Over 6500 political violence, protests, and other non-violent events for the years 2010 to 2012 have been added to ACLED’s Bangladesh dataset. The coverage period of ACLED’s Bangladesh dataset now spans from 2010 to present, and the dataset as a whole now contains around 13800 events. With the addition of the new data, we can take a more detailed look at Bangladesh’s conflict environment in recent years.

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh, one of the most densely populated regions of the world, receives very little international news coverage compared to its more prominent neighbors, especially Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. However, Bangladesh’s low international media profile hides an extremely violent and deadly conflict landscape that is marked by entrenched political bipartisanism rooted in the historic rivalries between the two major political parties – the secular, socialist Awami League (AL) and the nationalist National Party (BNP) with its Islamic orientation.

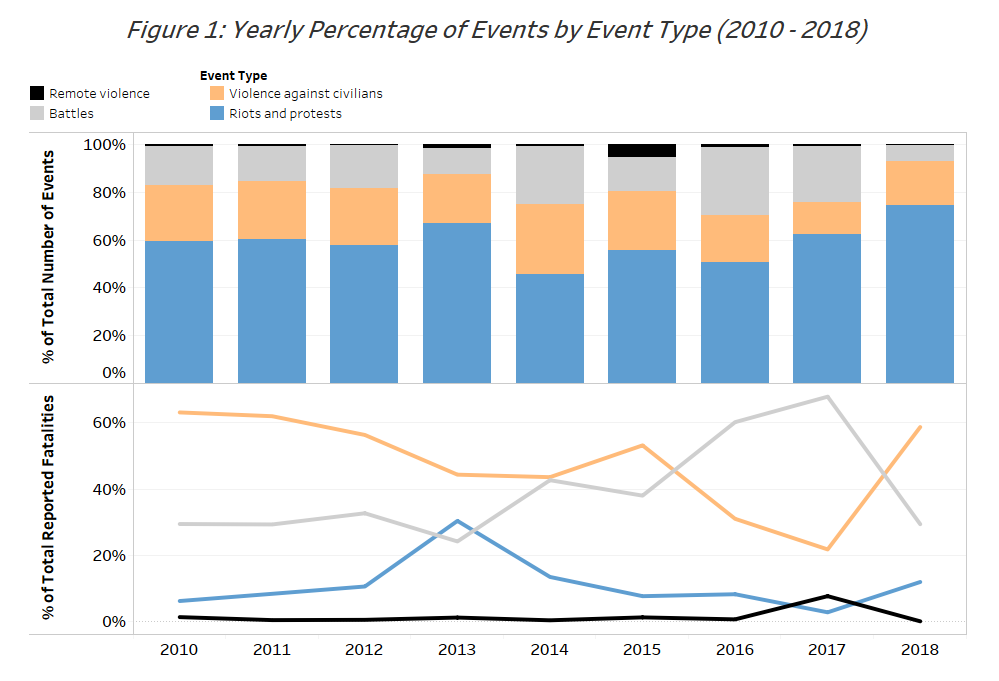

ACLED classifies event types by organized violence – including battles, remote violence and violence against civilians – and demonstration events — which include peaceful protests and violent riots. Much like in other South Asian countries (with the exception of Afghanistan), demonstrations are the most frequently reported event type in Bangladesh; followed by attacks against civilians, battles, and remote violence. The figure below shows that conflict dynamics remained largely static from 2010 to 2018; the proportion of events in Bangladesh that are violent attacks on civilians (in orange) – and, to a lesser extent, battles (in gray) – increased relative to demonstrations (in blue) in 2014, the year of the last general election in Bangladesh. The proportion of events involving remote violence (in black) remains low for all years, with a significant spike in 2015, meaning that in 2015, remote violence made up a larger-than-usual proportion of all events in Bangladesh. This relative increase is likely linked to increased tensions and violent clashes between AL and BNP activists in the first few months of that year, following the decision by the ruling AL government to confine BNP leader and former prime minister, Khaleda Zia (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece). For the most part, with the exception of 2016 and 2017, targeted attacks on civilians have made up the highest proportion of reported fatalities in the country.

