The North Kivu province is the site of a disproportionate share of the violent events and protests in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In 2018 thus far, 51% of violent events and protests have taken place in the province. Since August, residents have also had to contend with another source of insecurity: an outbreak of the Ebola virus. The political dynamics of the North Kivu region have exacerbated the Ebola crisis. Not only is the crisis response impeded by the activity of armed groups, residents’ lack of trust in the government has put humanitarian aid workers in danger and has made it difficult to implement public health measures.

Since August, when the outbreak was first detected, there have been more than 200 cases, which have resulted in 135 deaths thus far (World Health Organization, October 2018). The persistent insecurity in the region has hamstrung the response. As of October 12, 7 of the 236 safe burials could not be completed because of security conditions (Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, 12 October 2018). In addition to the ambient insecurity, medical teams have also been the targets of violence; some of the international Ebola response teams have had to suspend activities in the region. The Congolese government has deployed the security sector to “protect teams transporting the bodies of Ebola victims for burial”, though, given the community’s frustration with the government, it is unclear how effective this protection will be (Al Jazeera, 10 October 2018).

Understanding the dynamics of violence (from both the government and rebel groups active in North Kivu) is critical for designing and implementing a more effective response to the virus. This analysis will examine how the dynamics of violence have shaped the environment with which the Ebola response must contend. This article will compare the dynamics of violence and protest in 2018 to 2017 in North Kivu, and will assess what has changed in the region in the 2.5 months since the outbreak was detected.

Violence in North Kivu

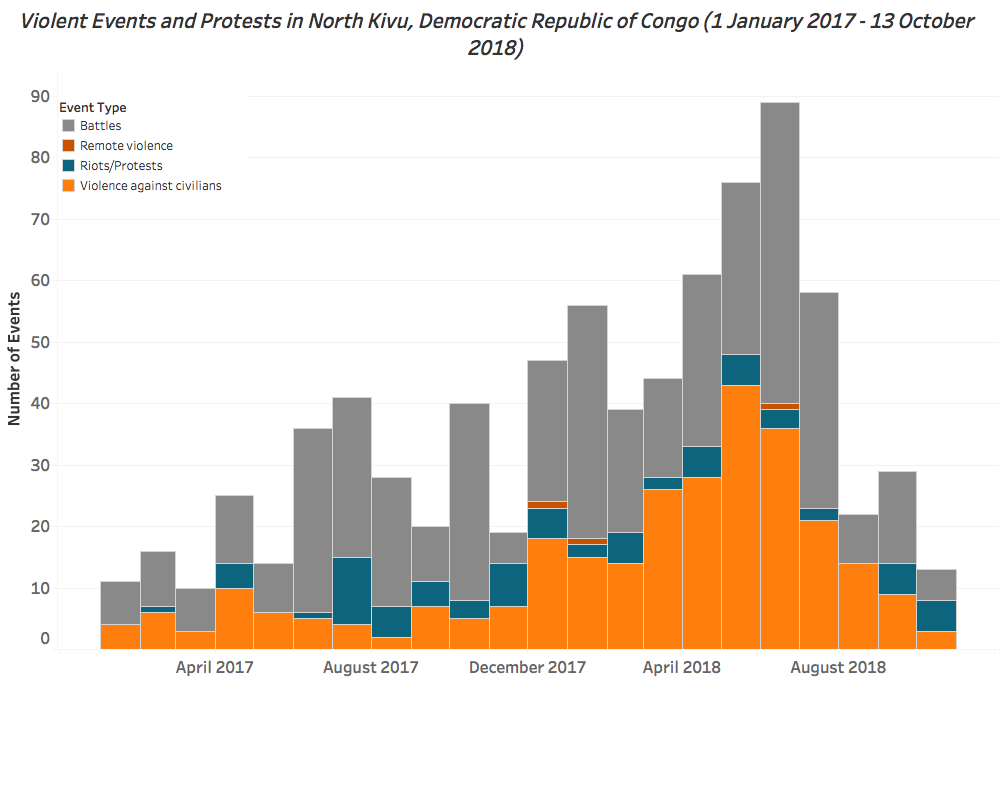

The number of violent events in North Kivu in 2018 thus far has surpassed the number of violent events recorded for all of 2017. In 2017 there were 307 violent events and protests recorded in the province, resulting in 795 reported fatalities; in 2018 to date, there have been 493 violent events and protests, responsible for 801 reported fatalities. Much of the increase in violence in 2018 is driven by an increase in the targeting of civilians by rebel groups and community militias, as well as battles between armed groups and the government, as demonstrated in the graph below.

