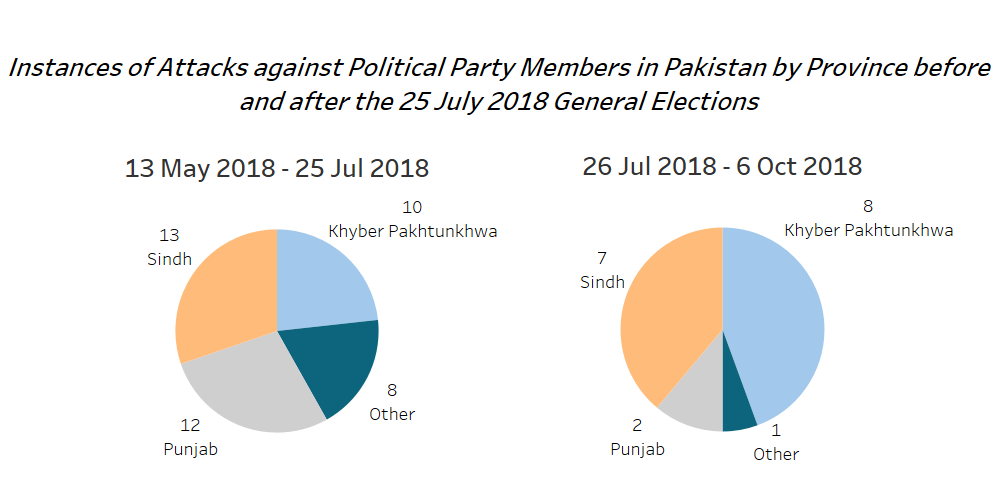

Targeted attacks dropped significantly after the general elections and returned to levels seen about three weeks prior to 25 July. Noticeably, very few attacks have occurred in Punjab or other provinces after the general elections, despite the fact that several instances of violence were reported in these areas in the weeks prior to 25 July. The figure below illustrates the difference in proportions of attacks by province before and after the July elections–depicting the stark increase in the proportion of violence occurring in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (blue) and Sindh (orange) and the decrease in Punjab (gray). This difference before and after the general elections suggests that, so far, the upcoming by-elections are causing less political tension or competition in Punjab relative to the neighboring provinces of Sindh and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where violent trends continue.