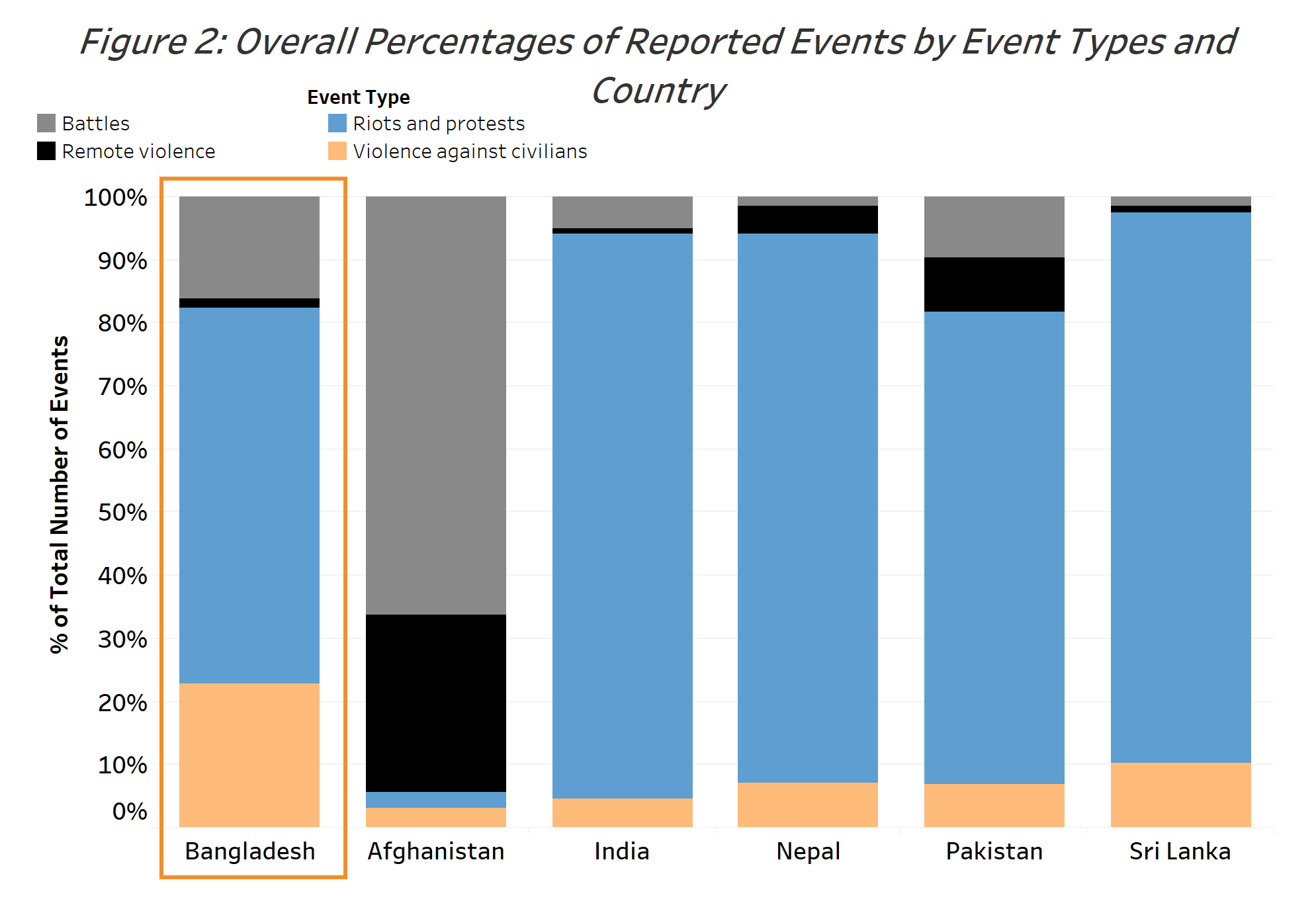

Comparing South Asian countries highlights that the conflict environment in Bangladesh is highly volatile. The figure below demonstrates that, relative to the overall number of reported events per country, targeted attacks against civilians (in orange) make up a much larger proportion of the conflict landscape in Bangladesh relative to other South Asian countries. With the exception of Afghanistan, which is the scene of an ongoing military conflict with Islamist groups, the relative proportion of battle events (in gray) is also higher in Bangladesh than in other South Asian countries.