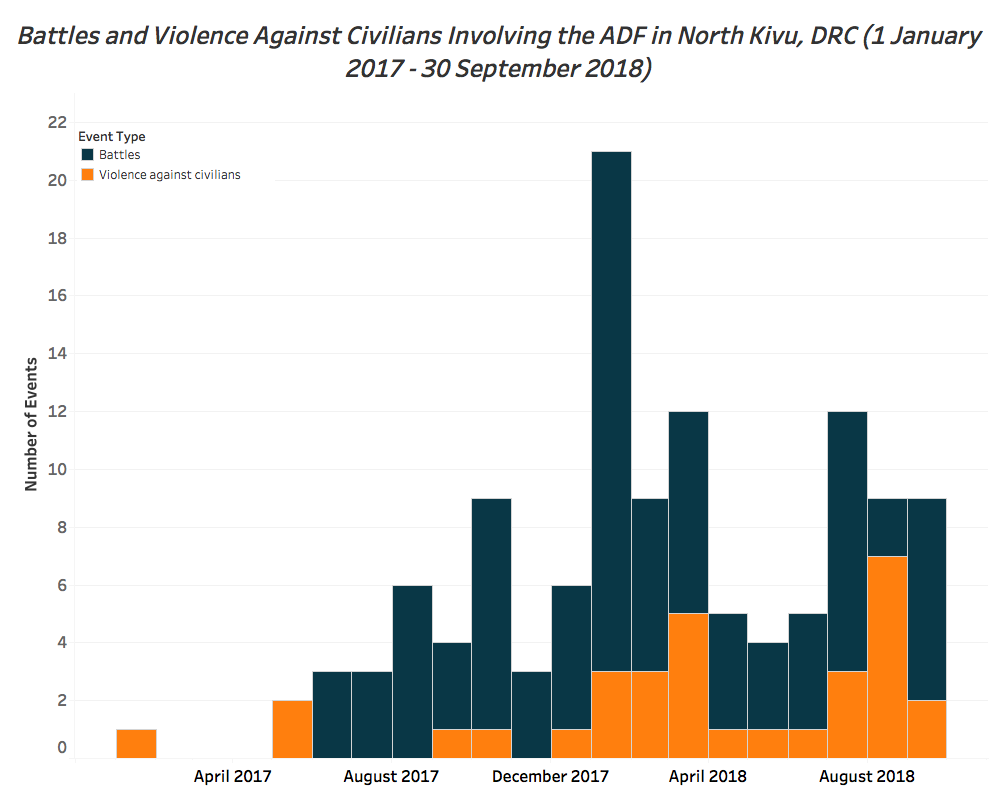

Despite the difficulties in tracking ADF activities, recorded events suggest that the group is becoming more active in 2018. Violent events involving the ADF in North Kivu have surged more than 140% from 2017, rising to 92 violent events in 2018 thus far. The government’s offensive may be behind the increased number of activities involving the rebel group, as well as behind the increase in civilian targeting by rebel groups. Research suggests that rebels engage in violence against civilians when they are an accessible population and as a means of opening new fronts in the conflict (Raleigh, 2012).

The government’s efforts to quell the insurgency have altered the dynamics of violence in the province. As demonstrated below, however, the government has not been able to put an end to the ADF’s activities. Despite a dip in activities from April 2018 – June 2018, there was a surge in ADF activity in July 2018 and a significant increase in civilian targeting by the group in August 2018 (see graph below).

In 2017, there were 10 instances of rebel groups (including the ADF) targeting civilians in North Kivu and 49 instances of political militias targeting civilians; in 2018, these numbers have risen to 47 and 133, respectively. A significant proportion of the increase in civilian targeting can in large part be attributed to the increase in the activities by unidentified armed groups, which rose from 20 events in 2017 to 98 in 2018. The reason for this surge in civilian targeting generally may be inter-militia competition and signalling of their relative strength (Wood and Kathman, 2015).

The Congolese security forces have also targeted civilians in North Kivu in 2018. This year, there have been 17 events in which the Congolese security sector targeted civilians, resulting in a reported 19 fatalities. This increase in civilian targeting may be a function of the difficulty of discerning civilians from rebel group members; according to the Congo Research Group, though the ADF was not founded in the Democratic Republic of Congo, it has cultivated significant ties with the local community and pursued integrative strategies (Congo Research Group, September 2017).

Given the overall surge in violence against civilians, the military offensive has done little to endear the Congolese government to the local population. On April 25, civil society members organized a peaceful protest, attended by hundreds, against the persistent insecurity; the police used tear gas to disperse the protests and arrested 42 of the attendees.

It was within this contentious security atmosphere that the latest outbreak of Ebola emerged in North Kivu in August 2018. Beni, a district identified as a hotspot for conflict in the province since April 2018, is one of the communities most affected by the outbreak.

Insecurity and the Ebola Response

Though the number of violent events and protests have declined precipitously from their summer highs, the public health response to the Ebola outbreak has still been hamstrung by security concerns. Those tasked with responding to the outbreak must grapple with both the general insecurity resulting from the ongoing violence in North Kivu, as well as with attacks directed against them by armed groups and frustrated and mistrustful residents.