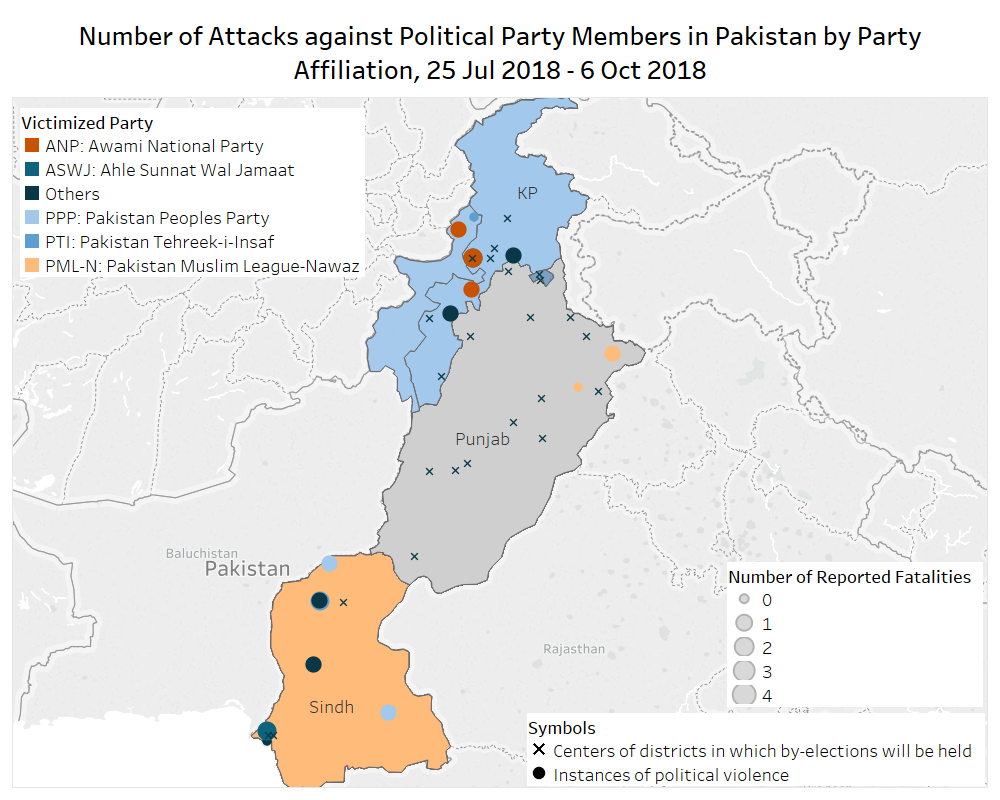

The map below shows the locations of the upcoming by-elections as well as reported targeted attacks and killings of party leaders, workers, and by-election candidates in the ten weeks since the 25 July general elections. Seven constituencies in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in blue on the map, will vote in October. Political violence is more common in this area due to limited governance, tribal factions, and the infiltration of militant groups from across the porous border with Afghanistan. In contrast, almost no militant violence is reported in Sindh province, in orange. Tribal groups, however, play a prominent role in Sindh’s political landscape and high levels of dissatisfaction by the local populations–over issues such as corruption or the government’s failure to provide basic amenities, such as water and electricity–lead to frequent demonstrations in the province. Three districts in Sindh will vote in the by-elections. Although there are few pending elections, five out of every six incidents of targeted violence were reported in these two provinces since 25 July. Eight party affiliates have been killed over the past ten weeks in eight separate attacks in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa; the same number have been killed in Sindh in this time period.

Sindh province (in orange on the map above) has previously served as the political base for the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). However, representatives of PTI won in a number of constituencies–particularly along the coast–in the July election. The election of a PTI candidate for Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city and the capital of Sindh province, was a major upset, given the city’s longstanding allegiance to the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) (Al Jazeera, July 28, 2018). Since 25 July, members of minor parties, Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) and Pakistan Muslim League-Functional (PML-F), have been attacked twice in Karachi by unidentified gunmen. ASWJ had publicly backed PTI in the July elections, while PML-F was part of an anti-PPP coalition (The Express Tribune, August 4, 2018; Dawn, July 30, 2018). On the opposing side, PPP workers were attacked in Umerkot district by unidentified assailants and in Jacobabad district by PTI workers in August, highlighting their vulnerability and simmering antagonism against the former political elite in the province.

The July general elections also led to major changes in the political landscape of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (in blue on the map above).[1] PTI dominated the election and won nearly every National Assembly seat in the province. This is in stark contrast to the province’s political landscape prior to the 2013 elections, when the Awami National Party (ANP) and PPP controlled most of the area. Between 2013 and 2018, PTI began to creep onto the scene in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and won a number of seats; the rest were split among minor parties (Al Jazeera, 2018). ANP and other religiously-motivated, nationalist, and rightist parties remain highly politically active in the province despite having very little national representation. The PTI landslide win–despite the campaigning efforts of other parties like ANP and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-Fazal (JUI-F), as well as strong grassroot support for the former–resulted in the boiling over of political tension into political violence in advance of the by-elections. In September and October, six targeted attacks by unidentified attackers against political affiliates were reported from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, with PTI, ANP, PPP, ASWJ, and others falling victim to violence. As just one example of a clear targeted killing in the area shows, a by-election candidate of minor party ASWJ and his bodyguard were shot dead in the province’s capital, Peshawar, on 4 October.

Meanwhile, 14 different constituencies in Punjab (in gray on the map above) will vote in the by-elections, but these areas so far have been largely devoid of the same political violence seen in its neighboring provinces. In Punjab province, PTI managed to win over many constituencies which had been under the control of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) prior to 25 July. “Hawa,” or the expectation of how politics will go, may have helped PTI gain momentum. Once people believed that PML-N had lost the political power needed to win a national or provincial majority, they recalculated their support (Herald, July 24, 2018). One reason for the lack of confidence in PML-N was that its contentious history with another major party, PPP, left it without much external support (The Daily Times, October 5, 2018). Not only did PML-N candidates abandon their party and either rebrand themselves as PTI members or contest as independents, but also some independents and other parties threw their support behind PTI. This added to the widening gap in between PTI and PML-N that was apparent in the aftermath of 25 July (Herald, July 24, 2018; The Nation, October 9, 2018).

With the by-elections approaching shortly, however, this calculus may be different. In a significant change of heart, PPP is now open to the idea of supporting PML-N against their common enemy, PTI (The Nation, October 9, 2018). The addition of PPP’s support to the former forerunner in the Punjab Assembly makes it more difficult to predict the outcome of the by-elections, making it a much tighter race. This increased competition between PTI and PML-N may result in more violence in the days leading up to voting and in the aftermath.

While the overall levels of reported violence in Punjab remained low following the general election back in July, there were two instances in which tensions between these two major parties emerged following the elections. PTI workers attacked PML-N supporters in two areas in which elections were held on 25 July as a direct result of the election results. In Kasur, a PTI candidate won a national seat with only 24 more votes than a PML-N candidate (Result.pk, 2018). The election in Pasrur was also close; a PML-N representative beat a PTI candidate by less than two percent of votes (Result.pk, 2018). The outcomes of the upcoming elections in Punjab will help PTI to cement its newfound power in the province or will help opposition parties, such as PML-N, to stake their claim over some of the most populous areas of the country. Given tensions between the PML-N and PTI following the close results of the July elections, with competition becoming closer in the lead up to this month’s by-elections, violence is not out of the question.