These numbers are striking given that Bangladeshi state forces have not been engaged in any major military conflicts with domestic or foreign adversaries during the time period in question. This leads to the question, what kind of violent engagements are dominating the Bangladeshi conflict landscape?

The vast majority of engagements in Bangladesh involve unarmed, or crudely armed, political violence (rioting) and political militia violence. While rioting makes up the largest proportion of events in Bangladesh, the relative proportion of reported fatalities resulting from these events is lower, given they involve actors who are unarmed or crudely armed.

Since Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the political landscape has been marked by strong bipartisanism and deep rooted rivalries between the two major parties, Awami League (AL) and National Party (BNP). Both parties have a vast organizational structure and are deeply entrenched into Bangladeshi society through front organizations including youth and student clubs, female wings, and labour unions.

Both, AL and BNP have also formed alliances with other minor parties. AL is leading the ruling coalition of the Grand Alliance which was formed in 2008. BNP and other opposition parties formed the 18 Party Alliance in 2012, replacing the older Four Party Alliance. Besides the leading BNP and its front organisations, Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and its student organisation Islami Chhatra Shibir (ICS) are among the most active actors in the 18 Party Alliance.

Deep faultlines between the two major blocks have led to an environment of toxic political enmity which frequently results in violence. Just in October 2018, at least 38 people died in Bangladesh due to organized violence, 20 of them were political activists either killed during clashes or in targeted attacks.

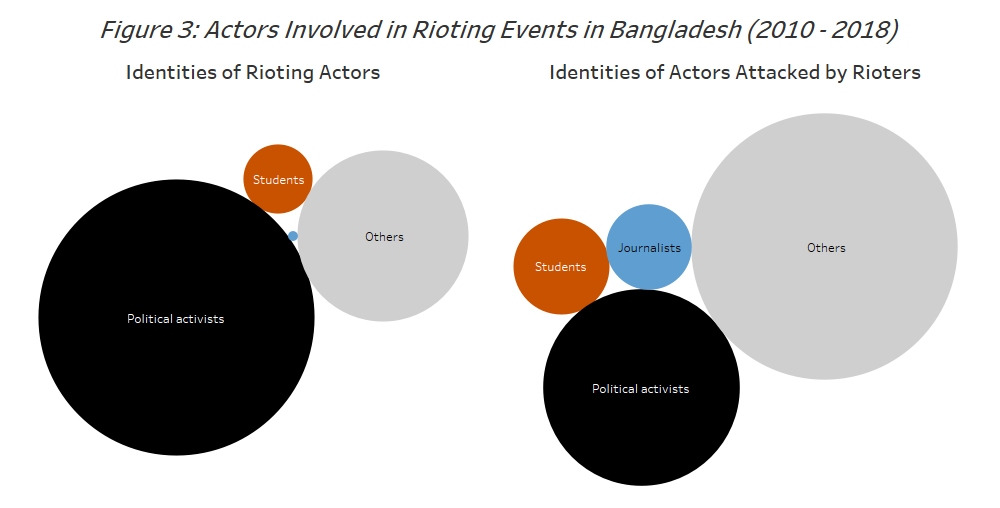

Looking at the driving force behind unarmed or crudely armed political violence in Bangladesh, the figure below points to how political parties make up the vast majority of actors engaged in rioting. With regard to the victims of rioting, non-political groups (classified as “other”, in gray) are the ones most affected by unarmed or crudely armed political violence. This group of victims is typically made up of civilian bystanders who are either targeted by rioters or seen as collateral damage during rioting. Political activists – including front organizations (in black) – make up the second largest group of actors affected by unarmed or crudely armed political violence, followed by independent student groups (in brown) who do not have an affiliation to a political party. With students being a very active protest group in Bangladesh, student protests are often attacked by student wings of political parties. Only recently, during the end of July and beginning of August, members of the ruling AL and its student wing, the Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), assaulted students protesting for greater road safety (BBC, 04 August 2018). Journalists (in blue) are often attacked by rioters as well due to their reporting on those events.