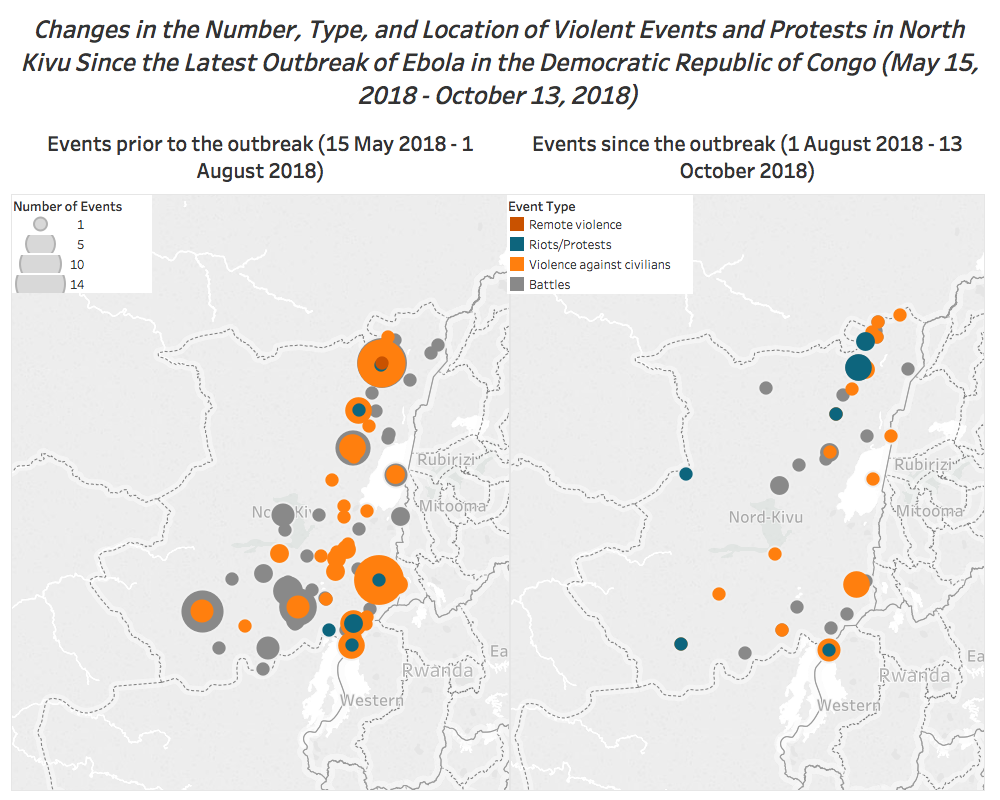

As demonstrated in the maps below, in the 2.5 months since the outbreak, violent events and protests in the province have declined in the center of the province, while there has been an increase of protest activity in the northeastern corner.

In late September, nearly all of the efforts to respond to the outbreak in Beni were put on hold after an armed group launched an attack on the town (Oxfam, 3 October 2018). As previously discussed, insecurity has made it impossible for aid workers to access certain communities, facilitating the spread of the virus. According to the World Health Organization’s emergency response chief, Peter Salama, one of the most difficult challenges that the Ebola response teams face is the spread of cases to “red zones” considered to be too dangerous for health responders to access (Vox, 10 October 2018).

In addition to the insecurity, a number of international public health responses have cited “community resistance” as a potent challenge to the Ebola response (Oxfam, 3 October 2018). This community resistance is distinct from the violence or threat of violence that aid workers face from armed groups operating in the communities. According to Oxfam, community members block roads, throw stones, and destroy community centers, “delaying all aspects of the response safe burials, contact tracing – and reducing its effectiveness” (Oxfam, 3 October 2018). As of October 12, more than 13% of the safe burials “were unsuccessful because of community refusal or burials conducted before the teams arrived” (Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, 12 October 2018).

Civil society in Beni called for a general strike in the town and demanded that the Ebola response come to a halt. In Beni and elsewhere throughout the region, there is a sense of frustration that only Ebola marshalls such a robust response and a deep skepticism about the state and international community’s commitment to their welfare (Oxfam, 3 October 2018).

Conclusion

Communities in North Kivu face potent threats to their security, both from on-going violence involving armed groups and the government, but also now from a new Ebola outbreak. This is particularly the case for those living in Beni, which is dually burdened with approximately 40% of the violent events involving the ADF in North Kivu and approximately 66% of the Ebola cases reported to the WHO since September (World Health Organization, 9 October 2018).

These two crises do not operate distinctly from one another, however. The government’s inability to provide security to communities in these regions, and the outright targeting of civilians by the state’s security sector, have eroded communities’ trust in the state. This perceived illegitimacy of the state makes it more difficult for the international community to contain the outbreak of Ebola. The characterization of this outbreak of Ebola as being the “perfect storm” obscures the fact that, while the government cannot be faulted for the latest outbreak of Ebola, failures of governance have facilitated the spread of the disease.