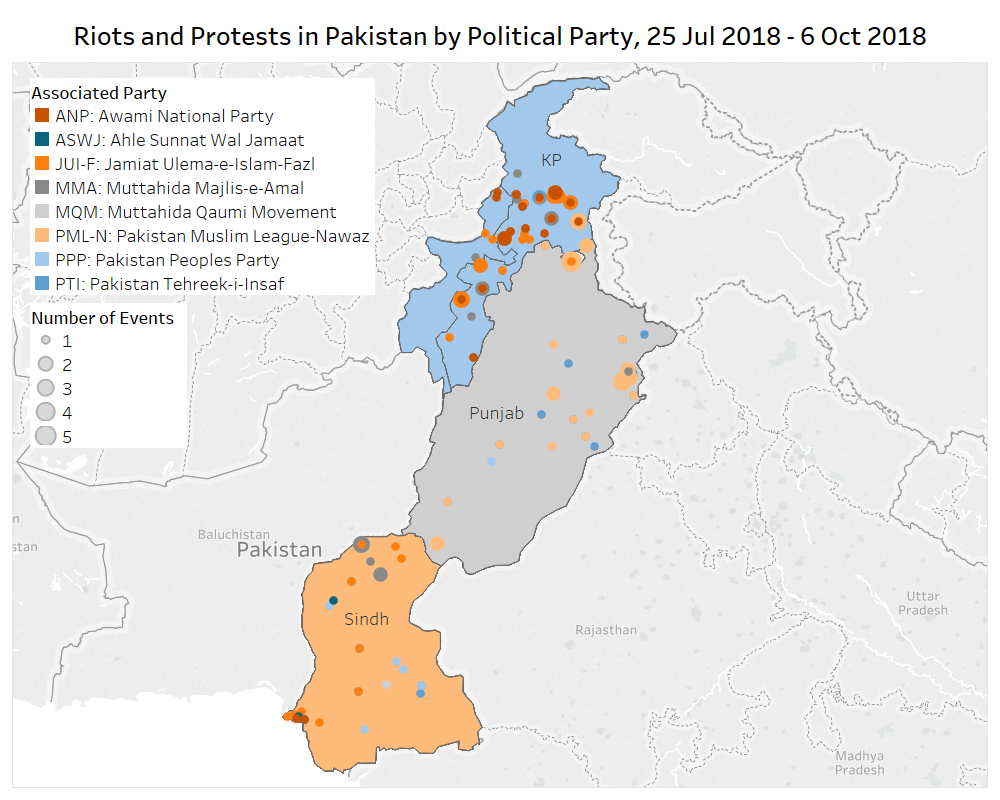

Besides looking at incidents of targeted political violence, trends in demonstrations organised by political parties further illustrate the differences in political activism among the three provinces. The map below shows protests or riots organized and attended only by a single political party since the general elections in July.[2] Punjab is home to over half of Pakistan’s population, yet relatively little political activism is reported there. Instead, the concentration of activity in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh shows the extent to which politics and parties matter in these provinces and helps point to why political violence is occurring more in these areas. The fact that the residents of these areas so often mobilize as party activists or workers compared to Punjabis indicates that changes in parties, or the potential thereof in the upcoming elections, may have greater implications in their day-to-day lives or may further inflame long-standing grievances with local and national governments. The extent to which dynamics may change in Punjab in the lead up to the by-elections given recent events remains to be seen.

As PTI ushers in the promised “Naya Pakistan”–a new Pakistan free of corruption–with its newfound political power, certain provinces in the country are grappling with the unrest that accompanies major political change. It is likely that political violence and unrest in these areas will continue leading up to and following the by-elections; the political tension in Sindh, Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa runs deeper than the handful of seats being contested in October.

[1] In addition to the change of political dominance in the province, the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) were merged with neighbouring province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in May 2018. While some targeted attacks were reported from the former FATA territory in the weeks after 25 July, the vast majority of the attacks were recorded in the area that originally constituted Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

[2] While political party activists participated in other riots and protests–either across party lines or with other groups, such as farmers and labourers–during this time, the data represented in the map only account for the riots and protests in which a single political party was the only associated actor. The events in which only one party was present are the best proxy measure for a party’s ability to mobilize based solely on party identity and point to the importance of a party as a legitimate means of voicing dissatisfaction and seeking redress for political grievances. Parties are present in all parts of the country, but the different levels of rioting and protesting as a party in different areas highlights the varying strength and importance of those parties as political vessels.