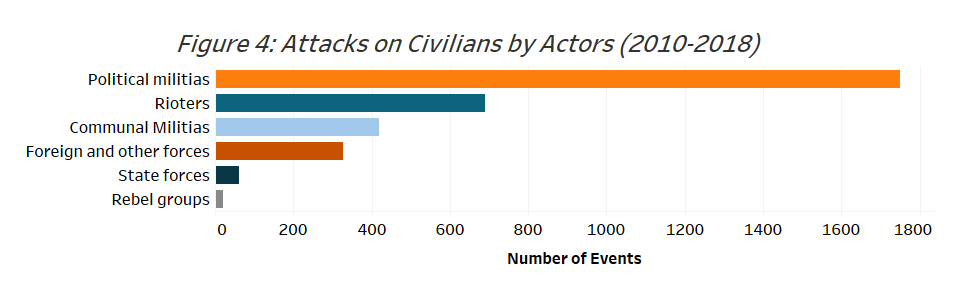

Engagements involving armed political militias and unidentified armed groups, while making up a lower proportion of total events, result in the highest proportion of reported fatalities (60%) compared to all other forms of violent engagement. These actors are also the main agents perpetrating attacks against civilians (see figure below).

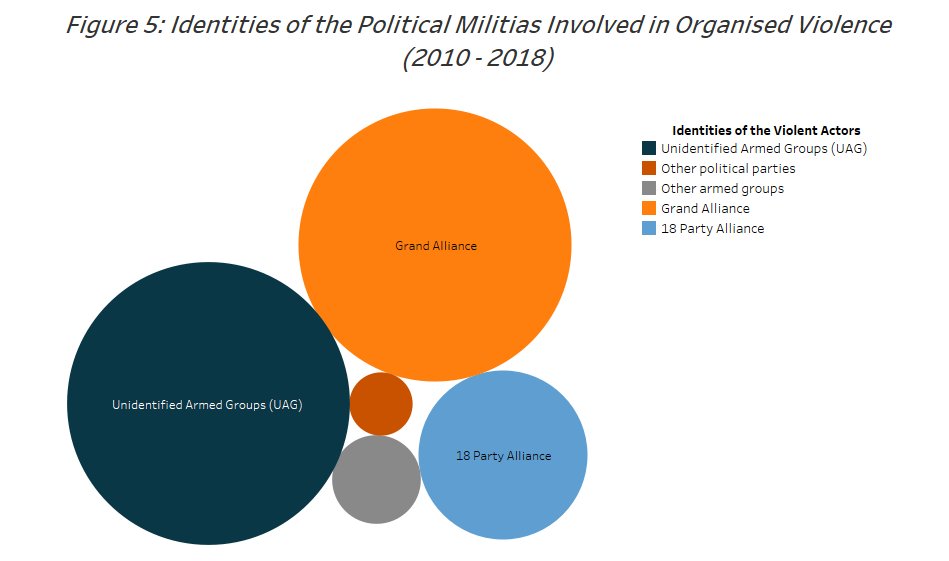

With regard to political militia violence, Figure 5 below depicts the identities of the political militias involved in armed violence. The numbers based on recorded events suggest that the ruling AL-led Grand Alliance (in orange) contributes significantly more to armed political violence than its political rival, the BNP-led 18 Party Alliance (in blue). In many cases, the identities of the attackers are not reported and these actors are labelled as Unidentified Armed Groups (UAG) in the data (in navy in the chart below). Attacks carried out by UAGs constitute a large share of the overall number of recorded events of political violence in Bangladesh. Keeping one’s identity anonymous lies in the interested of the attackers to avoid retributive measures by the attacked group or law enforcement. This arguably stands true for attacks on members of the ruling AL who wield significant influence over the state machinery, including the police force.

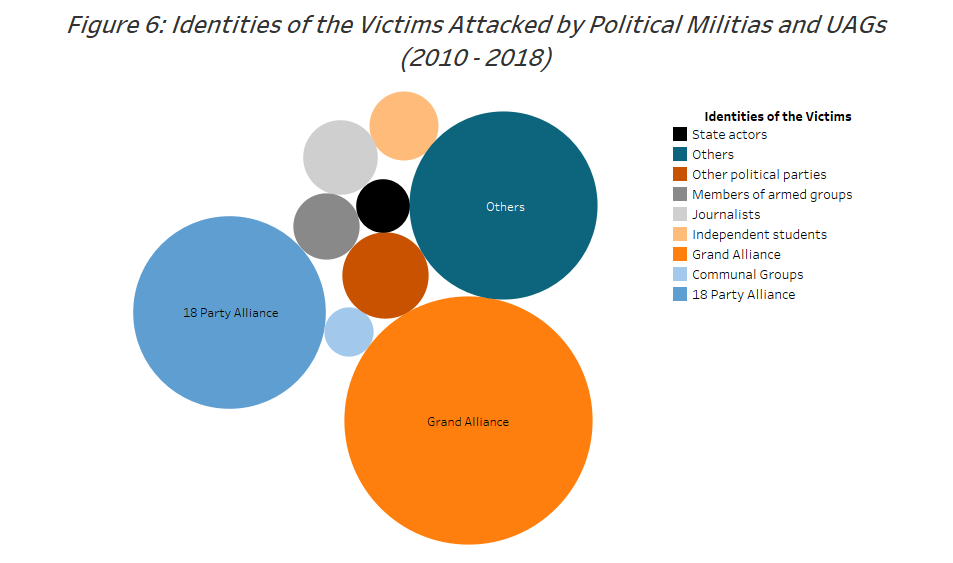

Figure 6 shows the identities of the victims of political militia violence. According to the data, while the Grand Alliance might contribute more to armed political violence than the 18 Party Alliance, members of the Grand Alliance also reportedly fall victim to political militia violence more than members of the 18 Party Alliance.

The figures above suggest that political parties, especially the Awami League and the Bangladesh National Party, are the driving force behind the majority of the conflict landscape in Bangladesh. Their political rivalry has created an environment in which both parties – along with unidentified armed groups – resort to vandalism, engage in violent clashes and target peaceful civilians.

With rioters and political militias contributing the largest share to the overall reported violence, Bangladesh’s conflict landscape is highly politicized and political parties are arguably the driving force behind the reported conflict events. However, other types of violence continue to coexist.

Communal violence contributes to a considerable share of violent events in Bangladesh. These forms of violent engagements rarely take place along the faultlines of religion or ethnicity, but instead are mainly motivated by livelihoods, such as access to resources or land. This type of violence accounts for the second highest proportion of reported fatalities this year.

Rebel violence against civilians or state forces makes up a relatively low proportion of all events in Bangladesh. A few radical Islamist groups are active in Bangladesh, most notably Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT). Both the Islamic State (IS) and Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) have claimed to be active in the country, which the Bangladesh government, however, denies (for more on this, see this past ACLED piece). The most well-known attack by Islamist groups is the attack on a café in Dhaka city on 1 July 2016 which reportedly left 28 people dead, including 20, mostly foreign, hostages (BBC, 2 July 2016).

State violence directed against protesters and civilians as well as violent interactions between other forces (foreign forces or private security forces) and domestic actors make up a relatively low proportion of total violence during all years in the dataset as well. These are predominantly a result of a consistent number of cross-border violent incidents along the international border with India and to a lesser extent along the international border with Myanmar. In the vast majority of the cases, the Indian Border Security Force shoots Bangladeshi civilians, mostly cattle traders, who try to cross the border.

The different manifestations of violence in Bangladesh have created a multidimensional and complex conflict environment which has been primarily dominated by violent political bipartisanism since the country’s independence in 1971. However, the complexity of disorder is constantly evolving and some argue that Bangladesh’s long history of two-party dominance hit a crossroads in 2018. Following the arrest and conviction of Khaleda Zia, chairman of the BNP, it remains to be seen whether a leaderless BNP can challenge the ruling AL (The Diplomat, 16 February 2018). General elections are scheduled for December 2018. This year – contrary to the 2014 elections which were boycotted by almost all the opposition parties and marred by large-scale violence and killings (Al Jazeera, 4 April 2018) – the BNP plans to contest in the elections. While the political future of the BNP and the two-party system remain to be seen, it is very unlikely that violence levels in Bangladesh will abate in the near future. A rise in the levels of political violence events has been recorded in Bangladesh in recent weeks and it is to be expected that this trend will continue until the election.